A mix of tools to make the best of the good years and ride out the tough ones

- Property: Sandalwood

- Owners: Barry and Kristina Mudge

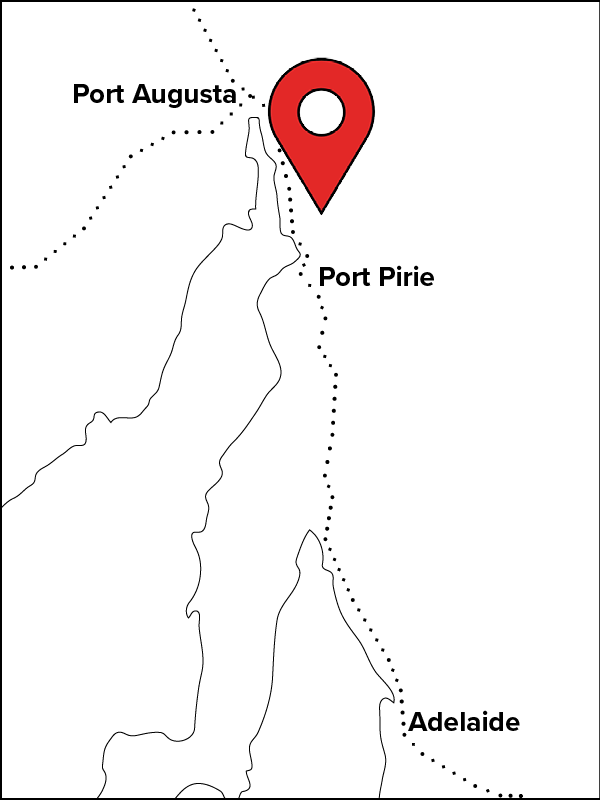

- Location: Upper North of South Australia

- Farm Size: 1600 hectares (1200 hectares cropping)

- Average Annual Rainfall: 330 mm

- Soil Types: loamy mallee, stoney red-brown earths and desert loams

- Soil pH: 6.8 to 8

- Typical Crops Grown: wheat, barley, lentils and vetch pasture

Barry and his wife, Kristina, operate a 1600 Ha mixed farming property in the Upper North of South Australia. Rainfall is highly variable, but the annual average is around 330 mm (220 mm growing season). Barry considers the variability in rainfall an asset which needs to be managed to maximise profitability over the range of seasons.

'The facts are that in these low rainfall environments, we can either be farming in some of the most productive country in the state, or some of the worst, depending on how the season turns out. The challenge is to maximise the benefits of the good years and just learn to ride out the poorer seasons.'

So, the focus needs to be on good agronomy and maximising water use efficiency. At the same time, Barry believes that seasonal forecasts have a role to play, but he remains cautious about putting too much emphasis on them. He has used seasonal forecasts in various ways over a lot of years but points to the need to be realistic in what they are telling us.

'We are very fortunate in Australia to have comprehensive climate records dating back at least 100 years. This provides us with an excellent starting point in understanding what the variability of our seasons looks like - all a seasonal outlook forecast does is potentially alter the probabilities of the various outcomes occurring. And, unfortunately, history shows that the reliability of seasonal forecasts is not particularly high.'

A key time of the year for decision making is when crops are established; usually in late April or early May. Several years ago, Barry developed a simple index to provide guidance on expectations for the season which was then used to guide planting intentions. While seasonal forecast information was included in the index, it remained a relatively minor influence.

'Generally, the information that we know about the season, such as stored soil water, crop establishment opportunities and other agronomic factors remain more critical to the decision than a forecast whose reliability is marginal at best.'

If seasonal forecasts are going to be considered, Barry considers that we firstly should focus on the level of skill sitting behind the forecast. And this can obviously vary both at different times of the year and between different years.

'I get annoyed when I see a forecast that hasn’t got at least some reference to skill, or past reliability. As an example, anyone can forecast the winner of the Melbourne Cup, but history shows that not many people actually get it right.'

While Barry believes his planting index was useful in getting an early feel for the season, he has been disappointed with the reliability of the early season forecasts.

'From my observations, rarely do we get any useful information in our district from seasonal forecasts prior to June. This is a great pity as this could be incredibly valuable. But as we progress into winter and spring, we can get some years where there are clear indications of trends. This might only occur, perhaps 50 per cent of the time but it can prove useful in adjusting fertiliser levels or planning fungicide applications.'

Barry’s main message when using seasonal outlook forecast information is to make sure that any influence they may have on decision making is soundly based.

'Too often we tend to allow forecasts to subjectively invade our sub-conscious and affect our decision making. A little bit of analysis of the range of possibilities and how a seasonal outlook forecast could change these is usually a worthwhile exercise.'

An example of this occurred in 2018. Towards the end of his sowing program, Barry had the choice between continuing to plant lentils (seen as relatively risky in his low rainfall environment) or planting vetch for grazing (seen as less risky). Some analysis showed that it was only in very dry years would the vetch be the better proposition and a seasonal forecast would need to be showing extreme dryness with a high level of underlying skill to support the argument to plant vetch.

Given the uncertainties inherent in the climate, Barry considers it unlikely that reliability of seasonal forecasts will ever reach the stage when they become the 'Holy Grail'.

'We accept that we farm in a highly unreliable and climatically variable region. Seasonal outlook forecasts will not change this. But used cleverly, they may sometimes enable us to be at least more comfortable with the many climate sensitive decisions that we need to make in the course of our farming careers.'