Enhanced producer demonstration site update: Managing sheep worms in East Gippsland

Key points

- Know the efficacy of worm drenches on your farm with a post-drench check or WECDRTs.

- Monitor WECs, use a product that is effective and dose the correct animals at the correct time.

- Alternating grazing with sheep and cattle every 6 months is a free kick for worm control.

Ben Blomfield, Mackinnon Project

Control of intestinal parasites in sheep is becoming more challenging as drench options become more limited. Producers still rely heavily on drenches to control worm burdens in sheep but many producers have limited knowledge of how effective these drenches are.

Drenches that producers once thought would reliably keep worms under control are now failing. Initially this goes unnoticed, but over time, if the same drench group is used, the impacts become more noticeable. For example, lambs take longer to finish, ewes lose weight despite adequate feed, an extra crutch may be needed because of more dags.

This article is an update of an ongoing enhanced producer demonstration site (EPDS) that Mackinnon Project has been involved in, which is jointly funded by Meat & Livestock Australia and Agriculture Victoria. This project commenced in late spring of 2024, with an aim to demonstrate integrated management methods to control sheep worms in East Gippsland.

EPDS project outline

Included in the project are face-to-face workshops, a worm egg count drench reduction trial (WECDRT) and larval cultures.

The project kicked off with the face-to-face workshops. These primarily focused on the major worm species, their impact and an overview of worm management. This included information on monitoring drench efficacy and how to perform a WECDRT.

The sessions also included an overview of the worm life cycle in sheep. As tedious as a lot of producers may find this, it gives them an understanding of the strategic timings of when to drench in order to disrupt the development of worms. In addition, the sessions covered the weather patterns under which the different worms thrive. This allows producers to predict larval die-off and therefore adjust management in high-risk seasons. This awareness allows effective integration of grazing, monitoring and drenching to sustainably manage worms in sheep and on the pastures.

WECDRTs

Following these workshops there were 9 producers interested in completing WECDRTs. Most of the farms completed these trials in undrenched weaners. Some had to complete a pre-trial monitor to make sure enough eggs were present to set up the WECDRT.

Across the 10 farms, 15 different drench actives or combinations of actives were tested. The drenches used depended on what the producers had on hand at the time. Of the 15 different drenches, 8 were used on 6 or more farms. Although this is only a small sample size, it demonstrates that every farm is different. An important take-home message from this is that drench resistance status is different for every farm and you won’t know unless you do a WECDRT on your farm.

The results for the WECDRT are calculated by comparing the worm egg count (WEC) of the sheep in each drench group to a control (untreated) group of sheep in the same mob. Typically, a WEC reduction of less than 95% compared to the control group indicates resistance to the drench used in that group. For reference, for a summer drench we recommend a product with a greater than 98% efficacy.

Larval culture

Following the WECDRT, larval cultures were set up using the control group faeces to determine the resistance status of the 3 species of worms that cause the most significant production losses in sheep in East Gippsland. These are barber’s pole worm (Haemonchus contortus), black scour worm (Trichostrongylus spp.) and small brown stomach worm (Teladorsagia circumcinta).

Barber’s pole worm (BPW) was present in 8 of the 9 control samples. Apart from 2 farms that had a BPW population consisting of over 60% of the total sample, the average percentage of BPW present on the remainder of the farms tested was 21%.

Black scour worm was present in 8 of the 9 control groups, making up on average 32% of the worm population across the farms tested. Small brown stomach worm was present in all 9 control samples submitted to the lab and on average made up 34% of the worm population found on the farms tested.

WECDRT results

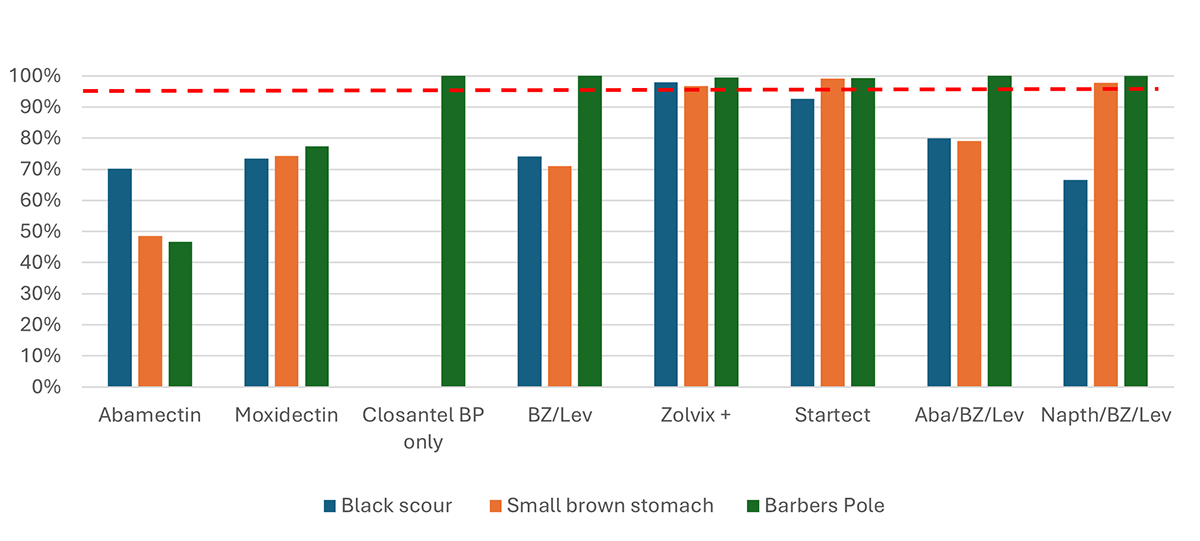

Figure 1 illustrates the average WEC reduction for the different species of worms for each different drench group used in the project.

Figure 1: The percentage reduction in WEC counts compared to the control group for each different worm species and drench group used. (The red hashed line shows 95% reduction.)

Single active drenches

Predictably, the single active drenches demonstrated very poor efficacy against all 3 species of worms.

Encouragingly, the exception to this trend was Closantel, a narrow-spectrum drench (only effective against a small number of internal parasites) used strategically to control BPW. On the farms where it was tested as a single active, it remained 100% effective against BPW.

Likewise, drenches that included the active levamisole are still effective against BPW. This gives these farms options for tactical BPW control in their broader integrated parasite management plan.

While the poor performance of the macrocyclic lactones (MLs) tested as single actives is not a surprise, it certainly demonstrates that relying on drenches alone will not cut it for long-term worm control.

Combination drenches

It’s well established that using combination treatments slows resistance. However, timelines for resistance once components of combinations are failing appear to be concerningly short. The effects of a combination drench are shown in Figure 1 compared to single actives. This combined effect has been demonstrated where there is significant resistance of some species of worms to single abamectin and the dual BZ/Lev combo, but as a triple combo it’s still 100% effective. Despite this, efficacy will be short-lived if other actives or management practices are not integrated into worm management on these farms.

Concerningly, MLs form the spine of most drench treatments commonly available. This is of concern because where abamectin is failing, as has been demonstrated on some farms in this project, it is increasing the selection pressure on the remaining drench actives. Drenches such as Startect and Zolvix Plus essentially revert to becoming more like a single active product once the efficacy of abamectin reduces. Anecdotally, we are more commonly observing reductions in efficacy of these products as active components fail – some only lasting a few seasons before dropping dramatically in efficacy.

Use of long-acting drench products

Some farms have historically had a heavy reliance on long-acting (LA) moxidectin as a pre-lamb treatment. Traditionally it was used without a primer (an effective drench given prior to a long-acting product) or tail cutter (an effective drench given towards the end of the effective period, once eggs start to appear) on some farms. An assumption based on the results from this project is that some side resistance has occurred as a result of this extended use. This means that overusing moxidectin LA it has concurrently selected for resistance genes in that particular worm population to MLs, inadvertently reducing the efficacy of the less potent abamectin.

Variation in results

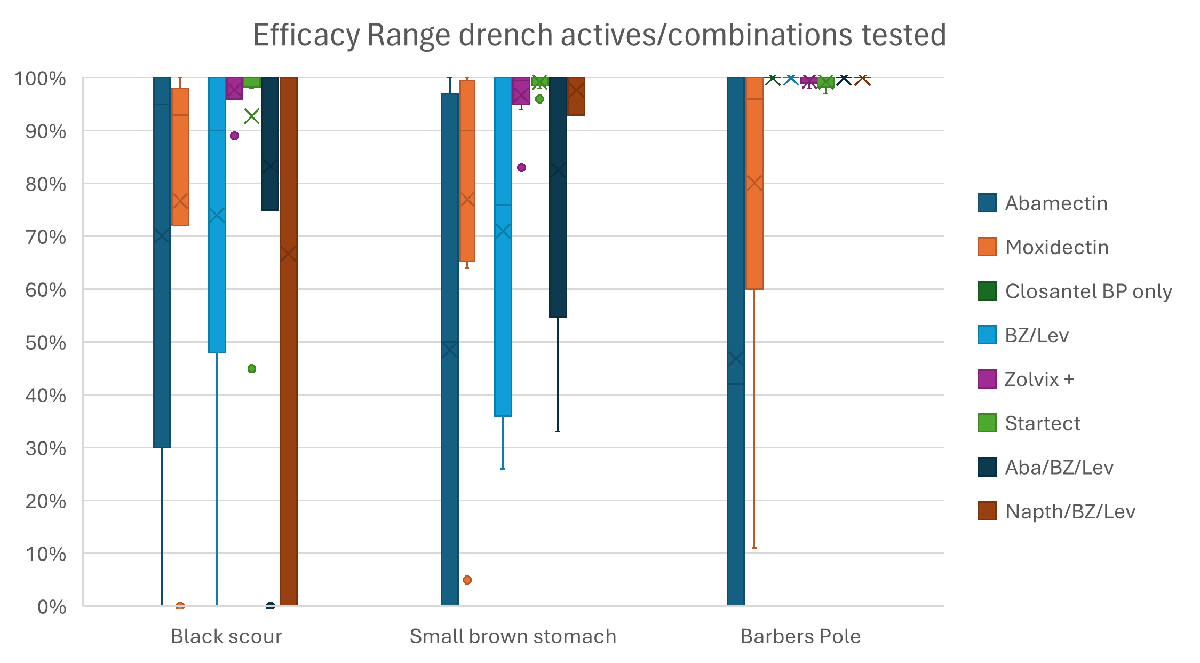

Figure 2: The range in drench effectiveness for each different drench group for each different worm species using data from all the farms included in the trial

Figure 2 demonstrates the variability of drench resistance of each worm species across the trial farms.

When looking at these results, the worm species present in control samples and the percentage that each species contributes to the overall population must be considered. This plays a role in the level of confidence that the results represent the flock resistance status on each farm. Hatched larvae numbers in control samples will give an indication of what is present on farm at that time.

Along with using a 95% reduction threshold to indicate drench resistance, the Mackinnon Project lab also calculates confidence intervals to take into account variability in test results. This ensures the observed reduction in WECs is not due to random variation but reflects true resistance.

To do this, 95% confidence limits (CLs) are used. If the lower 95% CL falls below 90% this signals that resistance is statistically significant. This means that, based on the data, the true reduction could be lower than 90% by taking into account the variation in the samples submitted. This indicates there is some evidence of possible resistance or at least uncertainty about the drenches’ reliability even if the WEC reduction was above 95%.

Several farms had individual drenches where the observed reduction was 95% or greater but had a 95% CL below 90%. In these cases, the drench appears effective but the results also suggest we cannot be confident the drench will consistently achieve control.

This highlights the need to test the efficacy of the drenches you are using every 3 to 4 years.

What does this resistance mean?

It is well known that the effects of worms are more severe in young animals and late-pregnancy and lactating ewes, especially in maiden and older ewes.

Some production loss is inevitable even when relatively immune sheep are exposed to infection. Losses include 3% to 5% lower bodyweights and 10% less wool production in both Merinos and prime lamb breeds. Decreased growth rates also occur in rapidly growing prime lambs, although these effects can be contained when the amount and quality of pasture offered is adequate.

Kirk (Kirk et al., 2021) also found ewes were more vulnerable to parasitism when immature, twin-bearing or under nutritional stress. The effects of worms were reduced when periparturient ewes (ewes shortly before and after giving birth) were held in optimal body condition score and grazed adequate pastures.

In addition to the production impacts are the costs associated with scouring. The accumulation of faeces on the breech wool, ‘dag’, is associated with increased costs due to additional crutching and increased crutching time, as well as the reduced income from a reduction in fleece value. In addition, dag is also a major risk factor for breech strike, which itself comes with increased costs.

Research completed in the nineties in WA looked at the effects of using a drench that was 100% effective compared to drenches that were 85% and 65% effective against scour worms in Merino weaners. Over the production cycle of the weaners, there were significant production and disease effects of using a 65% effective drench compared to a drench that was 100% effective. There was a 10% (450 g) reduction of greasy wool and even though it was finer, there was an overall loss in fleece value. Body weights averaged 6 kg lighter, with 3 times as much scouring (60% vs 20%, for 65% and 100% effective, respectively) and a sharp reduction in drench effectiveness over the year (65% effective reduced to 38%).

Overall, this represents a loss of over 10% in profitability. Interestingly, the author noted the low drench efficacy groups did not look ‘too bad’ and without the comparison groups the potential loss would have been very difficult to pick. The losses in the 85% effective drench group were smaller (3% to 5% less compared to the 100% effective drench group), but with virtually no visible signs.

Conclusion

There is no silver bullet for worm control in sheep. Enterprises that manage effective worm control programs use strategically timed drench treatments that are integrated with other control options. These include:

- testing for drench resistance

- monitoring worm egg counts

- grazing management by utilising species cross-over

- selection of sheep with enhanced immunity to worms.