Seasonal tools fine-tune investment

For Greg Toomey from Landmark Elmore, the art of risk management is a delicate balance that sees him continually fine-tune farm business decisions to match variable and changing seasonal and climatic conditions.

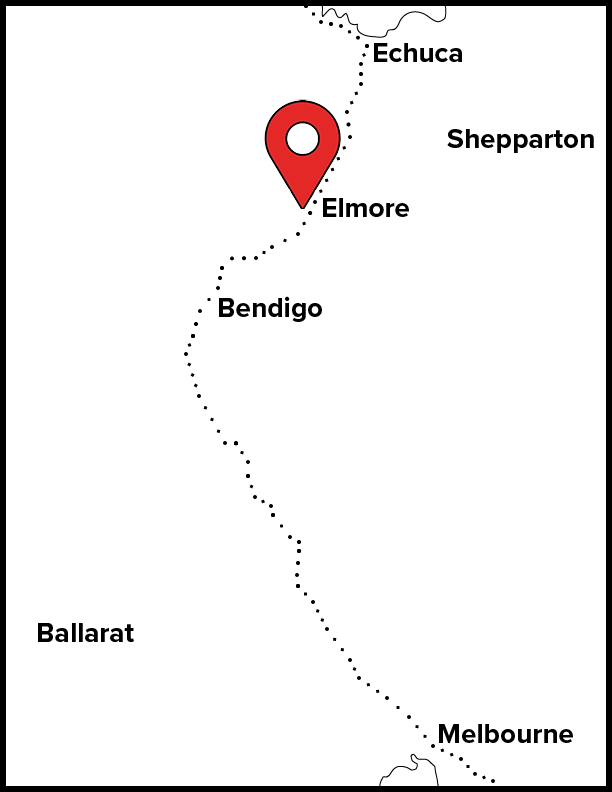

Drawing on 30 years of agronomy experience, including 19 years as an Elmore district agronomist in northern Victoria, Mr Toomey aims to lift gross margins while shielding cropping operations from shifting, sometimes harsh, weather patterns.

With profitability front-of-mind, he uses experience and trusted sources of information to guide 'clever investment' in cropping inputs that help optimise gains in bumper years and minimise losses in challenging years.

Informing this approach to crop investment, Mr Toomey refers to an increasingly sophisticated suite of seasonal and climate risk management tools developed by Agriculture Victoria.

The suite comprises subscription-based seasonal forecast commentary, The Break, which is produced by Agriculture Victoria. The Break provides a range of seasonal forecast summary newsletters, comparing forecast models and soil moisture data for 3 to 6 months.

Mr Toomey examines deep soil moisture probe data and commentary released by Agriculture Victoria, who manage a Victoria-wide network of probes on growers’ properties.

He also refers to Bureau of Meteorology (BOM) data, particularly in terms of its local and state seasonal forecasts, Indian Ocean Dipole and Southern Oscillation Index monitoring, Australian weather watch radar and wind forecasts.

Exploring how he wields these tools for northern Victorian growers, Mr Toomey uses soil moisture probe data as a 'reference point to help extrapolate plant available moisture across a cropping district'.

Accompanied by a weather station, sensors in the capacitance probes record subsoil moisture from a fixed location on farms at 10-centimetre increments from a depth of 30cm to one metre in the soil profile. The data, which can be accessed by agronomists and other growers, is then sent via the mobile phone network to a server for storage, analysis and interpretation using graphing software.

Mr Toomey says trends in the soil moisture data gleaned from the on-farm probes are used to 'tweak' the percentage mix of crops grown in rotation.

For example, information from the probe network that ‘suggests subsoil moisture is depleted often provides a cue to reduce the farm area planted to canola.

The farm area planted to this deep-rooted oilseed crop, known to access moisture at depth in the soil, is generally replaced with relatively drought-tolerant barley or oaten hay crops, he says.

Mr Toomey says the probe network has also delivered unexpected, and influential, new perspectives on crop water-use.

In the wet 2016 season in the Elmore district, for instance, the on-farm probes indicated the soil moisture profile was full in early October but, by the end of that month, crops had used more than 80 per cent of this moisture reserve, he says.

As a consequence of this finding, Mr Toomey now more conservatively estimates crop yield potential in spring which, in turn, means applying less nitrogen fertiliser and reduced expenditure on crop nutrition.

He also measures seasonal forecasts, mainly in winter and spring, against soil moisture data as part of an overarching strategy that aims to match crop inputs to growing season conditions and ultimately maximise farm business profitability.

Seasonal forecasts are studied against the backdrop of BOM forecasts, particularly Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD) and El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) climate indicators distributed by Agriculture Victoria, he says.

For instance, he might apply more nitrogen to feed higher yield potential where climate forecasts suggest negative IOD and La Niña phases, which are indicative of above-average winter and spring rainfall, and colder-than-average temperatures.

A forecast for wet, disease-prone conditions can also influence the timing of, and planned expenditure on, fungicide applications, he says.

Whereas predictions of positive IOD and El Niño phases associated with dry, warm conditions, might provide a trigger for cutting crops for hay.

Putting the potential profitability of this management decision into context, he says that in many situations, cutting northern Victorian crops for hay secured an extra $500 per hectare compared with harvesting them for grain in the dry 2018 season.