On-farm composting of cattle mortalities

As knackery and rendering services have declined in many parts of Victoria in recent years, the question of what to do with dead stock has become increasingly problematic for some farmers.

There are stringent guidelines for the burial of dead stock, see EPA Victoria Publication IWRG641 Farm Waste Management.

In some circumstances, farmers have been known to leave their animals in the ‘back paddock’ or even dump them in waterways. Dumping of farm animals in this manner is a biosecurity and environmental hazard – it is also illegal, and EPA Victoria has regulated non-compliant activities in the past.

Composting of dead farm animals is a relatively simple and effective process for the routine disposal of dead stock of all sizes (from poultry to mature cattle), but there are some risks that need to be managed.

Some farmers have been composting for a long time. The resulting compost can be applied to cultivated land, as top dressing on pastures, or on non-grazed farm areas such as shelterbelts.

Compost is a soil conditioner that is able to improve a range of different soil properties, such as organic matter content, and provide slow release nutrients.

Warning!

Where the cause of livestock illness or death is unknown or animals present with unusual disease symptoms, these cases should be investigated by a veterinarian to determine the cause and to exclude an emergency disease.

Suspicion of a notifiable disease including emergency diseases must be reported to an Agriculture Victoria Inspector of Livestock or a registered veterinarian. This can be through the all-hours Emergency Animal Disease Watch Hotline 1800 675 888.

If there is a suspicion that the animal may have died from an emergency disease, such as anthrax, the carcass must not be composted but disposed of under the direction of the Agriculture Victoria. If in doubt, a veterinarian should be contacted.

Phone the hotlineNote: Compost material resulting from animal carcasses is classified as ‘restricted animal material’ (RAM). Under the ruminant feed ban, it is illegal to feed RAM to ruminants or allow ruminants access to a stockpile of material containing RAM. Where compost containing RAM is spread as fertiliser on a pasture paddock used for grazing ruminant animals, the livestock should be kept out of the paddock until there has been sufficient pasture growth to absorb the compost. In good growing conditions, this grazing with-holding period is 21 days. A longer grazing with-holding period is required under slow pasture growing conditions or where the quantity of compost used is more than 15 cubic metres per hectare.

What is mortality composting?

Mortality composting is generally conducted in three stages. In the first stage of composting, the pile is left undisturbed as soft tissue decomposes and bones partially soften. The compost is usually then moved, turned or mixed to begin the second stage, during which time the remaining materials (mainly bones) break down further.

Following completion of the second stage, the composting process is completed during a curing or storage phase.

The first (and sometimes second) stage of composting is characterised by high temperatures (>55°C); these conditions result in the elimination of nuisance odours and destruction of pathogens (disease-causing organisms) and weed seeds.

Site selection

The site should be located in an elevated area with soils that have low permeability. It may be possible to use an existing hardstand area or a disused concrete pad for composting dead farm animals. If neither is available, a hardstand area that provides all-weather access may need to be established. Instructions for constructing a hardstand area are available in Mortality Composting – Training manual. EPA Victoria’s Designing, composting & Operating Composting Facilities contains information on constructing a hardstand area.

Additional requirements include the following:

- The water table at the site must be at least two metres below the surface, taking into account site specific geology and impact into groundwater.

- The site must not be within 200 metres of surface waters (such as streams, lakes, wells).

- The site should be at least 300 metres from neighbouring houses.

- The site should be on elevated land with a slope of less than five per cent to allow proper drainage and prevent pooling of water following a rain event.

- Run-off from the composting facility (such as during a heavy rainfall event) should be directed to an effluent pond or a vegetative filter strip / infiltration area.

- The site should have all-weather access and have minimum interference from other traffic.

- Consideration should be given to prevailing winds and the location and proximity of the site in relation to the farm house and neighbours in order to prevent potential odour problems.

- Fence off the site to help eliminate scavenging animals and other livestock accessing the piles.

How is composting done?

How is composting done?

The instructions in this note is for composting cattle using the open pile method, which is likely to be the method of choice for most farmers.

Constructing the pile

The construction of the pile requires considerable quantities of carbon material (eg. sawdust, wood shavings); about 10–12m3 is needed to establish a composting pile for a 450kg carcass. Up to 50 per cent of carbon material can be comprised of finished compost from previous composting piles.

Follow this process for constructing a mortality composting pile:

Follow this process for constructing a mortality composting pile:

- Establish a base layer of relatively dry carbon material at the composting hardstand area (Figure 1). The depth of the base layer should range between approximately 45 cm for small carcasses and 60 cm for large carcasses. The dimensions of this base layer must be large enough to accommodate the carcasses with >60cm space around the edges.

- Place the carcass in the centre of the base layer

(Figure 2). - Cover the carcass with carbon material to a depth of about 60 cm (Figure 3). The material used to cover the animal should be damp to enhance the composting process. The material must feel moist but not be too wet. Composting material is too wet when water can be squeezed from it (droplets appear between fingers).

- Leave the pile undisturbed for at least four months. Provided that the animal is covered well enough, scavengers should not be attracted to the pile.

- When the soft tissue has completely decomposed after four to six months the pile can be turned and watered (Figure 4) to complete the composting process.

- When the pile starts to cool down, leave it to cure for at least another four weeks before using the compost. It is not necessary to turn the pile during the curing stage.

Although the composting process is complete, large bones of adult cattle such as the skull, the spine, shoulder blades or leg bones may still be present. However, they are usually ‘clean’ (free of soft tissue) and have become brittle, starting to disintegrate (Figure 5).

Although the composting process is complete, large bones of adult cattle such as the skull, the spine, shoulder blades or leg bones may still be present. However, they are usually ‘clean’ (free of soft tissue) and have become brittle, starting to disintegrate (Figure 5).

Monitoring the composting process

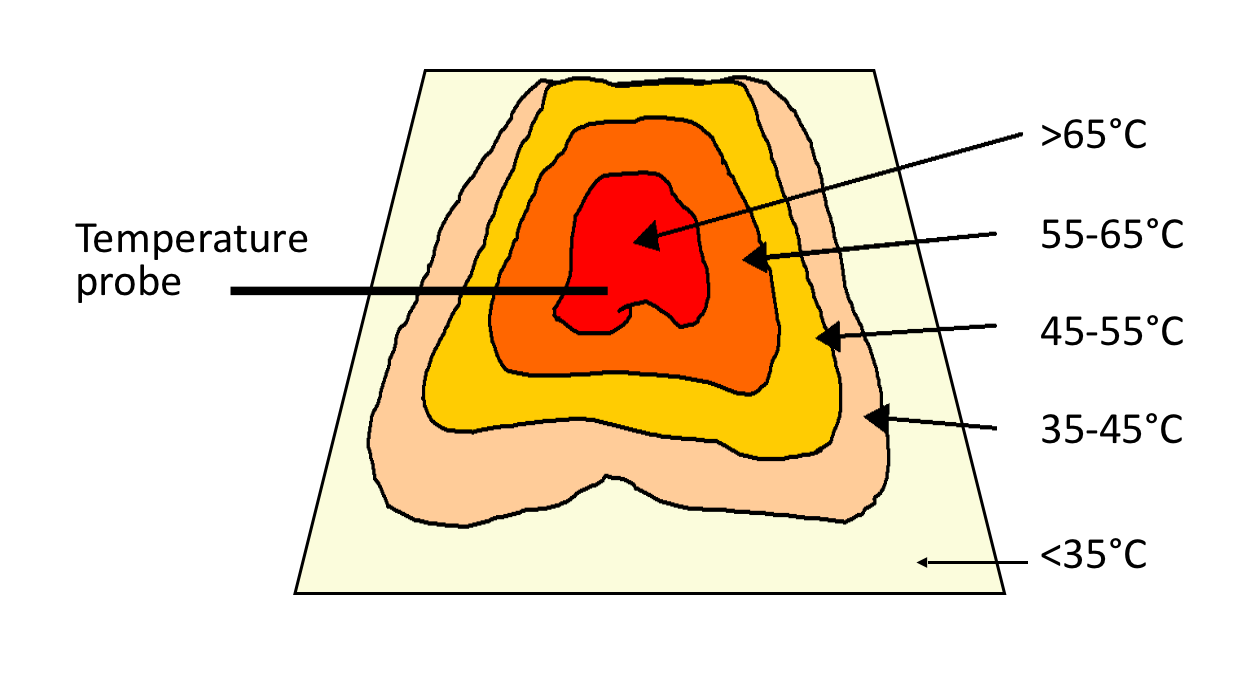

- Monitor compost pile temperatures (> 60cm depth) weekly for the first four weeks after establishing the pile and after turning (Figure 6). Subsequently, fortnightly measurements should be sufficient. Take temperature readings (three are suggested) from several points in the pile and record them down for future reference.

- After establishing the pile, visit the pile daily for the first week, to ensure there is no odour or liquid running from the base of the pile, and no dogs or foxes have dug into the pile to get access to the carcass. Add more carbon material if needed to cover the animal or to mop up seeping fluids.

- From about four months (less for younger, smaller animals), periodically check for signs of remaining soft tissue. If none remains, the pile can be turned and watered as described above.

Biosecurity

Composting is known to control nearly all pathogens - viruses, bacteria, fungi, protozoa (including cysts) and helminth ova to acceptably low levels. Exceptions to this are some spore-forming bacteria (such as Bacillus anthracis, the bacterium causing anthrax) and prions that cause Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy (BSE, which is exotic to Australia). Prions (abnormal form of a normally harmless protein found in the brain) are highly resistant to both physical and chemical means of inactivating pathogens and for this reason it is assumed that composting will be ineffective in reducing infectivity of prion-infected carcasses.

Composting is known to control nearly all pathogens - viruses, bacteria, fungi, protozoa (including cysts) and helminth ova to acceptably low levels. Exceptions to this are some spore-forming bacteria (such as Bacillus anthracis, the bacterium causing anthrax) and prions that cause Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy (BSE, which is exotic to Australia). Prions (abnormal form of a normally harmless protein found in the brain) are highly resistant to both physical and chemical means of inactivating pathogens and for this reason it is assumed that composting will be ineffective in reducing infectivity of prion-infected carcasses.

Pathogens are killed during composting by multiple means, such as high temperatures, the direct and indirect effects of other microorganisms and the presence of organic acids and ammonia in the compost. Not only is temperature considered to be the most important factor in killing pathogens, it is also relatively easy to measure during composting.

The heat required for the inactivation of pathogens is a function of both temperature and length (time) of exposure. Exposure to an average temperature during composting of 55 to 60°C for a couple of days is usually sufficient to kill the vast majority of pathogens.

To achieve efficient pathogen kill, all materials in a compost pile must be exposed to high temperatures for prolonged periods. In piles, there is great variation in the temperature profile from the cool outside layers to the hot central mass (Figure 7). As a result, piles are usually turned periodically to expose the outer layers of the pile to high temperature composting. In mortality composting, piles are turned after the soft tissue has decomposed (stage 2).

Risk management

Skilled design and operation of mortality composting systems is very important to ensure that all material achieves adequate temperatures for long enough to kill pathogens. This can be achieved for mortality composting piles provided that temperature is monitored.

The current state of knowledge suggests that taking the following factors into consideration will reduce the potential biosecurity and fire risks associated with mortality composting:

- attention to site design and layout to minimise scavenging and contamination of ground and surface water with pathogens

- using a minimum two-stage composting system followed by the use of a curing phase to properly complete the composting process

- where possible, fully encapsulating mortalities in ‘clean’ carbon source; use sufficient carbon source to absorb liquids and odorous gasses produced during composting

- monitor and manage the composting process to maximise progress towards the full completion of composting (eg. temperature, monitoring, watering and turning)

- attention to basic standards of hygiene (eg. minimising pooling of water at the site, regular sanitising of equipment and keeping it separate from production facilities, use of personal safety equipment by compost operators)

- maintain appropriate fire control equipment and water supplies at the farm

- remove easily combustible materials from within nearby operating areas.

Health and safety

A compost pile contains living microorganisms including moulds, bacteria, fungi and protozoa. These microorganisms can cause adverse reactions, particularly in people with a weakened immune system, asthma or a punctured ear-drum, or those taking certain prescription medications. Dust particles or bioaerosols released from the pile during handling of the compost on rare occasions may cause skin irritations, eye infection or respiratory illness.

The following precautions should always be followed when handling dead stock or compost materials:

- wear gloves

- wash hands after handling dead stock or compost

- avoid breathing dusts or mists

- wear a particulate mask

- wear dust resistant eye protection

- wash work clothing regularly

- prevent injury when operating machinery.

Acknowledgements

This Technical Note replaces the Factsheet ‘On-farm Composting of Dairy Cattle Mortalities’ produced in 2007 by Dr Kevin Wilkinson, formally of the Victorian Department of Primary Industries and Johannes Biala, The Organic Force, Queensland.

Dairying for Tomorrow and the Australian Government Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry’s National Landcare Program are acknowledged for their contribution to the original Technical Note.

This Technical Note has been updated through Victorian State Government funding by Agriculture Victoria Dairy Services and Chief Veterinary Unit staff in consultation with EPA Victoria and the United Dairyfarmers of Victoria.

Further information

Rachael Campbell, Agriculture Victoria, Ballarat. Email rachael.campbell@agriculture.vic.gov.au or phone (03) 5336 6868.

Alternatively contact your local Agriculture Victoria Dairy Extension Officer.

Detailed instructions for mortality composting available on the Dairying for Tomorrow website.

Further information is available from local offices of the department, the Agriculture Victoria website or from the Customer Service Centre on 136 186.

Other articles on composting: