Lambing – 24 hours to shine

Dr Mark Ferguson and Sophie Barnes, neXtgen Agri International. mark@nextgenagri.com

The survival of a lamb is almost completely determined by its birthweight combined with what happens in its first 24 hours of life. There are long-term strategies that will pay dividends for lamb survival like planting shelter belts, improving pastures and permanent paddock subdivision.

For short-term strategies, the important thing is having a plan and acting early. Even at mating, you have a rough idea of how many lambs are coming and how many are likely to be multiples and you can start your planning. You will be ready to fine-tune the plan when the pregnancy scanner gives you the final results.

The factors that matter

The 3 key factors we are working with are nutrition, shelter and privacy. Each paddock on the farm will have a different balance of these and this will determine which ewes end up getting allocated to those paddocks. Nutrition and privacy are important because they are key factors that keep the ewe on the birth site and the importance of shelter is obvious.

Keeping them on the birth site

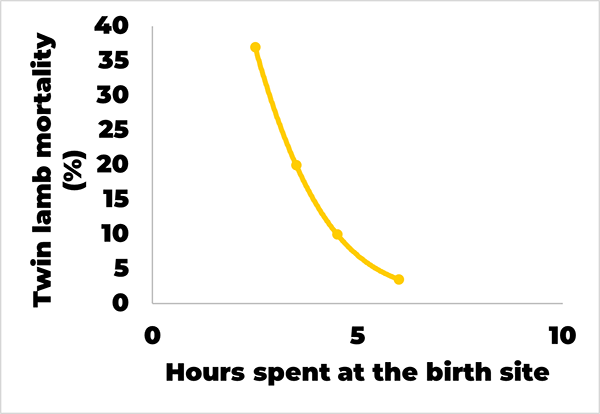

If a ewe stays on the birth site it means there has been no reason to leave it and that means she has formed a strong bond with the lamb and it is highly likely the lamb has had a good feed of colostrum – the elixir of life. The 2 reasons a ewe will leave are she is either hungry or has been disturbed.

Source: Environment and reproductive behaviour, DR Lindsay (Animal Reproduction Science 1996), Elsevier.

Aiming for 1,400-1,500 kg DM/ha of available feed in twin lambing paddocks means ewes can relatively easily consume sufficient pasture without moving too far. Strategies to ensure twin-lambing paddocks have enough pasture in them include deferred grazing, applying urea or gibberellic acid or planting fast-growing fodder crops to either lamb onto or absorb grazing pressure in the time leading up to lambing.

Disturbance is the other key determinant of a ewe moving off the birth site, this disturbance can be from another lambing ewe, a human coming too close or a predator or scavenger approaching. Proximity to human contact is important to consider. Even paddocks with great shelter etc may be the worst lambing paddocks if the school bus goes through the middle twice a day for example.

Their own worst enemy

One of the key disturbances a ewe will endure is from another ewe. The way to minimise this damage is to minimise the number of ewes in a paddock that are likely to be lambing on any given day. This is especially important in multiples and can be achieved through short-term subdivisions. There is no optimum mob size as the smaller it is the better the survival. However, practically there is a limit to how small you can go. A good aim is to have your twins should be stocked at 40-50% of your single mob size, and ideally no more than 100 ewes per paddock for twins.

What goes where

Data from previous years is some of the most beneficial information to have when it comes to lambing paddock allocation. To work out the plan this year, use the historical information to guide some of your decision making. It will differ between farms, but the general rule is that you put the most vulnerable lambs to the best paddock. Ewes pregnant with twins that are a bit light are a higher priority than those the same that are in better condition and both groups are a higher priority than ewes only pregnant with a single lamb.

There is a great T90 (Towards 90) module on lambing preparation which goes through these principles in detail and will help you master the mindset and skills around lambing planning.