Deferred grazing

Several types of deferred grazing have been designed to achieve different management targets. The higher the proportion of desirable native species, the more effective the deferred grazing will be in boosting native pasture density and farm productivity.

Optimised deferred grazing

With optimised deferred grazing, the withholding time from grazing depends on the growth stage of the pasture plants, generally from spring to late summer depending on seasonal variations. This deferred grazing starts after annual grass stems elongate, but before seed heads emerge so that the growing points of undesirable annual plants can be effectively removed by grazing. The completion of the withholding time for this grazing strategy depends on pasture conditions of the desirable perennial grasses (seed set, growth and herbage on offer), which are generally ready for grazing from late summer to early autumn. This strategy aims to reduce the amount of seed produced by annual grasses and alter pasture composition, lifting the proportion of perennials while suppressing the annual grasses.

Short-term deferred grazing

Short-term deferred grazing involves no defoliation between October and January each year, aiming to increase soil seed reserves and plant population density. This strategy also allows use of feed in mid-summer when there is generally a feed shortage and may reduce fire risk by grazing long grasses early in summer.

Long-term deferred grazing

Long-term deferred grazing involves no defoliation from October to autumn in the following year (the first significant rainfall event of the autumn/winter growing season). This strategy is used to build up the soil seed reserves and soil moisture and restore ground cover by perennial species. This strategy aims to rehabilitate degraded paddocks with a low percentage of perennial species (e.g. 5–10 per cent) quickly.

Timed grazing

Timed grazing is an alternative form of long-term deferred grazing. It is used to build up the soil seed reserve, restore ground cover and recruit new plants. Pasture is grazed using a large group of sheep greater than 100 sheep/ha, over a short grazing period ranging from 10 to 20 days, depending on paddock size, followed by a resting period from 120 to 130 days. This strategy targets the rehabilitation of significantly degraded paddocks with a very low percentage of desirable species (e.g. ~5 per cent).

Strategic management of pastures can be combined with all types of deferred grazing to deliver the best outcomes. This is often referred to as strategic deferred grazing. For example, onion grass control and fertiliser application can be practised following optimised deferred grazing in an onion grass infested paddock, which may greatly increase the yield and nutritive value of pastures.

Impact of deferred grazing strategies

Deferred grazing addresses several key measures of pasture performance that contribute to the successful rejuvenation of pastures.

Ground cover

Ground cover remains greater than 70 per cent up to mid-January, regardless of grazing treatment applied (Figure 1). However, when a large amount of dead annual grass under set stocking is removed by grazing from January to March, ground cover declines dramatically, before increasing in April/May after rainfall. Ground cover is consistently higher with all deferred grazing regimes due to limitation of grazing over summer/autumn and increased perennial native grass population.

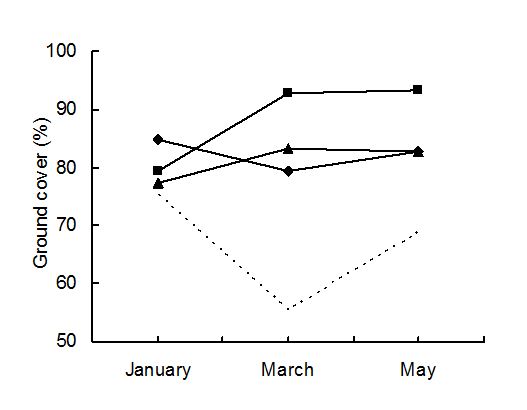

Figure 1. Ground cover over summer/autumn under short-term deferred grazing (■), long-term deferred grazing (♦), optimised deferred grazing (▲) and set stocking (--).

Figure 1 is a graph showing ground cover in percentage during summer to autumn measured in January, March and May for short-term deferred grazing, long-term deferred grazing, optimised deferred grazing and set stocking. Ground cover remains greater than 70 per cent up to mid-January regardless of grazing management. However, when a large amount of dead annual grass under set stocking is removed by grazing from January to March, ground cover declines dramatically to well below 60 per cent, before increasing in April-May after rainfall. In contrast, ground cover for all deferred grazing regimes remains consistently high, close to 80 and 90 per cent, due to limitation of grazing over summer to autumn and increased perennial native grass population.

Plant density

The results from a long-term grazing experiment have shown that deferred grazing regimes significantly increased perennial (predominantly native grasses) and reduced annual grass tiller density (Table 1). However, there were no significant differences in the densities of onion grass, legumes and broadleaf weeds.

Table 1. Mean plant density (tillers or plants/m2) of perennial grass (PG), annual grass (AG), onion grass (ONG), legume and broadleaf weed, under different grazing regimes from a four-year grazing experiment

| Treatment | PG | AG | ONG | Legume | Weed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Short deferred | 8338 | 5396 | 3159 | 630 | 466 |

Long deferred | 9003 | 4713 | 3552 | 460 | 239 |

Optimised deferred | 9998 | 2558 | 3800 | 411 | 245 |

Set stocked | 6245 | 8890 | 4786 | 681 | 248 |

Soil seed reserve

Soil seed reserve is the number of seeds in the topsoil (0–3 cm) measured in autumn. It is an indication of seed production from a grazing system in the previous seasons.

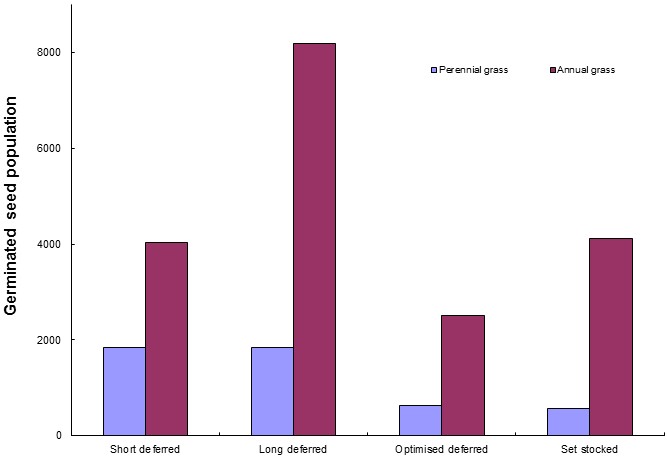

Figure 2. Germinated seed population (seeds/m2) under short-term, long-term and optimised deferred grazing and set stocking.

Figure 2 is a graph showing the germinated seeds per square metre (an estimation of soil seed reserve) of perennial and annual grasses under short-term, long-term and optimised deferred grazing and set stocking. The three deferred grazing systems ranged from 637 to 1850 perennial and 2500 to 8177 annual grass seeds per square meter, whereas set stocking achieved 570 perennial and 4125 annual grass seeds per square metre. Optimised deferred grazing is the most effective treatment to reduce annual grass seed production, with 2500 germinated seeds per square metre.

Seedling recruitment and survival

While deferred grazing dramatically increases soil seed reserve (Figure 2), it is important to know how these seeds, particularly from perennial native grasses, germinate and survive under various grazing systems.

Key:

Each colour indicates seedling density and survival rate for seedlings germinated in corresponding month from May 2009 to April 2010. The absence of January, February and March indicates dry summer conditions where no seedlings germinated.

May: purple

June: mauve

July: yellow

August: light blue

September: dark purple

October: peach

November: blue

December: light purple

April: bright blue

Figure 3. Perennial native grass seedling recruitment (seedlings/m2) and survival under various grazing regimes from May 2009 to April 2010 (starting points in each colour/category represent the population of native grass seedlings that germinated each month and curve represents the change of seedling density over time up to April 2010).

Figure 3 shows the seed germination and seedling survival of native grasses from May 2009 to April 2010 under four grazing regimes – optimised deferred grazing, optimised deferred grazing in year one followed by rotational grazing, timed grazing and set stocking. It is clear that optimised deferred grazing and timed grazing were superior to set stocking both in germinated seedling numbers and seedling survival. At the end of the measurement (April 2010), these two treatments had, on average, 396 seeds germinated and 144 seedlings survived, 9.9 and 5.3 times that of the set stocking. Deferred grazing in year one following by rotational grazing also had higher germinated seed numbers and seedling survival than set stocking, but lower than optimised and timed grazing.

Plant roots and soil properties

Deferred grazing has a profound effect on below ground plant growth. Under deferred grazing, root biomass was increased more deeply in the 0–60 cm soil profile compared with set stocking. With deferred grazing, about 85 per cent of the roots were in the 0–20 cm soil and 15 per cent in the 20–60 cm soil. Under set stocking, over 95 per cent of the total root biomass was in the 0–20 cm soil profile, and less than five per cent was within 20–60 cm profile.

The effect of grazing wet soils is a potential problem for soil health. Stock treading can increase soil compaction and decrease soil porosity and water infiltration. Management options that reverse compaction without cultivation are desirable. Deferred grazing can lower soil bulk density by over 10 per cent by reducing soil compaction from stock treading, leading to increased soil pore size and water movement rate. The growth and subsequent decay of plant roots can enhance the activity of soil organisms, such as earthworms. Deferred grazing systems also increased the soil moisture content of the 0–10 cm topsoil and reduced soil moisture at deeper soil profile, which may contribute to recharge control.

Herbage and animal production

Herbage production under deferred grazing regimes was increased by 19–50 per cent compared with set stocking, two years after deferred grazing regimes were implemented (Table 2). This is a result of increased density and groundcover of perennial native grasses under deferred grazing. An economic analysis on deferred grazing and other grazing regimes revealed that this management strategy can conservatively increase stocking rates by between 25 to 50 per cent within three years on hill country currently carrying less than eight dry sheep equivalent per hectare (DSE/ha).

Table 2. Herbage yield (kg DM/ha) under various grazing regimes

Treatment | Yield |

|---|---|

Short deferred | 4770 |

Long deferred | 3785 |

Optimised deferred | 4083 |

Set stocked | 3183 |

Fertiliser application

Native grasses are adapted to Australia’s low-fertility soils, and some require less fertiliser for production and persistence than exotic species. However, in any grazing system, nutrients that are removed from pasture plants by livestock need to be replaced in the soil to maintain a balance between nutrient export and input. In general, application of some fertilisers such as phosphorus can increase herbage yield, and boost legume growth and pasture quality.

Before applying fertiliser to native pastures, consider the following soil, pasture, livestock production and environmental aspects:

- Soil tests should be performed regularly to determine the current status of key soil nutrients.

- Current and future stocking rates, grazing practices, rainfall and pasture composition need to be considered in determining fertiliser needs.

- Fertilisers that are necessary for improved exotic species can lead to invasion by annual and broadleaf species and a decline in native grass and forb populations.

- Appropriate deferred grazing management, by itself, can increase herbage yield and may outweigh the economic benefit of applying fertiliser; however, nutrients used need to be replaced over time.

- Fertiliser application may have a negative impact on population density and herbage yield of some warm-season (summer growing) native grasses such as kangaroo grass.

- Care needs to be taken when applying fertiliser to paddocks adjacent to waterways and areas of remnant native vegetation. Leave a buffer zone around such areas.

Deferred grazing implementation

To implement deferred grazing strategies effectively and achieve the desired management targets, land managers need to have a clear understanding about pasture composition, growth stage, seasonal constraints and expected outcomes from each of the grazing strategies. These include:

- the proportion of desirable species in the pasture, monitored in early to mid-spring

- the objective of the practice change – whether it is primarily to increase the ground cover or to change the species composition, e.g. increasing perennials and reducing annual species

- requirement for intensive grazing – land-class subdivision and number of livestock

- backup paddocks where stock can be grazed from spring to autumn

- rainfall and length of growing season

- environmental aspiration

- perceived fire risk.

Optimised deferred grazing

Optimised deferred grazing is one of the most effective strategies to alter pasture composition and lift perennial grass population and production while suppressing annual grasses. This method should be used when there is a reasonable amount of desirable perennial species (greater than 20 per cent) in the pasture and the capacity for intensive grazing in spring (e.g. land-class subdivision and stock requirement) is met, allowing for flexibility according to climate and seasonal conditions. The timing of grazing for this method is critical – heavy grazing is required when most annual grass stems have elongated in late winter and early spring (depending on seasonal and regional variations) and before seed heads emerge.

Short-term deferred grazing

Short-term deferred grazing is used to increase soil seed reserves and therefore plant population density, but it will not alter pasture composition as effectively as optimised deferred grazing. This method can be used when intensive grazing is not possible, when there is a shortage of feed in summer and when there is a need to reduce perceived fire risk. The benefit of short-term deferred grazing is to allow plant population density and groundcover to be increased, while in the interim provides time to bring about a long-term whole farm plan (e.g. land-class subdivision and stock requirement).

Long-term deferred grazing and timed grazing

Long-term deferred grazing and timed grazing are used to effectively build up the soil seed reserve, restore ground cover and recruit new plants when a pasture is degraded and there is a very low percentage of desirable species (less than 20 per cent). These methods are expected to raise the desirable native perennials to a level (e.g. greater than 20 per cent) when optimised deferred grazing can be applied.

Strategic deferred grazing

Strategic deferred grazing is designed to control weeds such as onion grass, alter pasture composition and lift perennial grass and legume yield. This method should be used where weeds are a major problem and resources are available to achieve the production targets in a relatively short time.

Pasture maintenance

Outside the deferred grazing periods, it is recommended that rotational grazing based on leaf stage be used to maintain the outputs from deferred grazing. This is because rotational grazing is not only the recommended grazing technique to achieve production and quality targets, but also a grazing regime to maintain seedling recruitment for native grasses.

Leaf stage for grazing

The theory behind ‘leaf stage’ is that the best time to graze a grass plant is when the first regrowing leaf starts to die down. This will effectively reduce pasture decomposition, maintain sufficient carbon reserve in the root system and increase pasture and animal production through optimum tissue turnover and improved nutritive value and pasture utilisation. Different native grasses have a different optimum leaf stage for grazing. Find the most abundant native grass species in the paddock and use the following leaf stage to determine commencement of grazing:

- 3.4 leaves for wallaby grass

- 4.2 leaves for weeping grass

- 3.0 leaves for spear grass

- 3.8 leaves for red-leg grass

- 4.4 leaves for kangaroo grass.

Monitor livestock during grazing

As these deferred grazing strategies may sometimes require high stocking rates of animals grazing dry and lower quality feed, care needs to be taken with the class of livestock grazing these pastures to ensure their nutritional requirements are being met. It is important to monitor the growth of weaner sheep and the condition score of ewes when grazing these pastures. Supplementation of sheep grazing these pastures may be necessary to meet nutritional requirements.

Grazing management strategies summary

A summary of what can be achieved and requirements for individual grazing management strategies are given in Table 3.

Table 3. Effectiveness and requirement of the optimised deferred grazing (OD), short-term deferred grazing (SD), long-term deferred grazing (LD), timed grazing (TG), strategic deferred grazing (STD) in comparison with set stocking (SS) in achieving specific targets

| Management aim | OD | LD | SD | TG | STD | SS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Needs intensive grazing management | Yes | No | No | No | Partial | No |

| Increase ground cover and plant population | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Increase perennials and suppress annual grasses | Yes | Partial | Partial | Partial | Partial | No |

| Increase seedling survival | Yes | Partial | Yes | Yes | Partial | No |

| Effective in perennial plant recruitment | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Effective in building soil seed reserve | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Effective increase of soil organic material | Yes | Partial | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Effective control of weeds (e.g. onion grass) | No | No | No | No | Yes | No |

| Provide feed in summer | Partial | Yes | No | No | Partial | Yes |

| Reduce fire risk | Partial | Yes | No | No | Partial | Yes |

Deferred grazing (DG) quick reference guide

| Type | Aim | Method | Post DG |

|---|---|---|---|

| Optimised | Increase perennial and suppress annual grasses (initial native grass composition greater than 20 per cent) | Graze pasture heavily when annual grass stems elongate and before seed heads emerge. Complete DG in late summer to early autumn | Rotational grazing using native grass leaf stage as a guide |

| Short-term | Use feed in summer while increasing soil seed reserve | Withhold grazing from mid-spring (October) to mid-summer (January) | Rotational grazing using native grass leaf stage as a guide |

| Long-term | Restore perennial plant density | Withhold grazing from mid-spring (October) to autumn break | Rotational grazing using native grass leaf stage as a guide |

| Timed Grazing | Restore plant density of very degraded native pasture (initial native grass composition less than 20 per cent) | Preferably withhold grazing in mid-spring (October). Graze pasture after 120 to 130 days of resting, then repeat for at least a year | Rotational grazing using native grass leaf stage as a guide |

| Strategic Grazing | Combine deferred grazing with weed and fertiliser management | Choose one of the DG strategies. Use the same rule of the DG | Rotational grazing with weed and fertiliser management based on recommendations |