Repairing pugged pastures

When planning to repair pugged pastures consider the following factors.

Bigger picture planning:

- What will you need in the way of feed over the next few months — quality or bulk?

- When will you need this feed — now, summer, next autumn or all of the above?

- How much and what fodder or grain will be available for purchase, if needed?

- At what price will these be available? Prices are coming down but home grown feed, successfully grown, should still be cheaper, and more in your control.

- When to start (depends on soil moisture and temperature, degree of damage, effect of follow-up rains on seed germination, labour or contractor availability).

- Likelihood of late spring to summer rains or will the season 'cut out' early?

Pasture and crop species:

- Cost of seed and fertiliser, contractor rates and availability.

- How were the pastures performing before the pugging occurred?

- If pastures were satisfactory, then restore them to their former glory.

- If not, why not? Was it due to poor soil fertility, poor drainage, weeds? The paddock problem needs to be addressed before or during its rehabilitation to warrant the expense.

- Should the remaining pasture or weeds be sprayed before direct drilling? (Depends on likely competition from the original weeds or ryegrass).

- Medium to severely pugged soils will most likely require some phosphorous (P), potassium (K) and sulphur (S) to be applied at sowing or soon after. Sowing with di- (DAP) or mono-ammonium phosphate (MAP) will supply P and nitrogen (N) at seed germination. Apply N again after first grazing.

- Do not place K fertiliser next to the seed or N at greater than about 20kg N per hectare as these can damage the seed.

- Consider sowing seed treated with Gaucho and fungicides (cereals) as this seems to be beneficial to germination and early growth.

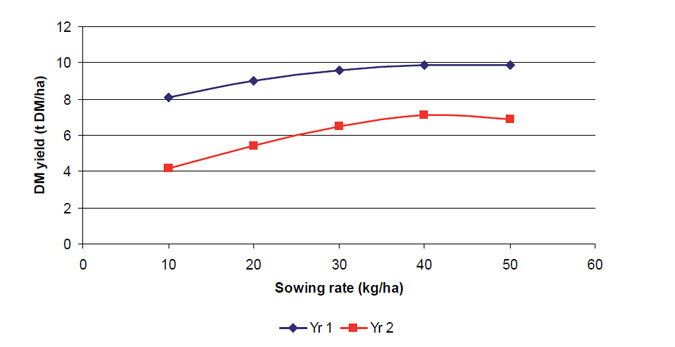

- Project 3030 research has shown that increasing the sowing rate of annual ryegrass in autumn up to 30 to 40kg per hectare has increased the total yield of dry matter production (Figure 1). An extra 680 and 1040kg DM per hectare was consumed (at 80 per cent use of total grown) so economics of increasing sowing rate versus costs can be calculated. This might be worth considering next autumn, even this spring, but will depend on likely follow up rains.

This graph shows the effect of the sowing rate of annual ryegrass on total dry matter production.

Rejuvenation process

- Compare your soil to the Puggology chart: Is the pugging damage light, medium or severe? Some soils recover well — others may need mechanical assistance.

- Can the paddocks get away with minor intervention, for example seed broadcast and harrowed, straight oversowing only more severe and costly actions such as a spray plus powerharrow plus seed dropped on top plus roll or full cultivation plus sowing?

- How much of the farm has been affected? Small areas (less than 5 to 10 per cent of farm) can be handled more easily than moderate (10 to 30 per cent) or very large (above 30 per cent) areas.

- Do some or all paddocks need some levelling or not?

- How will this be done — smudger, roller, harrows?

- What effect will these have on existing pasture — minimal, need oversowing?

- A full cultivation (plough, deep power harrow, mould board) to a reasonable depth (5 to 10cm) in spring will allow the soils to harden up before next winter. Doing this next autumn will result in very soft soils going into winter, delayed pasture growth and risk of damaging both soil and new pastures during late autumn and winter if rain occurs before the initial 1 to 2 grazings.

- Whenever a soil is churned (discing, roterra, power harrow) more soil moisture coming into summer will be lost compared to direct drilling — this is not an issue if the occasional summer shower occurs.

- Double pass (diamond or square) sowing is not an advantage over the traditional single pass sowing.

- Some of the latest seed drills have a row spacing of 100mm which helps substantially with increased numbers of rows per unit area and so a reduction in weed problems, but not totally weed-free.

- 'Sunday' paddocks. That is, the soil in the paddock will be too wet on 'Saturday' and too dry on 'Monday', but is at the best possible on the Sunday — the window for rolling and drilling is often very short.

Which rejuvenation treatment is best?

Over time, the natural processes of most soil will restore its damaged structure and will often repair much of the unevenness left by pugging. However, these processes can be impaired if the weather turns hot before the marks disappear.

If rejuvenation is required, the best treatment is dependent on many factors:

- if the soil conditions are right for the equipment and species or cultivars being used

- good seed or soil contact is achieved

- seeding depth is 1 to 2cm depth

- the follow up weather is favourable, most equipment will usually be satisfactory.

There is very little research on the effect of various pasture rejuvenation treatments for pugged pastures. However, a trial at Taranaki Agricultural Research Station, New Zealand, in the early 1990s, was conducted on a heavy clay loam soil after a single pugging event when the soil was saturated and after a further 13mm rainfall (Table 1).

Table 1. Total ryegrass production (t DM/ha) from the average of unseeded and reseeded treatments over two seasons (1991 and 1992) after a single pugging event

| Treatment | Ryegrass density (No. plants/sq. m) | Pasture production (tonne dry matter/ha) total pasture | Pasture production (tonne dry matter/ha) ryegrass |

|---|---|---|---|

Control (unseeded) | 138 | ||

Harrow only (unseeded) | 134 | 9.5 | 4.2 |

Roll only (unseeded) | 188 | ||

Drill plus harrow (reseeded) | 230 | ||

Broadcast plus roll (reseeded) | 304 | 10.8 | 6.7 |

Broadcast plus harrow (reseeded) | 313 |

Rolling and harrowing alone did not increase pasture production but the three reseeding treatments did — mainly due to the increase in ryegrass from reseeding. Of the 14.5 per cent increase in total pasture due to reseeding, ryegrass accounted for 60 per cent at the expense of Cocksfoot, poa species (winter grasses) and couch (contributing to the Total Pasture in Table 1) in the unseeded treatments. That is, the pugged areas are quickly filled in by unproductive grasses if not reseeded.

This experiment was repeated in 1991 where the pugging was severe but even over the paddock (Table 2). As with the reseeding in 1990, both the drilling and broadcasting gave satisfactory results with harrowing doing a better job of covering the seed than rolling. Although rolling and harrowing alone would have smoothed the paddocks to some extent, pasture recovery was actually depressed.

Note: These are only two examples on a particular soil type.

The pasture responses will vary greatly in any pugging situation depending on factors such as soil type, soil moisture, soil type, seed bed preparation, seed germination, competition from other species and follow up management.

For many severely pugged soils, existing ryegrass will be minimal in many paddocks and the bare areas will be filled by mostly summer weeds and grass species. Some form of restoration will be essential.

Table 2. Results of six treatments to repair pugged paddocks in 1991 after a single pugging event

| Treatment | Ryegrass production (kg DM/ha) summer | Ryegrass production (kg DM/ha) autumn | Ryegrass summer and autumn |

|---|---|---|---|

Nothing done (unseeded) | 1400 | 650 | 52 |

Roll only (unseeded) | 870 | 690 | 37 |

Harrow only (unseeded) | 1200 | 650 | 44 |

Broadcast plus roll (reseeded) | 1230 | 1150 | 60 |

| Broadcast plus roll (reseeded) | 1230 | 1150 | 60 |

Broadcast plus harrow (reseeded) | 1490 | 1330 | Not available |

Drill plus harrow (reseeded) | 1720 | 1220 | 61 |

What about sub-soiling?

Sub-soiling, sometimes referred to as aeration or ripping, can speed up the recovery of soil structure by lifting and cracking compacted layers in the soil. This creates a network of interconnected soil pores which allows vital air and moisture to flow more freely through the soil profile. This means deeper root growth and the build up of soil biota populations again.

- Before sub-soiling, examine the soil profile to identify the presence of compaction zones.

- Push a penetrometer (Figure 2), a pointed steel rod with a T-piece on top for a handle into the ground and feel for a hard layer in the profile. Alternatively, dig a hole to a depth of about 50 cm to determine if a compacted layer exists.

- Dig or push the penetrometer through the compacted layer to determine if water is able to move down the profile, once cracked.

Other possible indicators of a compacted layer are:

- the presence of plant roots or water just above or within the compacted zone

- a lack of large soil pores that may have a bluish-grey colour, indicative of long term waterlogging

- a lack of roots and earthworms.

However, to properly improve water movement through the whole profile, soil below the depth of subsoiling should be well drained, especially on flat areas with poor underlying drainage. If not, the zone of waterlogging becomes deeper and can be even more detrimental to vehicles and animal movement and may be prone to severe re-compaction.

Subsoiling should be done in the spring or autumn when soils are moist, but not too wet.

Set the depth of subsoiling to just below the compacted layer. The soil should be seen to be lifting slightly as the machine is pulled through the soil.

Cracks should be forming from the sub-soiler foot area in an inverted triangle to the surface.

What about aeration?

You can use machines with spikes to aerate soils to a depth of around 20 to 30cm. However, research results have varied — some soil types and specific situations show a response, while others show minimal or nil responses. Use your own experience or that of local farmers to see how soils recover after a wet winter.

Even if you use subsoiling or aeration, it is crucial that you sow seed in most pastures with medium to severe damage for the pasture to make a full recovery.

Acknowledgements

This information was originally written by Frank Mickan, Ellinbank.

July 2011.