Do I need to give selenium or vitamin B12/cobalt to my sheep?

By Lisa Warn (Lisa Warn Ag Consulting)

Whether to supplement sheep with the trace elements selenium or vitamin B12/cobalt is a frequently asked question by producers. Many are using vaccines and drenches that contain these additives without knowing if they are necessary for their sheep or if these short-acting products would be adequate if they did have a deficiency.

Managing the risk of a trace element deficiency in stock is not always straightforward. Even if a region has some soil types that are naturally low in selenium or cobalt, the occurrence of deficiencies in stock can be very sporadic, seasonal, and can be influenced by different pasture species/crops on the farm, fertiliser history or class of stock.

Role of selenium and vitamin B12/cobalt

Selenium is an essential element for animals, but not plants. Selenium is required by sheep for growth and has a role in immune function.

Cobalt is required by rumen microbes to synthesise vitamin B12. Without an adequate supply of cobalt from the soil or feed a vitamin B12 deficiency can occur. Vitamin B12 is important for energy metabolism, protein synthesis and production of red blood cells.

Symptoms of Selenium and Vitamin B12 deficiency are summarised in the boxes.

Marginal selenium and cobalt areas in Victoria

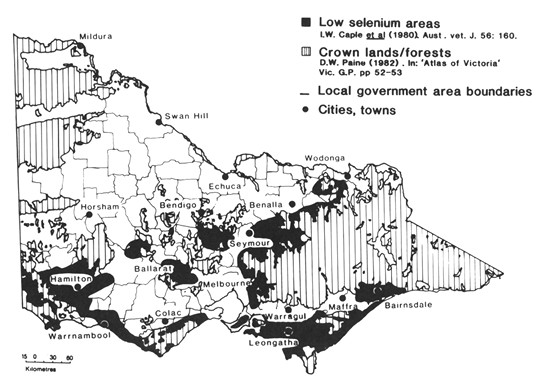

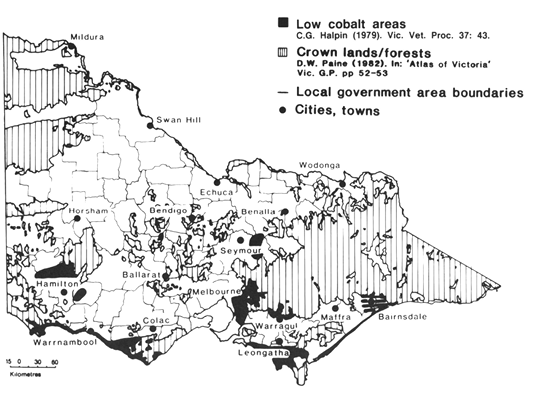

Areas in Victoria at risk of trace element deficiencies in stock or pastures were documented and mapped by the Department of Agriculture in the book “Trace elements in Victoria” by Hosking et al. (1986). Based on available experimental data at the time, the maps show areas where records of livestock blood tests indicated low levels for a trace element or where responses to trace elements had been obtained (Figures 2 and 3).

Risk factors

In the marginal selenium and cobalt areas, rapidly growing lambs and weaner sheep are most at risk. The conditions that can predispose sheep to selenium or Vitamin B12 deficiency are summarised in the boxes.

Diagnosis

Early diagnosis of a disease and treatment are essential to minimise production and stock losses. A veterinarian can help diagnose a selenium or vitamin B12 deficiency by collecting blood samples or post-mortem liver samples for laboratory analysis.

Blood samples can also be taken from weaned lambs (or adult sheep), who are not showing clinical signs of disease, to determine their trace element nutritional status and see if they might be at risk. Plant leaf analysis or soil tests are not appropriate methods to determine the nutritional status of stock.

Recently, the Bairnsdale Bestwool/Bestlamb group undertook a survey of group members flocks to ascertain the selenium and vitamin B12 status. The area is known to be marginal for both (Figures 2 and 3). On each farm, blood samples were taken from lambs (born in late winter/spring 2020) at marking and weaning, before any trace elements were given in vaccines. This work was part of a Meat and Livestock Australia (MLA) Producer Demonstration Site (PDS) project. The results highlighted that 5 out of 10 group members flocks had blood selenium levels considered to be marginal (20–50 GSHPx units) and 1 flock was deficient (less than 20 units). Only one of the 10 flocks had blood vitamin B12 levels that were marginal (200–400 pmol/l). Spring pasture conditions were above average during 2020 to 2021 when the PDS was run.

If blood tests indicate weaner sheep have marginal /deficient levels of a trace element a response trial can be conducted. A definitive diagnosis of a trace element deficiency can only be made from measured improvements in health and production of animals following supplementation compared with a ‘Control’ group with no supplementation.

However, carefully controlled response trials cannot always be conducted on farms and predictions of likely benefits from supplementation may have to be based on information relating production responses to the results of blood tests.

Selenium deficiency

Symptoms:

- Ill-thrift – reduced weight gain and wool growth in lambs.

- White muscle disease – can affect lambs and calves:

- Stiff-legged gait or unable to stand.

- Arched back.

- Sudden death – caused by lesions in heart muscle.

Risk factors:

- Stock class – Young growing stock are most susceptible

- Soil type – sandy or granite soils

- Seasonal variation – lowest levels of selenium in pastures occur in spring and summer.

- Variation between years – white muscle disease in lambs and calves in spring is most prevalent in years when there is good autumn rainfall and abundant clover growth in spring

- Heavy or long-term applications of fertilisers containing sulphur (eg.superphosphate or gypsum) decrease the concentration of selenium in pastures and may also decrease the uptake of selenium by livestock.

Pasture type – Clover dominant pastures – clovers have lower Se concentrations than grasses.

Vitamin B12/Cobalt deficiency

Symptoms:

- Reduced appetite and growth rates

- Diarrhoea

- Weeping ‘rheumy’ eyes

- Anaemia

- Scaly ears (Affected sheep show signs of photosensitization associated with liver damage).

Risk factors:

- Stock class – Young growing stock are most susceptible. Lambs are more susceptible than calves.

- Soil type – coastal calcareous sands, sandy or well drained soils.

- Seasonal variation – cobalt in pastures and plasma vitamin B12 in livestock is lowest in spring.

- Variation between years – seasons favouring lush pasture growth favour development of cobalt deficiency. This is due to animals ingesting less soil when grazing lightly stocked, rapidly growing pastures. Soil provides a more concentrated source of cobalt to the ruminant than pastures.

Pasture type – Grassy pastures – grasses have lower Co concentrations than clovers.

Preventative treatment options

Selenium (Se) is available by injection either alone or in combination with vaccines or drenches, as is vitamin B12 (but as cobalt (Co) in drenches). Se and Co are also available in rumen pellets which can be given to lambs at weaning and can last for 3 years.

In low Se areas, lambs can be treated with a Se injection at marking and weaning. Short-acting forms of Se found in vaccines can give 6–8 weeks protection. The need for any follow up treatment, or the need for a longer-acting Se injection (18 months protection) at marking or a selenium rumen pellet at weaning, will depend on the extent of the deficiency/risk period and the age that the lambs are kept.

In Victoria, no responses to selenium treatment have been observed in adult sheep. However, if pregnant ewes are deficient, they can be treated with a short-acting selenium injection 4 weeks before lambing so that lambs are protected from white muscle disease in the first few weeks after birth.

In low cobalt areas, lambs can be treated with a vitamin B12 injection at marking and weaning. Short-acting forms of vitamin B12 in vaccines or separate injections can give up to 6–12 weeks protection, depending on the extent of the deficiency. There are no long-acting B12 injections available in Australia. The need for any follow up treatment or the need for a cobalt rumen pellet at weaning will depend on the extent of the deficiency/risk period. If ewes are deficient, they can be treated with a vitamin B12 injection before lambing to ensure adequate vitamin B12 reserves in the foetal liver and colostrum.

The addition of Se to a 6 in 1 vaccine increases the cost by around 5 c/dose while the addition of vitamin B12 increases the cost by around 40 c/dose (nearly double the cost of the vaccine). A separate vitamin B12 injection costs around 8c/dose (lamb dose) so is a cheaper option if it is needed but requires the extra labour/time for a separate injection. A long-acting Se injection can cost 30c/dose (lamb) to 60c/dose (adult). In severely deficient areas where use of rumen pellets may be an option at weaning, the cost is around 90c for a selenium pellet (with a grinder), $1 for a cobalt pellet (and grinder) or $1.50 for a Se and Co pellet.

Seek advice

If you are uncertain about whether your stock may be at risk of certain trace element deficiencies it is important to seek expert advice from your veterinarian or animal health advisor. They can diagnose if selenium or vitamin B12, or both, is an issue or not and if so then work out which product/s will supply the required trace elements to cover your main risk period, most efficiently and at lowest cost.

For more information about the MLA PDS ‘Managing trace elements in sheep’ visit the MLA website.

Thank you to Dr Dianne Phillips and team at Agriculture Victoria, for collecting the blood samples for the MLA PDS project.