What is soil?

Soil is the loose surface material that covers most land. It consists of inorganic particles and organic matter. Soil provides the structural support for plants used in agriculture and is also their source of water and nutrients.

Soils vary greatly in their chemical and physical properties. Processes such as leaching, weathering and microbial activity combine to make a whole range of different soil types. Each type has particular strengths and weaknesses for agricultural production.

Physical characteristics of soil

The physical characteristics of soil include all the aspects that you can see and touch, such as:

- texture

- colour

- depth

- structure

- porosity (the space between the particles)

- stone content.

Good soil structure contributes to soil and plant health, allowing water and air movement into and through the soil profile. Soil stores water for plant growth and supports machine and animal traffic.

While some soils are naturally better structured than others, some physical characteristics of soils can be changed with good management.

It is important to monitor the physical characteristics of soil to understand soil conditions.

It is also important to ensure that management practices are not contributing to the decline of the soil. An example of this is excessive traffic causing compaction and reducing the amount of macropores, or spaces between the aggregates, therefore reducing the amount of air and water into and through the soil.

Soil texture, structure, drainage characteristics

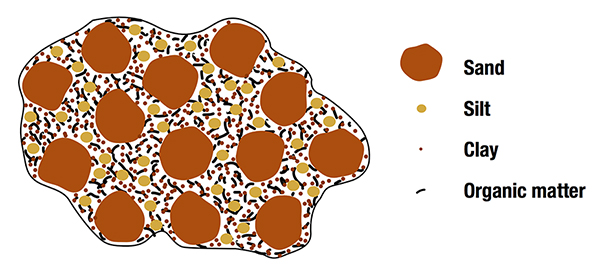

The combination of mineral fractions (gravel, sand, silt and clay particles) and organic matter fraction give soil its texture. Texture grades depend upon the amount of clay, sand, silt and organic matter present.

The solid part of the soil is made up of particles such as organic matter, silt, sand and clay which form aggregates. Aggregates are held together by clay particles and organic matter. Organic matter is one of the major cementing agents for soil aggregates. The size and shape of aggregates give soil a characteristic called soil structure.

Soil structure influences plant growth by affecting the movement of water, air and nutrients to plants.

Sandy soils have little or no structure but are often free draining.

With higher clay content, the soil structural strength increases, but its drainage ability often decreases.

Heavy clays can hold large amounts of water and, as infiltration rates are slow, they tend not to be well drained, unlike sand or loam soils with no or a lower clay content.

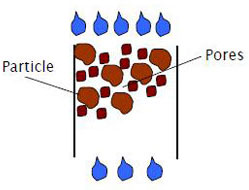

The number of soil pores and the pore size relate to the drainage capacity of the soil. The larger size and fewer the number of pores the easier it is for water to move through the soil profile.

It is not just the soil type that affects structure and drainage but also the activities or environmental factors occurring to them. Root and earthworm activity can improve soil structure through creating large pores. Excessive cultivation, removal of crop residues and increased traffic contribute to soil structural decline, through compaction of soils, reducing pore size and breaking down of soil aggregates.

The chemical make-up of soils also determines structure. When high amounts of sodium are present (>6% exchangeable sodium percentage) clay particles separate and move freely about in wet soil. These soils are known as sodic soils. When sodic soils come in contact with water, the water turns milky as the clay disperses and when the soil dries out a crust is formed on the surface. Sodicity can be overcome by applying gypsum.

Slaking is the breakdown of aggregates on wetting, into smaller particles. Slaking generally occurs when intense rainfall hits dry soil, the aggregates collapse as a result of the pressure created by the clay swelling and the trapped air expanding and escaping. This process can block up pore spaces and when the soil dries a crust is formed, causing infiltration and seedling emergence problems.

Soil colour

Soil colour can indicate the organic matter content of soil, the parent material soil is formed from, the degree of weathering the soil has undergone and the drainage characteristics of the soil.

The colour of the soil is the main indicator of how soils drain.

Table 1: Soil colour and indications

| Soil colour | Indication |

|---|---|

| Dark brown | High organic matter content |

| Black | Humus |

| Red |

|

| Yellow |

|

| Grey, Blue/green hues |

|

Lighter coloured soils can generally indicate low fertility, for example, white sands. While darker soils (like black clays) are quite fertile. There is a large range in between.

Determine soil drainage

The drainage of a soil is an important characteristic to assess, as many plants prefer well-drained soils.

If a soil is poorly drained, sufficient oxygen cannot get to the plant roots, which can stunt or kill the plant.

Soils that are very well drained can limit plant capture of water in drier environments or in dry years due to insufficient water holding capacity.

Other important indicators are:

- texture of the soil

- presence of buckshot and stones

- dispersibility and friability of the soil.

Inorganic component of soils

Inorganic material is the major component of most soils.

It consists largely of mineral particles with specific physical and chemical properties which vary depending on the parent material and conditions under which the soil was formed.

It is the inorganic fraction of soils which determines soil physical properties such as texture. This has a large effect on structure, density and water retention.

Soil texture

The texture of soil is a property which is determined largely by the relative proportions of inorganic particles of different sizes.

In Australia, the following sizes are used to describe the inorganic fraction of soils:

- Gravel — particles greater than 2mm in diameter

- Coarse sand — particles less than 2mm and greater than 0.2mm in diameter

- Fine sand — particles between 0.2mm and 0.02mm in diameter

- Silt — particles between 0.02mm and 0.002mm in diameter

- Clay — particles less than 0.002mm in diameter.

Sand

Quartz is the predominant mineral in the sand fraction of most soils. Sand particles have:

- a relatively small surface area per unit weight

- low water retention

- little chemical activity compared with silt and clay.

Silt

Silt has a relatively limited surface area with little chemical activity. Soils high in silt may compact under heavy traffic. This affects the movement of air and water in the soil.

Clay

Clays have very large surface areas compared with the other inorganic fractions. As a result, clays are chemically very active and able to hold nutrients on their surfaces. These nutrients can be released into soil water to be used by plants. Like nutrients, water also attaches to the surface of clay but this water can be hard for plants to use.

There are many different types of clays. Clays are distinguished from sand and silt by their ability to swell and retain a shape they have been formed into — as well as by their sticky nature.

Soil textural class

The relative proportion of sand, silt and clay particles determines the physical properties of soil, including the texture. The surface area of a given amount of soil increases significantly as the particle size decreases. Consequently, the soil textural class also gives an indication of soil chemical properties.

The exact proportions of sand, silt and clay in a soil can only be determined in a laboratory. However, a naming system has been developed to approximately describe the relative proportions. This classification of soil can be undertaken in the field where particular properties indicate possible textural classes.

To estimate the texture in the field, crush a small sample of soil (10 to 20g) in one hand. After removing any gravel or root matter, work the soil in the fingers to break down any aggregates. With the sample moist but not sticky, the textural class can be estimated by the feel of the sample between the fingers.

Textural class descriptions for soil

A simple way to determine a soil texture and its characteristics is by hand texturing. When texturing soil it is important to understand the behaviour feel, colour, sound and cohesiveness of the soil, which is achieved by making a bolus (wetting the soil and forming a ball). For example, a sandy loam will only just stick together (slightly coherent) and there will be noticeable sand grains which can be seen and felt and heard if you place the bolus close to your ear and squeeze it.

It is then important to form a ribbon from the bolus to determine the clay content of the soil. The longer the ribbon the higher the clay content. The length of the ribbon is measured against a ruler and along with the behaviour of the soil can be compared with the descriptions on the soil texture table. This table will help you to assess soil texture.

Table 2: Guide to common soil textures

| Texture grade | Behaviour of moist bolus (ball formed in palm of hand) |

|---|---|

| Sand | Coherence, nil. Single sand grains adhere to fingers. If you press the bolus between your fingers, holding close to your ear, you will hear the sand grains rubbing against each other. |

| Loamy sand | Slight coherence. Discolours fingers with dark organic stain. Ribbon length 1.0cm. |

| Clayey sand | Slight coherence; sticky when wet. Many sand grains stick to fingers. Discolours fingers with clay stain. Ribbon length 1.0cm. |

| Sandy loam | Bolus just coherent but very sandy to touch. Ribbon length 1.3 to 2.5cm. Can hear sand grains (see Sand description). |

| Fine sandy loam | Bolus coherent. Sand can be felt and heard when manipulated. Ribbon length 1.3 to 2.5cm. |

| Light sandy clay loam | Bolus strongly coherent but sandy to touch. Ribbon length 2 to 2.5cm. |

| Loam | Bolus coherent and spongy. Smooth feel, may be greasy. Ribbon length 2.5cm. |

| Loam fine sandy | Bolus coherent and slightly spongy. Fine sand can be felt and heard when manipulated. Ribbon length 2.5cm. |

| Silt loam | Coherent bolus, very smooth to silky when manipulated. Ribbon length 2.5cm. |

| Sandy clay loam | Strongly coherent bolus sandy to touch. Medium sand grains visible. Ribbon length 2.5 to 3.8cm. |

| Clay loam | Coherent plastic bolus, smooth to manipulate. Ribbon length 4 to 5cm. |

| Silty clay loam | Coherent smooth bolus, plastic and silky to touch. Ribbon length 4 to 5cm. |

| Fine sandy clay loam | Coherent bolus, fine sand can be felt and heard. Ribbon length 4 to 5cm. |

| Sandy clay | Plastic bolus, fine medium sands can be seen, felt or heard in clay matrix. Ribbon length 5 to 7.5cm. |

| Silty clay | Plastic bolus, smooth and silky to manipulate. Ribbon length 5 to 7.5cm. |

| Light clay | Plastic bolus, smooth to touch; slight resistance to shearing between thumb and forefinger. Ribbon length 5 to 7.5cm. |

| Light medium clay | Plastic bolus, smooth to touch, slightly greater resistance to ribboning. Ribbon length 7.5cm. |

| Medium clay | Smooth plastic bolus, handles like plasticine. Has some resistance to ribboning. Ribbon length 7.5cm. |

| Heavy clay | Smooth plastic bolus, handles like stiff plasticine. Has firm resistance to ribboning. Ribbon length 7.5cm or more. |

It should always be remembered that soil texture often varies with depth and that the properties of the topsoil are affected by the properties of the subsoil.

Structure

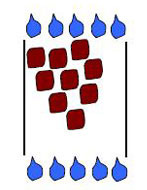

Structure is the arrangement of soil particles and pore spaces between. Soil with a structure beneficial to plant growth, has stable aggregates between 0.5 and 2mm in diameter. Such soils have good aeration and drainage.

Chemical properties

The inorganic minerals of soils consist primarily of silicon, iron and aluminium which do not contribute greatly to the nutritional needs of plants. Those in the clay fraction have the capacity to retain nutrients in forms which are potentially available for plants to use.

Organic component of soil

The organic matter of soil usually makes up less than 10% of the soil. It can be subdivided into living and the non-living fractions. The non-living fraction contributes to the soil's ability to retain water and some nutrients and to the formation of stable aggregates.

Organic matter fraction of soils

The organic matter fraction of soils comes from the decomposition of animal or plant products such as faeces and leaves. Soil organic matter contributes to stable soil aggregates by binding soil particles together.

Plants living in soil continually add organic matter in the form of roots and debris. Decomposition of this organic matter by microbial activity releases nutrients for the growth of other plants.

The organic matter content of a soil depends on the rates of organic matter addition and decomposition. Soil microorganisms are responsible for the decomposition of organic matter such as plant residues. Initially, the sugars, starch and certain proteins are readily attacked by a number of different microorganisms. The more resistant structural components of the cell wall decompose relatively slowly. The less easily decomposed compounds, such as lignin and tannin, impart a dark colour to soils containing a significant organic matter content.

The decomposition rate of organic materials depends on how favourable the soil environment is for microbial activity. Higher decomposition rates occur where there are:

- warm, moist conditions

- good aeration

- a favourable ratio of nutrients

- a pH near neutral

- freedom from toxic compounds.

Soil organisms

The soil contains numerous organisms ranging from microscopic bacteria to large soil animals such as earthworms. The soil microorganisms include:

- bacteria

- fungi

- actinomycetes

- algae

- protozoa

- nematodes.

The diversity of soil organisms can both assist and hinder plant growth. Beneficial activities include:

- organic matter decomposition

- nitrogen fixation

- transformation of essential elements from one form to another

- improvement in soil structure through soil aggregation

- improved drainage and aeration.

Under some circumstances, soil organisms compete with plants for nutrients.

Bacteria are the smallest and most numerous microorganisms in the soil. They make an important contribution to organic matter decomposition, nitrogen fixation and the transformation of nitrogen and sulphur.

The fungi and actinomycetes contribute beneficially to organic matter decomposition. The group of large soil animals includes earthworms, which incorporate organic matter into the soil as well as improve aeration and drainage by means of their channels.

Some soil fungi, nematodes, and insects feed on roots and lateral shoots to the detriment of plants.

Further reading

LEEPER, G.W. and UREN, N.C. (1993) Soil Science, An Introduction. 5th edition, Melbourne University Press.