Avian influenza in Australia and worldwide 2017

Sarah Sloan

Acting Policy Officer (Epidemiology), Chief Veterinary Officer's Unit

Avian influenza (AI) is a highly contagious viral disease, to which all bird species are thought to be susceptible. Domestic poultry such as chickens, turkeys, quails, guinea fowl, pet birds and wild birds can be affected by AI.

Strains of the virus are categorised according to their molecular H and N types and the severity of the disease in poultry. Haemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N) are two surface proteins used to classify AI viruses into subtypes. A virus that has HA 5 protein and NA 1 protein is subtype H5N1. Usually, they are further classified as either low pathogenic (LPAI) strains, which typically cause few or no clinical signs, and or highly pathogenic (HPAI) strains which cause severe clinical signs and potentially high mortality rates among poultry.

There is currently no effective treatment available for birds with clinical signs of infection. Although vaccines are available for some subtypes of AI, routine vaccination is not permitted in Australia.

AI viruses can be spread through direct contact with secretions (faeces, respiratory) from infected birds, through contaminated feed and water, or can be carried on farm equipment. Wild birds do not commonly show clinical signs of infection, which allows them to act as a reservoir, and a vector on long-distance migrations.

Clinical signs of LPAI include:

- respiratory distress

- coughing, sneezing, or rasping respiration

- rapid drop in feed and water intake and egg production

- typical 'sick bird' signs – ruffled feathers, depression, closed eyes

- death of a small proportion of a flock (3 to 15 per cent).

Clinical signs of HPAI include:

- sudden death

- respiratory distress

- swelling and purple discolouration of the head, comb, wattles and neck

- coughing, sneezing, or rasping respiration

- rapid drop in feed and water intake and egg production

- typical 'sick bird' signs – ruffled feathers, depression, closed eyes

- diarrhoea

- occasionally, nervous symptoms.

Most AI strains do not infect humans but some strain types (H5N1 and H7N9) have that potential. H5N1 first emerged in 2003 and there have been numerous human deaths – but almost all victims have been associated with close contact with infected birds.

H7N9 is a strain of AI in poultry that caused human deaths in China when it emerged in 2013. Surveillance continues to show H5N1 is not present in Australia. Waterfowl, which are the normal hosts of AI and are thought to have had a role in the spread of H5N1 in Europe, Asia and Africa do not migrate to Australia. Many species of wading birds do migrate to Australia but they are not the normal hosts or spreaders of AI. Australia's strict biosecurity measures aim to prevent the disease coming into Australia through imported birds or poultry products.

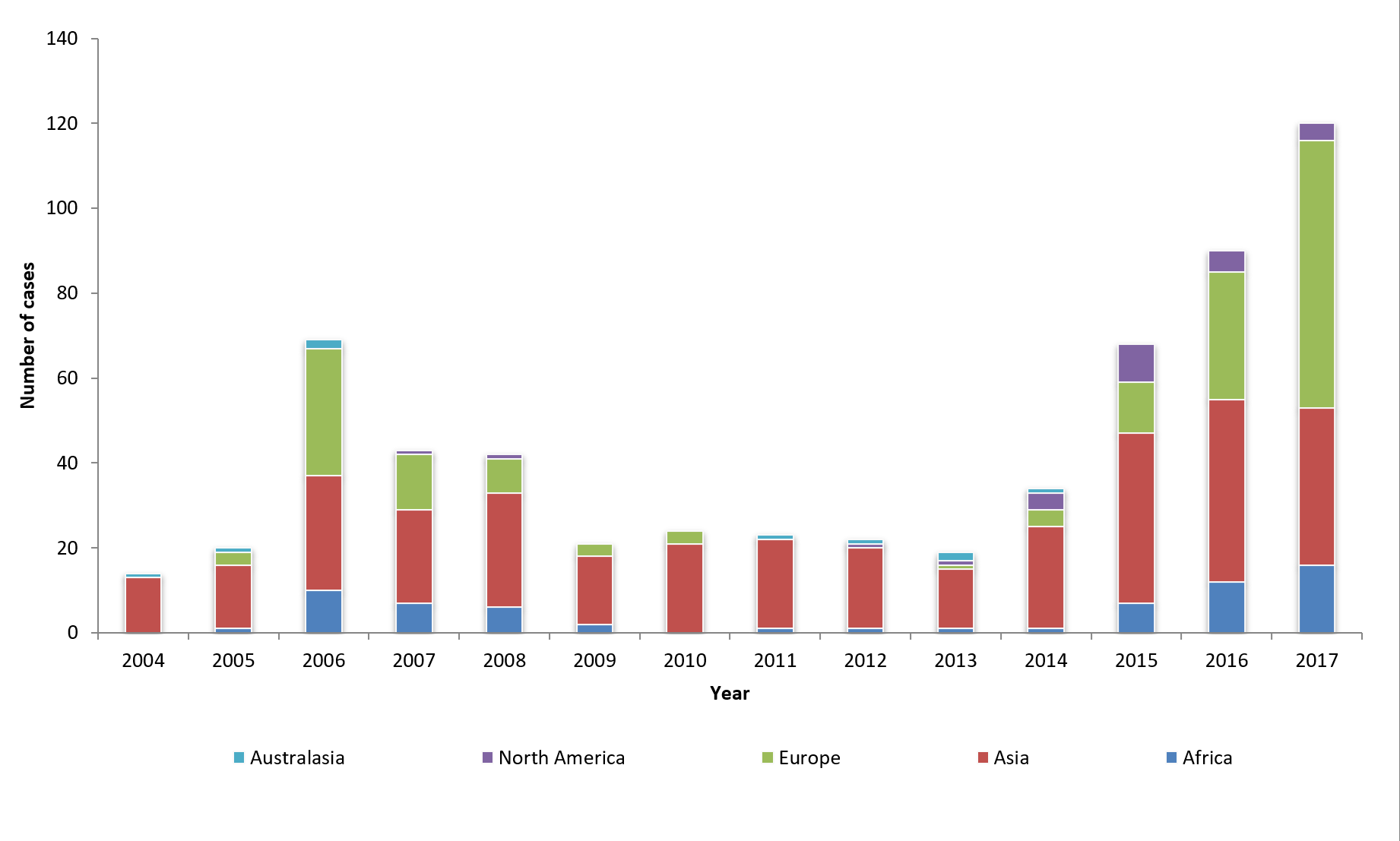

According to the World Organisation for Animal Health there has been a steady increase in the number of reported AI outbreaks since 2014 (Figure 1). There have been no recent cases of AI in Australia. Although, over the last 4 years there has been a steady increase in cases throughout Europe, there has been relatively little change in occurrence of countries neighbouring Australia.

Figure 1. Outbreaks of avian influenza reported to OIE – World Organisation for Animal Health, grouped by continent from 2004 to 2017

The Bar graph shows the number of reported cases of avian influenza (y-axis) from 2004 to 2017 (x-axis), grouped by continent. The graph shows an increase in cases in 2006, a decline in 2007 and 2009 and increases again in 2015, 2016 and 2017. The largest number of cases have been reported in Asia, followed by Europe, Africa, North America and Australasia.

See OIE's Avian influenza portal for updates on the status of AI outbreaks around the world.

What is the Australian Government doing about AI?

On-farm biosecurity measures include provisions to keep wild birds away from production birds in order to prevent potential transmission. Poultry farmers are supported by diagnostic laboratories and response plans in case of suspected or confirmed disease outbreak. Animal health authorities will use the procedures outlined in the Australian Veterinary Emergency Plan (AUSVETPLAN) should an outbreak occur. AUSVETPLAN includes measures such as the culling of infected birds, disposal method for carcasses and sanitation that will be adopted at infection sites to contain the disease.