European rabbit

Common name: European rabbit

Scientific name: Oryctolagus cuniculus

Other common name: rabbit

Origin: Southern France and Spain

Animal status

Rabbits (feral or wild) are declared as established pest animals in the state of Victoria under the Catchment and Land Protection Act 1994 (CaLP Act)

Read more about the classification of invasive animals in Victoria.

Populations

History of spread

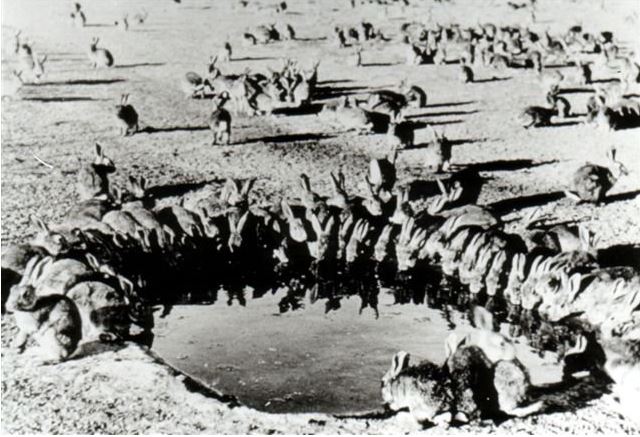

Various domestic breeds of rabbits were brought to Australia during early European settlement. Wild populations of rabbits were first reported on Tasmania by the early 1800’s, but they were unable to establish on the mainland until 1859, when Thomas Austin released at least thirteen wild rabbits at Barwon Park near Geelong. Just seven years after their release, over 14,000 rabbits had been shot on Barwon Park.

By the 1920s, rabbits had colonised most of the southern half of Australia and were present in extremely high numbers. The rate of advance varied from 10 to 15 kilometres per year in wet forested country to over 100 kilometres per year in the rangelands. The invasion of rabbits in Australia was the fastest of any colonising mammal in the world.

Distribution in Victoria

Rabbit densities are greatest in non-arable rough country. This includes creeks, riverbanks, erosion gullies and rocky outcrops.

Established Invasive Animals Best Practice Management video series

1. Rabbit control in Victoria

Hi, I'm Alex Pattinson, Leading Biosecurity Officer with Agriculture Victoria. Rabbits are one of the most destructive invasive species in Australia. This video gives an overview of the species and the management techniques landowners can use to control them.

The first successful attempt to establish wild populations of rabbits in Australia occurred in the late 1850s. By the 1920s, rabbits had colonised most of Southern Australia, making them one of the fastest spreading invasive mammals anywhere in the world.

Understanding basic rabbit biology and ecology helps you to identify the weaknesses that may be exploited in your control program for better results. rabbits are mostly active from late afternoon to the early morning, often emerging from their war in a few hours before sunset. They gradually graze further from it as it gets darker. Rabbits are shy feeders, and are often wary of new things in their environment. They also prefer to eat plants with the highest nutritional value. Rabbits also have a high reproductive capacity enabling them to recover quickly from poor seasonal conditions, disease outbreaks, and control efforts. One reason for their high reproductive capacity is their ability to dig extensive burrows or warrens. The Warren is the key to success of rabbits in Australia as it protects them from predators and weather extremes. Warrens are essential for breeding as rabbit kittens cannot survive the harsh Australian climate without shelter.

It's well known that rabbits have had a disastrous impact on Australia's economy and natural environment. It's estimated that rabbits cost Australian agriculture more than $200 million in lost production each year. To put the impacts of rabbits into perspective, seven rabbits account for one dry sheep equivalent. Rabbits selectively feed on certain species of plants, which affects the regeneration and recruitment, which changes landscapes over time. Rabbits also compete with native wildlife for food and habitat, and their excessive grazing habits often lead to soil erosion and reduced water quality.

Identifying rabbit activity on your property is the first step in managing this invasive species. Key signs of rabbits include 45 degree cuts on seedlings, rabbit dung, warren and burrow entrances, grazing lines, scratching and ring barking. Familiarise yourself with these signs and keep a lookout when monitoring your property.

Once you've identified rabbit activity, activity on your property or in your area, there's several things you can do. Perhaps the most important thing to remember is the warren is the key to the rabbit's survival. So if you remove the warren, you also remove the rabbit's ability to breed, reestablish numbers and rebound populations. It's important to use the season and climate to your advantage when selecting the timing of your control program as it will increase the effectiveness. The timing of when to use various control methods will be discussed in specific videos in this series.

There is a scientifically proven series of steps you can follow to manage rabbit populations, and it is often referred to as 'The Rabbit Recipe'. The steps include, monitor and coordinate your efforts with your neighbours. Reduce numbers which is best achieved by baiting. Destroy their harbour by ripping warrens, and removing above ground shelter, where applicable. Follow up when needed by reripping or fumigating any warren reopenings. Continue to monitor your property and react when needed. The best time to implement these control methods are summer break for baiting when other feeds are scarce, ripping immediately following baiting in the summer break when soils are friable and the warrens will collapse. Fumitigation to occur as follow up to ripping in the autumn and winter months. We'll provide more detailed information about each method in other videos in this series.

Rabbits are a major issue for landholders across Victoria. Their ability to reproduce quickly means they can also recover quickly after control if it's not done properly. Long-term control is possible if you use the right techniques at the right time and to the right standards. I encourage you to watch the other videos in this series for more detail on the methods I've mentioned. You can also find more information at the Agriculture Victoria website or contact the Customer Service Centre if you have any questions. Enjoy the videos, we hope you find them helpful. And thank you for playing your part in managing invasive animal species.

Animal biology

Appearance

European rabbits are small mammals that belong to the family Leporidae, which also includes hares.

Rabbits have long hind legs and short front legs. They also have long ears and slightly protruding eyes on the sides of the head that give them panoramic vision to detect predators.

Rabbits have unique upper teeth consisting of a pair of gnawing hypsodont teeth (which grow continuously) and a pair of peg teeth that are hidden behind. This double pair of upper teeth are only found in rabbits and hares, and they cause a distinctive 45-degree angle cut on browsed vegetation.

Male rabbits are known as 'bucks', female rabbits are called 'does' and young rabbits are 'kittens'. A rabbit's fur colour is typically grey-brown with a pale belly. Black or ginger rabbits do occur in the wild, though they make up less than 2 per cent of the rabbit population and white rabbits are rarely seen.

Adult rabbits usually weigh between 0.8 to 2.3 kg, while new-born rabbits weigh just 35 g. Juvenile rabbits moult at 3 months of age and frequently have a white star on their forehead, which they lose when they moult.

Behaviour

Rabbits are most active from dusk until dawn. They typically start grazing/socialising on or near the warren, but move further away as it gets darker. Rabbits often stay above ground during the night unless they are disturbed.

Rabbits are wary of new foods and changes to their environment. When threatened, they will crouch and freeze or try to sneak away. If this fails, they will sprint for the warren or cover, with the white underside of the tail showing as a visual warning to other rabbits. When close to cover, rabbits will respond to threats by thumping the ground with their back legs and vocalising to warn other rabbits.

Rabbits form social groups with complicated social structures. Dominant males defend their territory to gain mating rights, while dominant females defend access to nesting sites. At large warrens or where populations are dense, different social groups may share a common warren or feeding area.

The territory or home range of rabbits varies from approximately 0.2 to 2 ha depending on:

- rabbit density

- food availability

- sex

- age

- surface cover.

Diet

Rabbits need a high-quality diet to maintain body condition and for reproduction. As such, they are highly selective grazers, preferring plants, or parts of plants, with the highest nutritional value.

Rabbits generally obtain water from green vegetation but will travel to drink if they can't obtain enough water from their diet.

Like hares, caecotrophy (the re-ingestion of faecal material from the caecum) is a behaviour that is used by rabbits to gain the maximum amount of nutrients from their food.

Preferred habitat

Soils have a strong influence on rabbit density with deep, well-drained soils (sands and light loams) being most productive. Rabbit warrens are also typically larger and more complex in deeper soils.

Rabbits form extensive burrows or warrens for shelter. The warren is the key to the success of rabbits in Australia as they not only provide rabbits with protection from predators, but they also protect them from environmental extremes. Without this protection, rabbits are not able to successfully reproduce, as newborns are very susceptible to temperature extremes.

Rabbits can exist above ground where a surface harbour is present. Fallen timber and logs, rocks, dense thickets of native scrub and woody weeds along with heaps of debris are ideal shelter. Rabbits may also become a problem around houses, farm buildings and other structures such as water tanks, as human activity does not deter them.

Predators

In Australia, the most significant predators of rabbits are:

- red fox

- feral cat

- wild dogs and dingoes

- goannas

- large birds of prey such as wedge-tailed eagle.

Diseases and parasites

In Australia rabbits are affected by internal parasites such as:

- coccidia

- intestinal and stomach worms

- dog tapeworms

- species of liver fluke.

Important external parasites on rabbits in Australia include the introduced European and Spanish rabbit fleas, which are important vectors in the spread of myxomatosis.

There are also two types of diseases in Australia that are deadly to rabbits, including Myxoma virus (MV) and rabbit haemorrhagic disease virus RHDV (formerly known as calicivirus). These diseases were brought to Australia as biological control options for rabbits and now occur throughout much of the rabbit’s range.

Variable virulence and increased genetic resistance have lessened their effectiveness on rabbits over time. Therefore, efforts are being made to identify more virulent strains of RHDV. Notwithstanding, MV and RHDV still limit rabbit numbers to about 15% of what they could be. Without them, the additional cost to agriculture alone could be over $2 billion a year.

Reproduction

Rabbits have an extremely high reproductive rate, with a single pair of rabbits being able to increase to 184 individuals within 18 months.

That said, rabbits do require protein-rich, fresh growth to successfully reproduce. Therefore, most breeding in Victoria commences at the autumn break and continues until vegetation dries off by early summer.

Rabbits become sexually mature at 3 to 4 months of age. Their gestation period is 28 to 30 days and they often have litters between 4 and 6 kittens. Kittens are born blind, deaf and almost naked in either short nesting burrows or above-ground nests. Mating can recur immediately after giving birth.

Dispersal

Rabbits have high rates of dispersal which occur during two separate dispersal events. The first occurs during, and immediately after, the breeding season, where about 60% of young male and female rabbits disperse from the breeding warren to find unused burrows and safe above-ground harbour.

The second occurs just before the breeding season (late autumn/early winter), where sub-adult males move to new areas.

Most rabbits disperse short distances to join adjacent social groups. However, movements of up to 20 km have been recorded.

During dispersal, rabbits are vulnerable to predation and environmental extremes. Despite common opinion, rabbits do not readily dig new warrens and instead prefer to find an unused warren to excavate.

Impact

Impact on ecosystems and waterways

The impact of rabbits on the Australian environment has been disastrous. At least 304 Australian threatened fauna and flora species are currently affected by competition and land degradation by rabbits. Consequently, rabbits have been listed as a key threatening process to threatened species conservation under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act).

Rabbits selectively feed on certain species of plants at critical stages of their development, such as seeding and seedling establishment. This severely affects regeneration and recruitment and can cause soil erosion. It may also replace native species with noxious or unpalatable weed species.

Ecological changes associated with high rabbit numbers have been blamed for the disappearance of the greater bilby Macrotis lagotis and the pig-footed bandicoot Chaeropus ecaudatus, as well as putting many other species under stress.

Research in semi-arid sites has shown less than 1 rabbit per hectare (1 rabbit per 2 hectares) can severely damage some plant species.

In certain areas, rabbits are also in direct competition with native wildlife for food and habitat.

Rabbit populations can also sustain high numbers of predators such as cats and foxes. This can cause increased pressure on native animals, particularly when rabbit numbers crash after control, drought or disease. Therefore, it is important to control foxes before undertaking rabbit control.

Agricultural and economic impacts

It has been estimated that rabbits cost Australian agriculture over $200 million in lost production every year. In Victoria and Tasmania alone, it’s estimated that rabbits cost $30 million in lost production for the beef, lamb and wool industries per year.

Rabbits graze more closely to the ground than domestic stock, weakening perennial grasses during summer and potentially eliminating them from established pastures. The pasture is then likely to be invaded by broadleaf weeds and annual grasses, making it less suitable for livestock production

Rabbits also affect revegetation projects when they feed on newly planted vegetation. Even low numbers of rabbits can have a devastating effect on tree-planting programs or intensive horticultural operations. Rabbits also cause damage to grain crops and have significantly reduced crop yields in some areas.

Management

Recommended control measures include:

- baiting

- ripping

- harbour management where applicable

- fumigation.

Where a land owner is served with a control notice, such as a Directions Notice or Land Management Notice, in accordance with the Catchment and Land Protection Act 1994, the land owner must comply with the specific requirements of that notice including undertaking the required measures listed in that notice during the stipulated time frame.

The department recommends an integrated approach that includes baiting, ripping/harbour removal and follow up fumigation. This approach is often referred to as the 'Rabbit Recipe'. Landholders should also implement their control program in a coordinated manner at a landscape scale.

Read more about European rabbit management.

Victorian Rabbit Action Network (VRAN)

The Victorian Rabbit Action Network (VRAN) is a not for profit, community pest management organisation that was established in 2014 to promote long-term reductions in Victoria’s rabbit populations, to enhance and protect the natural environment and sustainable agricultural production and secure cultural heritage and community assets.

VRAN work with all Victorians currently involved in the management of rabbits on private or public land including farmers, Landcare, community groups, Traditional Owner organisations, local and state government organisations and rail/water/catchment management authorities.

VRAN also runs training and mentoring programs, deliver workshops on best-practice rabbit control, help design strategies and action plans and supports people and organisations to collaborate on rabbit action. Occasionally, they also provide funding grants to support community learning, innovation and rabbit management.

To find out more, please visit the VRAN website.

Image credits

Figure 1 courtesy of Chris Lane

Figure 2 courtesy of Anne Young

Further reading

- Brunner, H., Stevens P, L., Backholer J. R. (1980) Introduced Mammals in Victoria. Proceedings of a Symposium Held at Rusden C.A.E. July 1980.

- Caughley, G.C. (1977). Analysis of Vertebrate Populations. John Wiley, London.

- Commonwealth of Australia (2016). Background document to the Threat abatement plan for competition and land degradation by rabbits.

- Cooke, B. D. (1974). Food and other resources of the wild rabbit Oryctolagus cuniculus (L.). Ph.D. Thesis, University of Adelaide.

- Cowan, D.P. (1987). Group living in the European rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus): mutual benefit or resource localisation. Journal of Animal Ecology 56: 779–795

- Cooke, B.D. (2007). A review of rabbit haemorrhagic disease in Australia - a report prepared for Australian Wool Innovation and Meat and Livestock Australia (Unpublished) pp 82

- Croft, J.D.(1995) in Williams K, Parer, Coman B, Burley J & Braysher M, Managing Vertebrate Pests: Rabbits Bureau of Resource Sciences and CSIRO

- Douglas, G.W. (1969). Movements and longevity in the rabbit. Vermin and Noxious Weeds Destruction Board Bulletin No. 12.

- Gibb, J.A. (1993). Sociality, time and space in a sparse population of rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus). Journal of Zoology, London 229: 581–607.

- Gong, W., Sinden, J., Braysher, M. and Jones, R. (2009). The economic impacts of vertebrate pests in Australia. Invasive Animals Cooperative Research Centre.

- Greenwood, Bridgewater, and Potter (1995), in Williams K, Parer, Coman B, Burley J & Braysher M, Managing Vertebrate Pests: Rabbits Bureau of Resource Sciences and CSIRO

- King, D. (1990) quoted in Williams K, Parer, Coman B, Burley J & Braysher M (1995), Managing Vertebrate Pests: Rabbits Bureau of Resource Sciences and CSIRO

- Lange, & Graham(1995), in Williams K, Parer, Coman B, Burley J & Braysher M, Managing Vertebrate Pests: Rabbits Bureau of Resource Sciences and CSIRO

- Mallet, & Cooke, B. (1995), in Williams K, Parer, Coman B, Burley J & Braysher M, Managing Vertebrate Pests: Rabbits Bureau of Resource Sciences and CSIRO

- McLeod, R. (2004) Counting the Cost: Impact of Invasive Animals in Australia 2004. Cooperative Research Centre for Pest Animal Control. Canberra

- Myers, K., Parer, I. and Richardson, B.J. (1989) Leporidae. Pp. 917–931 in: Fauna of Australia, eds. D.W. Walton and B.J. Richardson, Australian Government Publishing Service, Canberra, Vol. 1B.

- Newsome, A.E. (1975) ) quoted in Williams K, Parer, Coman B, Burley J & Braysher M (1995), Managing Vertebrate Pests: Rabbits Bureau of Resource Sciences and CSIRO

- Parer, I. (1977). The population ecology of the wild rabbit Oryctolagus cuniculus (L.) in a Mediterranean-type climate in New South Wales. Australian Wildlife Research 4: 171–205.

- Parer, I. and Libke, J.A. (1985). quoted in Williams K, Parer, Coman B, Burley J & Braysher M (1995), Managing Vertebrate Pests: Rabbits Bureau of Resource Sciences and CSIRO

- Parker, B. S. and Bults, H.G. (1967) quoted in Williams K, Parer, Coman B, Burley J & Braysher M (1995), Managing Vertebrate Pests: Rabbits Bureau of Resource Sciences and CSIRO

- Pickard (1995), in Williams K, Parer, Coman B, Burley J & Braysher M, Managing Vertebrate Pests: Rabbits Bureau of Resource Sciences and CSIRO

- Rolls, E. (1969). They All Ran Wild. The Story of Pests on the Land in Australia. Angus & Robertson : Sydney.

- Sloane Cook and King Pty Ltd., (1988) 'The Economic Impact of Pasture Weeds, Pests & Diseases on the Australian Wool Industry' Australian Wool Corporation.

- Stead, D.G. (1935) The Rabbit in Australia

- Stodart, E. and Parer, I. (1988). Colonisation of Australia by the rabbit. CSIRO Division of Wildlife and Ecology Project Report No. 6.

- Wagner, F. H. (1981) ) quoted in Williams K, Parer, Coman B, Burley J & Braysher M (1995), Managing Vertebrate Pests: Rabbits Bureau of Resource Sciences and CSIRO

- Williams, K., Parer, I., Coman, B., Burley, J., and Braysher, M. (1995). 'Managing vertebrate pests: rabbits'. (Australian Government Publishing Service: Canberra).

- Williams, C.K., (1991). Efficacy, Cost and Benefit of Conventional Rabbit Control. Australian Wool Corporation.

- Williamson, Chapman & Hall (1996) Biological Invasions