Field diagnosis of honey bee brood diseases

It is important for beekeepers to quickly identify the 4 serious bee brood diseases:

- American foulbrood

- European foulbrood

- chalkbrood

- sacbrood.

Apiarists are encouraged to:

- submit samples for laboratory confirmation

- seek advice from our apiary officers.

Inspection of brood

People inexperienced in handling bees and collecting samples should read Safe beekeeping practices first.

Thorough inspections of brood should be conducted in both:

- early spring during the main honey producing season

- in autumn when hives are prepared for winter

Look for any unusual cell caps and brood, especially larvae that are off-colour or abnormally positioned in the cell.

Definitions

- Brood — eggs, larvae and pupae found in the cells of the combs in the broodnest.

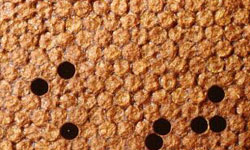

- Larvae — curled white grubs found in open cells of brood combs. At first, they look like a very small letter 'C', positioned at the base of the cell. They grow to almost fill the cell (Photo 1). After the cell is capped, the larvae lie on their backs, each on the lower wall of its cell.

- Pupae — the intermediate stage in the development of the bee from larva to adult. During this stage, the larva gradually changes to the adult.

- Caps — caps placed by the bees to seal cells containing pupae or honey. The caps over brood cells are usually cream, light brown to brown, or tan.

- Brood pattern — a good brood pattern occurs when nearly all the cells in a given area of comb contain brood. A poor or irregular brood pattern has a scattered arrangement in which there is a considerable mixture of empty, open and capped cells.

- Scale — dried, decomposed remains of a larva or pupa.

- Tongues — the tongue, formed during the pupal stage of the bee's life-cycle, does not decompose when infected with American foulbrood. It protrudes upwards from the scale towards the roof of the cell.

A healthy brood

A healthy brood

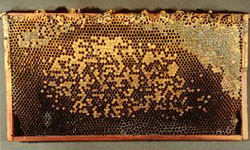

The general appearance of the brood pattern is regular with no dead larvae or pupae (Photos 1 and 2).

Caps are uniformly brown, tan or cream. Each cap is slightly raised or convex, without any holes, except in a few cases where the cell cap has not yet been fully built.

It is always good to look inside cells with perforated caps to make sure the developing bee is healthy.

It is always good to look inside cells with perforated caps to make sure the developing bee is healthy.

Larvae are glistening and pearly white, with an orange gut line running along their back. Healthy pupae under the caps are at first white but as they develop into adults, their colour darkens. The eyes begin to colour first.

American foulbrood (AFB)

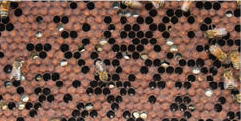

At first, AFB is slow to establish and only a few larvae will be affected. In advanced cases the brood pattern will be irregular (Photo 3). The absence of an irregular brood pattern does not mean the disease is absent.

At first, AFB is slow to establish and only a few larvae will be affected. In advanced cases the brood pattern will be irregular (Photo 3). The absence of an irregular brood pattern does not mean the disease is absent.

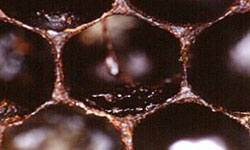

Infected larvae and pupae, die after their cells have been capped. Adult bees may later partly or totally remove the caps, and as a result the caps may be perforated (Photo 7).

They may also be sunken, concave, dark and at times greasy-looking.

Diseased larvae and pupae always lie stretched out on their backs on the lower wall of their cells.

Diseased larvae and pupae always lie stretched out on their backs on the lower wall of their cells.

If the cell opening is compared to a clock-face, the diseased individuals (and later scales) will be positioned at the bottom of the face between the figures 5 and 7.

The colour of dead larvae and pupae is at first dull white, then light brown, later coffee-brown and finally black.

The moist, decaying remains of a dead larva in a cell may be 'roped out' with a match to 25mm or more (Photo 4). The match is inserted into the larval remains which are then gently picked up (or gently scooped) to be slowly withdrawn. The tacky remains can usually be withdrawn from the cell again and again.

The moist, decaying remains of a dead larva in a cell may be 'roped out' with a match to 25mm or more (Photo 4). The match is inserted into the larval remains which are then gently picked up (or gently scooped) to be slowly withdrawn. The tacky remains can usually be withdrawn from the cell again and again.

The remains slowly dry to form dark-brown or black scales (Photo 6). In dull light, the scales, being dark, are not easily seen.

It is best to hold the frame with the top bar held towards your stomach and tilted to allow sunlight to fall directly onto the lower wall of the cells.

Dried scales do not rope out with the matchstick test. Unlike scales of other brood diseases, they firmly adhere to the cell wall and are impossible to remove without damaging the cell.

Dried scales do not rope out with the matchstick test. Unlike scales of other brood diseases, they firmly adhere to the cell wall and are impossible to remove without damaging the cell.

In some outbreaks, tongues of dead pupae may be seen projecting from the remains almost up to or even touching the roof of the cell (Photos 5 and 6). The presence of tongues is a very reliable AFB field sign.

The absence of tongues is not an indication that AFB is not present in a hive.

Fully-formed bees that have died just prior to emerging from their cells may be observed with their tongue exposed. This is not a sign of AFB.

Odour or smell is not a reliable diagnostic tool because some cases of AFB have no discernible smell at all.

Odour or smell is not a reliable diagnostic tool because some cases of AFB have no discernible smell at all.

European foulbrood

Larvae infected with European foulbrood are mostly affected while they are curled and before the cell is capped.

In cases where larvae die after their cell has been sealed, the cap may be perforated (Photo 7), sunken, concave and dark.

Dead larvae are twisted in their cells (Photo 8) and may be positioned on the upper, lower or side walls of the cell. Their colour turns to off-white, yellow, then brown and sometimes black.

Dead larvae are twisted in their cells (Photo 8) and may be positioned on the upper, lower or side walls of the cell. Their colour turns to off-white, yellow, then brown and sometimes black.

Freshly dead larvae have a soft and watery consistency, which soon becomes pasty. The scales are tough and rubbery but may become brittle. They are found in any position and, unlike AFB, are easily removed from the cells.

Often the disease spreads quickly in the hive and an irregular brood pattern may soon be noticed in advanced cases.

Older larvae killed by this disease lie stretched out on the lower walls of their cells very similar to those killed by AFB.

Older larvae killed by this disease lie stretched out on the lower walls of their cells very similar to those killed by AFB.

When the matchstick test is used, the remains will stretch — sometimes to about 18mm but usually much less. The remains will usually only stretch once or twice and thereafter cannot be drawn out from the cell.

A laboratory diagnosis may be needed to confirm which disease is present.

As with AFB, odour is not a reliable method of diagnosis because often there is no odour present.

As with AFB, odour is not a reliable method of diagnosis because often there is no odour present.

Chalkbrood

Larvae infected with this fungal disease die about two days after their cells have been capped. Infected larvae lie stretched out on the cell walls, similar to AFB infected larvae.

Fungal growth (mycelia) first occurs in the gut and then appears externally at the rear end of the larva. Later, the whole larva is covered with the white fluffy growth.

Fungal growth (mycelia) first occurs in the gut and then appears externally at the rear end of the larva. Later, the whole larva is covered with the white fluffy growth.

The larva swells and takes on the hexagonal shape of the cell. It then dries and shrinks to a hard chalk-like, flattish, ‘mummy’, or scale, which is either white or dark blue-grey to black (Photo 11). These are easily removed from their cells and may even rattle when the comb is shaken.

The cell caps may be perforated or entirely removed by the bees. In advanced cases, the brood pattern will be irregular, interspersed with open cells containing mummies.

In advanced infections, mummies may be seen deposited by the bees on the floor of the hive and immediately outside the hive entrance (Photo 12).

Sacbrood

Larvae infected with sacbrood virus show disease symptoms after the cell has been capped.

The larvae lie stretched out on the lower walls of their cells, similar to that of AFB. Grey, almost clear granular fluid accumulates between the skin and the body of the larva, causing a sac-like appearance, hence the name 'sacbrood'.

The larvae lie stretched out on the lower walls of their cells, similar to that of AFB. Grey, almost clear granular fluid accumulates between the skin and the body of the larva, causing a sac-like appearance, hence the name 'sacbrood'.

Infected larvae become 'gondola' or 'banana' shaped with the head raised towards the top of the cell opening (Photo 13).

They change from glistening white to grey or pale yellow, later turning brown and finally black. The head usually blackens first.

Caps may be perforated or totally removed. An irregular brood pattern may occur in advanced cases. Infected larvae dry to a flattened, gondola-shaped scale that darkens with age (Photo 14). The scales are easily removed from the cell, unlike AFB.

Caps may be perforated or totally removed. An irregular brood pattern may occur in advanced cases. Infected larvae dry to a flattened, gondola-shaped scale that darkens with age (Photo 14). The scales are easily removed from the cell, unlike AFB.

Further information

If you require further information or assistance, please contact the Customer Service Centre on 136 186 or email honeybee.biosecurity@agriculture.vic.gov.au