To resow or not

Fiona Baker, Agriculture Victoria, Ellinbank

With an extended dry summer this year, some perennial pastures may be looking a little worse for wear. With autumn rains just hitting some or just around the corner for others, now is a good time to consider the condition of your perennial paddocks.

So how do you assess whether a pasture needs to be resown, or whether it has the potential to thicken up and tiller out after the break has hit?

Assessing the composition of the pasture for the proportion of perennial grasses is one of the best methods. If the desirable perennial grass species are above 70%, then the pasture is still productive. If the desirable perennial grass species are below 50%, then reseeding will increase yields, the feed value on offer to stock and the response that pasture could have to applications of nitrogen should you choose to use it. It is important to identify why the pasture has thinned out – is it soil fertility, grazing management issues or just tough seasonal conditions? If soil fertility or grazing management are the issue and it is not addressed, the same problem will keep on happening down the track.

There are a number of methods for assessing the composition of a pasture – stick, transect, motorbike, quadrat and boot method. They all follow similar principles of observing what is growing (if anything) at the assessment point. Details on how to do a composition assessment and record sheets can be found at http://mbfp.mla.com.au/pasture-growth/tool-27-field-based-pasture-measurements/

Choosing not to reseed once perennial grass levels have decreased significantly, increases the risk of weed invasion to both broadleaf weeds and annual grasses. Weed species tend to be both lower in feed value and have a shorter growing season, resulting in lower than expected animal performance.

When assessing perennial pastures early in the season before the break has arrived, a large portion of bare ground may be encountered. If the amount of bare ground is no higher than 30% it is unlikely that pasture production will be significantly impacted - particularly if it is clover that germinates and fills the bare ground areas.

If there is a large proportion of annual grasses invading the perennial pasture, it is important to be able to identify which species they are to be able to determine the best method for control. The most common annual grass invaders are barley grass, silver grass and winter grass.

Resources

The pasture paramedic booklet is a good resource for identifying different species and can be found via the Agriculture Victoria Feeding Livestock website for pasture ID resources.

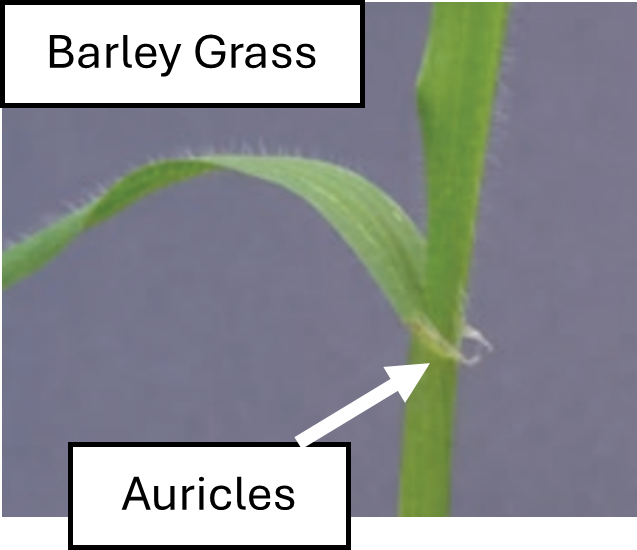

Barley grass

Barley grass seedlings tend to be a lighter green colour and lightly haired on the leaf and stem. Where the leaf joins the stem they have well developed auricles. The emerging leaf is rolled.

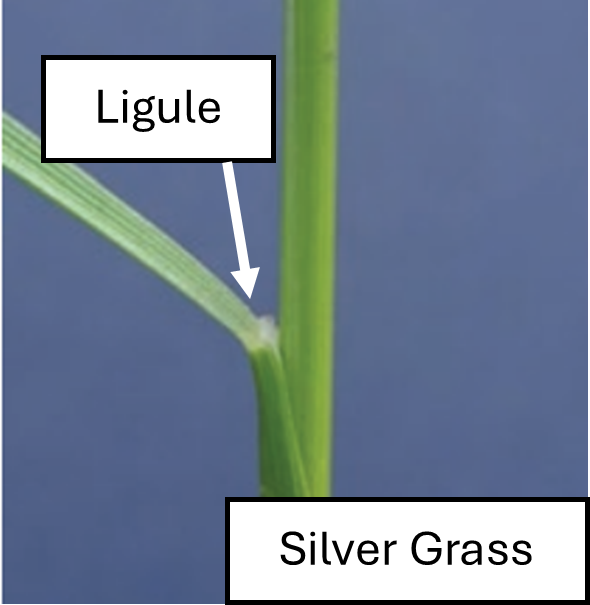

Silver grass

Silver grass is a very fine leaved grass. The leaves are hairless and the newly emerging leaf is rolled. It has a small membranous ligule but no auricle.

Winter grass

Winter grass tends to be a slightly lighter green colour, with the leaf and stem being hairless. The emerging leaf is folded rather than rolled.

If you find a large proportion of any of these annuals in your pasture, speak to your local agronomist or chemical reseller to find out your options for control prior to undergoing reseeding.

Resowing does not always mean a total renovation of the pasture. If there is still a reasonable amount of desirable species present, but you believe it needs to thicken up to minimise weed invasion, direct drilling into the existing pasture is generally the best method. Just be sure to graze out the pasture hard first and spray out any broad leaf weeds prior to drilling to minimise competition for the new emerging pasture. A lower cost option can be to broadcast new grass seed just prior to grazing and allow the stock to work the seed into the ground with their feet as they graze – just note, this option is generally not as successful as direct drilling.

Don’t forget to apply a small amount of phosphorus based fertiliser to ensure the new emerging pasture can readily access phosphorus from the soil. Phosphorus is important for healthy, strong root formation. Rates of 10-20 kg/ha phosphorus (114-227 kg/ha superphosphate/ha) would be adequate. The phosphorus can either be drilled in with the seed (best response) or broadcast around the time of sowing. Annual applications of phosphorus, potassium and sulphur to maintain soil fertility at adequate levels will help strengthen the pasture base.

As much as possible graze pastures according to readiness to graze based on leaf stage. Perennial ryegrass or fescues should be grazed at the 3-leaf stage, Phalaris, cocksfoot or prairie grass pastures at the 4-leaf stage. This will help with the persistence of these species and minimise the risk of weed invasion into the pastures down the track.