Sheep identification

Given my personal involvement during the catastrophic foot-and-mouth disease (FMD) outbreak in the United Kingdom (UK) in 2001, I thought that it might be helpful if I shared my experiences with the readers of Sheep Notes. I will also share my observations of Australia's current National Livestock Identification System for sheep and goats (NLIS Sheep & Goats) that I have attained in my first 12 months in the role of Chief Veterinary Officer.

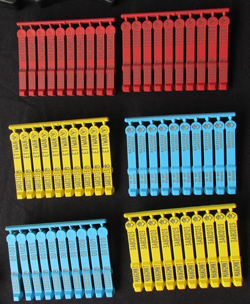

Up until the 2001 FMD outbreak in the UK, keepers of sheep and goats were required to identify their animals with a visually readable ear tag or a tattoo that made it possible to determine which holding they came from (as is the case currently in Australia). They also had to maintain an annual register documenting the total number of sheep and goats present on their holdings.

Keepers provided paper-based movement documentation when sheep and goats were consigned for sale or slaughter. These documents were systematically checked by industry staff at saleyards and abattoirs, and were generally accurate because of the importance to farmers of government subsidies, and the potential financial penalties that were linked to these documents and holding records. Although mixed consignments were often sent from saleyards to abattoirs, they were typically drafted back into their sale lots, and again checked against accompanying movement documentation before slaughter.

Within 2 weeks of detection of the 2001 FMD outbreak, it became apparent that the early dissemination of disease had been due to the movement of infected, but otherwise symptomless, sheep. This occurred before the diagnosis of the index case and the imposition of the national ban on livestock movement, particularly through the large Hexham and Longtown markets (saleyards). Fearful that even more spread had occurred than was identified, because sheep could not be traced, the government organised the systematic slaughter of millions of animals.

In addition, because of the widespread nature of the outbreak, countries worldwide imposed debilitating and prolonged restrictions on the entry of UK livestock, meat and dairy products. The personal impact on beef, dairy, sheep and pig farmers, their families and rural communities was severe and long lasting. More than 6 million animals were destroyed as part of the response to the outbreak.

I have visited Victorian saleyards and abattoirs, which I understand operate in a similar manner to those elsewhere in Australia. For sheep traded through saleyards, my observations suggest that there is limited checking and verification of the traceability information on accompanying National Vendor Declaration (NVD) forms, by either agents or saleyard staff, before animals are sold.

I was surprised to see that the ear tag on sheep often did not identify the vendor, but rather the breeder, and that the property of origin of animals could only be established by linking tag property identification codes (PICs) to PIC information on NVDs. I observed lots purchased for slaughter being mixed after sale. Unlike the situation in the UK, I understand that there is typically no redrafting of sheep or checking of ear tag PICs against movement documents before sheep are accepted for slaughter in abattoirs.

In a recent survey of sheep processed in Victorian abattoirs that had been sourced from Victorian and interstate saleyards and properties, for 44 per cent of all ear tags collected, there was no record of the PIC on the accompanying paperwork. For 41 per cent of PICs listed on accompanying paperwork, there was no record of these PICs being on tags.

My conclusion is that the system for identifying sheep in Victoria, which I understand is similar across the eastern states, is weaker than the system that failed in the UK in 2001.

The view that highly reliable traceability for some parts of the supply chain can compensate for deficiencies in other parts of the supply chain is flawed. Good traceability in lines of sheep sold direct to slaughter does not compensate for the weaknesses that exists in sheep sold through saleyards. This has been shown during real disease scenarios, such as the events in the UK in 2001, an outbreak heavily influenced by the role of sheep traded through saleyards. It is important to note that the FMD outbreak in 2001 was first diagnosed at an abattoir in pigs awaiting slaughter, highlighting the importance of being able to quickly and reliably establish the farms from which animals at abattoirs have been sourced.

The Australian Government's Decision Regulatory Impact Statement (DRIS) on the future of NLIS (Sheep & Goats), published in October 2014, lists recommended enhancements to the current system. The DRIS is clear that, if the current visual tag — based system is to be retained, industry should routinely check at saleyards a selection of sheep from all incoming and outgoing mobs, and the accompanying paperwork. This needs to be complemented by corrective action when errors and omissions are detected. The cost and inconvenience of this approach for saleyard operators, buyers, sellers, transporters and agents will be considerable.

Based on the UK experience in 2001, the notion that marginal improvements to the current system will be adequate is short-sighted. Unless sheep and goats can be traced quickly and reliably, at close to 100 per cent accuracy, during an emergency, the system will fail. Importantly, this means that the benefits of the good traceability systems that we have in cattle will not be realised for cattle producers. By comparison with NLIS (Sheep & Goats), the current Australian electronic NLIS (Cattle) system reports that more than 98 per cent of movements are recorded accurately within 6 hours.

The benefits associated with reliable traceability extend beyond biosecurity and food safety. Reliable identification, and the ability to promptly establish the origins and current locations of sheep and goats have benefits for flock and herd management, and will assist in underpinning Australia's quality brand. Australia's sheep and goat industries will clearly be the major beneficiary of a robust NLIS (Sheep & Goats) system. The beef, dairy and pork industries will also benefit, through a reduction in the duration and impact of disease emergencies.

The key resolution of the conference of Australian agriculture and primary industries ministers (known as AGMIN) in October 2014 in relation to the DRIS reads as follows:

….. that state and territory governments will make necessary improvements to the NLIS, either by enhancing the current mob-based system or by introducing electronic identification (EID), based on analysis of the initial traceability and implementation costs in their jurisdiction. Jurisdictions should also seek to achieve 98 per cent short-run traceability and 95 per cent long-run traceability through ongoing monitoring.

In line with this resolution, all jurisdictions are currently considering how best to improve NLIS (Sheep & Goats) to meet the performance targets agreed by AGMIN. NLIS (Sheep & Goats) is an industry system, with industry responsible for its operation, maintenance and support. The future of NLIS (Sheep & Goats) is an important consideration for all sectors of industry.

Professor Milne was a Divisional Veterinary Manager when FMD was diagnosed in the UK in 2001. He was directly involved in the response to the outbreak, and saw firsthand the impact of the disease on livestock industries and rural communities. The source of this outbreak was a pig farm that was feeding swill (food waste containing meat). Plumes of virus from the pig farm that spread on the wind infected sheep on a property approximately 5 kilometres away. Sheep from this property were traded through saleyards, quickly spreading the disease throughout Great Britain and into Northern Ireland, France and the Netherlands.

Dr Charles Milne, Victoria's Chief Veterinary Officer