Pneumonia in sheep

Dr Joan Lloyd, Joan Lloyd Consulting

Dr Joan Lloyd recently presented in the series of BestWoolBestLamb and BetterBeef roadshows in regional Victoria. She has also presented at a BestWoolBestLamb conference on arthritis.

Pneumonia

Sheep and other ruminants are anatomically predisposed to pneumonia through the rumen pressing on the diaphragm, resulting in shallow breathing.

Pneumonia and pleurisy in sheep are referred to as Ovine Respiratory Complex or ORC for short. Pathogens commonly involved in ORC include the bacteria Mycoplasma ovipneumoniae, Mannheimia haemolytica and Pasteurella multocida, and two viruses, Parainfluenza-3 virus and Respiratory syncytial virus.

In Australia, ORC is often called Summer Pneumonia. Marking, weaning, hot dry weather, raised dust, summer storms, the first shearing and grain feeding can be stressful for lambs, contributing to outbreaks of the disease.

How common is it?

An abattoir survey of ORC pathogens funded by Animal Health Australia and Meat & Livestock Australia was completed in March 2022. Twenty-four abattoir visits were conducted between October 2020 and December 2021, with 1,095 samples collected from diseased ovine lungs. The samples represented 253 abattoir lots, including 182 lots of lambs and 71 lots of adult sheep. Across all the abattoir visits, 64.4 per cent of sampled abattoir lots tested positive for Mycoplasma ovipneumoniae.

Mycoplasma ovipneumoniae was first isolated from two large sheep flocks in southern Queensland in the 1960s that had shown poor growth rates and reduced exercise tolerance for some years. Mycoplasmas are a type of bacteria. Infection with Mycoplasma ovipneumoniae predisposes sheep to secondary lung infection with other bacteria such as Mannheimia haemolytica and Pasteurella multocida that normally live in the nose and throat without causing any harm.

Once in the lungs these bacteria grow and secrete toxins that cause inflammation and lung tissue destruction. All breeds of sheep are susceptible to infection with Mycoplasma ovipneumoniae. Infection persists in a flock in chronic carrier ewes and rams, with infection passing from ewes to lambs soon after birth. Ewes shed the bacteria from their nose and throat, as well as in their milk.

Symptoms

Infected ewes and rams may show no outward signs of infection, or may be coughing, wheezing, have runny eyes, breathe heavily after exertion or simply be found dead. Lambs may begin showing signs of infection (wheezing, coughing, runny nose, runny eyes, difficulty suckling) from one to two months of age.

Some lambs may develop swelling of the carpal (knee) joints. Obvious signs of clinical pneumonia may not be evident for some months until the damage to lungs is much further advanced and the demands on the lungs for oxygen or heat exchange is increased by high summer temperatures or exertion.

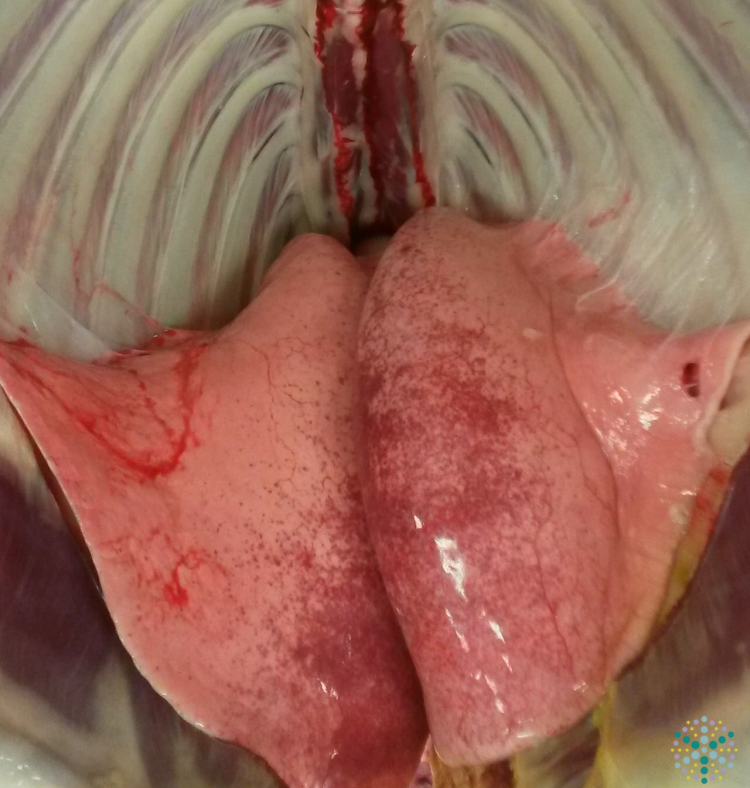

Pleurisy

The pleura is a thin membrane that covers the outside of the lungs and the inside of the chest cavity. When animals have pneumonia, the pleura can become inflamed. Approximately 20 per cent (one in five) sheep that have pneumonia from Mycoplasma ovipneumoniae infection will develop pleurisy.

Pleurisy is a problem in sheep processing plants because it makes it difficult to eviscerate the carcase. Dr Lloyd’s previous research has shown that trimming for pleurisy results in an average one kg per carcase loss to producers.

In addition to lost carcase weight will be the financial penalty to some producers from the trimmed carcase no longer being within specification. Losses are highly leveraged to the processor as high value cuts and the on-floor costs incurred by the abattoir in handing affected carcases.

Diagnosis and treatment

In the 1970s researchers in Victoria suggested that nasal swabs could be a useful way to monitor sheep for respiratory pathogens.

Today, PCR tests and new sample collection technology makes nasal swab monitoring even more useful.

Mycoplasma ovipneumoniae is often introduced onto a farm with newly purchased animals. Testing for Mycoplasma ovipneumoniae and/or asking questions about the infection status of newly purchased animals can help to stop spread onto the farm.

The PCR test developed for the abattoir survey and the innovative Genotube Livestock Swab for collecting PCR samples from livestock is a good way to screen newly purchased animals. Collecting nasal swabs from sheep is straightforward and farmers can collect samples themselves.

PCR testing costs less than $200, which is a good investment compared to the cost of controlling summer pneumonia in infected flocks. Samples can be tested individually or in pools of up to five samples.

When detected early, infection with Mycoplasma ovipneumoniae can be treated. Chronic infections are more difficult to treat. Treatment requires the strategic use of antibiotics, culling animals that don’t respond to treatment and trying to keep infected and uninfected animals separate.