Grazing value of summer weeds

Some weeds can cause animal health issues (see Toxic summer weeds). Others have nutritional value to sheep which may be worth considering before deciding to spray them out. This page focuses on summer weeds.

Generally, a good quality sown perennial pasture will contain 30–50 per cent sown grass and 20–40 per cent subterranean clover with annual volunteer weeds making up the rest of the pasture. Our Mediterranean pastures (without summer responsive species) decline in energy and protein as the plants go to seed and then die off. High-quality pastures may retain sufficient quality to maintain dry animals for the duration of summer–autumn but poorer quality pastures cannot.

In the absence of a summer active pasture species (like lucerne), summer weeds can be of value. Green pick over summer can provide protein, which is a necessary component of the diet and is important for the digestion of the low-quality dry feed. Ruminants struggle to digest enough pasture when the protein drops below six per cent.

Recent work by Jess Brogden and Lisa Miller at Southern Farming Systems (SFS) has documented the nutritive value of weeds that grow during the summer-autumn (Table 1). Their work is published as a Weed Fast Facts on the MLA weeds hub and SFS website.

Table 1 shows the nutritive value, as tested by FEEDTEST, of some weeds that are potentially useful over summer. Metabolisable Energy (ME) is the energy content of the plant. It is usually converted into megajoules in a kilogram of dry matter per hectare (MJ ME/kg DM/ha), to reflect how much of the feed an animal requires (like kilojoules per 100 g for humans). Dry matter is used so that plants of different water content are comparable in nutrient density. Crude protein is an assessment of the level of nitrogen in the pasture.

Table 1. Energy and protein content of weeds during January to March (Miller, Brogden and Nicholson 2021). The range reflects the quality drop from germination to March.

| Weed group | Metabolisable Energy (MJ ME/kg DM/ha) | Crude Protein % | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

Dandelion/flatweed | 8–10 | 9–15 | N/A |

Sorrel | 8–9 | 10–16 | January and March figures |

Wireweed/hogweed | 8–10 | 9–20 | N/A |

Wild radish/mustard | 13 | 29 | November only |

Thistles, e.g. sow, milk | 8–10 | 6–30 | Highest when young and green |

Glammy goosefoot/mintweed | 8–10 | 9–30 | N/A |

Fat hen | 8–10 | 20–40 | N/A |

Windmill grass | 8–10 | 7–16 | N/A |

Bent grass | 6–8 | 6–8 | January only, no February or March figures |

Green/Spraytopped Bent Grass | 9 | 13 | December in lieu of actual Feb–Mar figures |

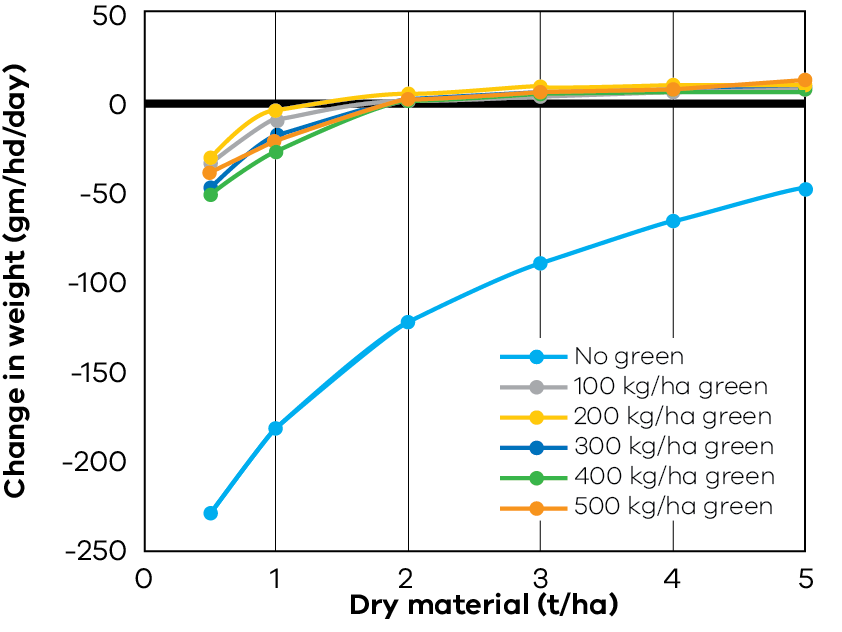

In later summer, a fairly average or low-quality pasture has a Metabolisable Energy of less than five MJ ME and Crude protein of about six per cent, which is insufficient to maintain liveweight in dry sheep no matter how much pasture there is. The addition of a green pick can be enough to maintain liveweight (see ‘Underperforming animals in a paddock full of feed’ in the last edition of SheepNotes for more information on protein requirements). As part of a presentation on the value of weeds at the BestWool/BestLamb conference in 2019, Cam Nicholson showed Figure 1 to illustrate the value of a small amount of green on live weight in a dry pasture.

The graph shows the effect of some incidental summer weeds on dry ewe liveweight. Essentially the effect was similar with 100 or 500 kg DM/ha of weed, on the proviso that the green was of reasonable height, for example five cm high, so the sheep didn’t have to work too hard to access it. This highlights the value of a summer rotation to allow incidental summer weeds to accumulate some height before grazing. Cam also commented that stressed-out looking weeds can maintain their nutritive value.

Figure 2 provides an example of what 100 kg of green dry matter per hectare, might look like.

The pros and cons of grazing, rather than spraying out summer weeds in your pasture needs be considered in terms of how it affects the preferred grasses and clover during the growing season (competition for resources of light/shading, water and nutrients), problematic seeds for livestock, issues of toxicity and chances of success, for example buried wireweed/hogweed seed can last for 60 years.