Benign theileriosis in Victoria

Benign theileriosis is a tick-borne disease caused by intracellular blood parasites belonging to the Theileria orientalis group.

The buffeli genotype or variant of the T. orientalis group has been incriminated as the cause of benign theileriosis in Victoria, and other parts of Australia, over a number of years. The infection has been shown to be endemic and virtually asymptomatic in Gippsland over a period of time.

More recently, other variants of the T. orientalis group have been implicated in episodes of clinical disease.

During 2011, a number of cases of benign theileriosis were reported in Victoria outside the endemic area in naïve cattle herds where relatively high case fatality rates have been reported. These cases were often associated with the introduction of animals from endemic areas interstate. Similar outbreaks of theileriosis have been reported from non-endemic areas of New South Wales in recent years. There has been some association with high rainfall, increased tick activity and cattle introductions.

Benign theileriosis has been detected in all states and territories of Australia except Tasmania and South Australia.

Aetiology

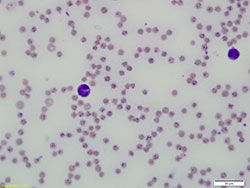

Benign theileriosis is caused by protozoal parasites belonging to the Theileria orientalis group. The protozoan mainly infects erythrocytes of mammalian hosts (Figure 1).

When an infected tick feeds, sporozoites are transmitted in saliva and injected into the host's bloodstream. Following sporozoite inoculation, schizonts can be detected transiently in lymph nodes, spleen and liver but these do not appear to play a major role in the pathogenesis.

In the life cycle of benign Theileria forms, schizonts do not develop in lymphocytes and do not induce transformation and fatal lymphoproliferation.

The form of parasite within the erythrocyte is known as a piroplasm. Piroplasms appear in the erythrocytes approximately 10 days post-inoculation resulting in a transient fever and regenerative anaemia. In immunologically intact animals, parasitaemia is generally low and animals recover from the infection but the parasites can persist, presumably for life, occasionally causing a relapse particularly under stressful conditions such as:

- pregnancy

- lactation

- rapid changes in environmental conditions.

Piroplasms are ingested by ticks sucking blood from infected cattle and undergo further stages of their life cycle in the gut and salivary glands of the tick vector.

There are multiple 'variants' or genotypes of the parasite, including:

- chitose (type 1)

- ikeda (type 2)

- buffeli (type 3).

The ikeda and chitose types have been the predominant genotypes associated with clinical disease recorded in recent years in both Victoria and New South Wales. The buffeli type has generally not been associated with clinical disease in Australia.

Vectors

The vectors of benign theileriosis in Victoria are believed to be ticks of the genus Haemaphysalis, mainly H. longicornis, the bush tick.

The engorged adult female bush tick is oval in shape and about the size of a pea, with red to reddish-brown legs (Figure 2). Both larvae and nypmphs are very small, and are not easily seen with the naked eye.

H. longicornis is a three-host tick — each of the three life cycle stages (larva, nymph, adult) — must attach to a host for a few days before continuing development. The adult ticks fall to the ground after engorging on the host to lay a few thousand eggs.

Theileria spp. transmission in the tick is stage-to-stage (trans-stadial). In other words, if a larva or nymph ingests the parasite from an infected animal, then the following developmental stage will transmit the parasite to the next animal it feeds on. Trans-ovarial transmission (from an adult female tick via its eggs to the next generation) does not occur.

Each developmental stage spends only a few days on the host before detaching and dropping to the ground.

The life cycle of H. longicornis takes about 12 months. Adult ticks are seen mainly during early summer — larvae from late summer to early winter —nymphs, mainly in spring. Eggs are able to overwinter on pasture. Larvae are also known to survive winters.

Bush ticks are environmentally sensitive and flourish when conditions are moist for long periods and good vegetation cover exists. Hot dry conditions do not favour its survival and continued reproduction. The fact that H. longicornis prefers moist conditions provides a possible explanation for its apparent spread in Victoria in 2011 after the wet season of 2010 to 2011.

Hosts

Bush ticks are mainly a cattle parasite, but are able to attach to other mammals including wildlife, birds, livestock (including horses, sheep, goats and poultry) and domestic animals such as dogs and cats. In sheep, bush ticks prefer to attach mainly on body parts not covered by wool.

The most common sites of attachment on cattle are:

- around the tail

- on the udder

- inside the legs

- on the brisket

- in the ears

- occasionally on the face and neck.

Although it may cause tick irritation and local reactions in all species, H. longicornis only transmits benign theileriosis to cattle.

Other epidemiological aspects

It appears in most cases that once cattle are exposed to parasites of the T. orientalis group, they develop immunity. Thus calves after about 6 months of age, and adults surviving in mobs with sick cattle, will not usually suffer further disease. In other situations, new cases appear to continue in some herds following an initial outbreak.

In endemically affected areas, clinical disease is rare and usually only seen in new crops of calves and introduced naïve cattle. Clinical disease is more common and severe in non-endemic areas, as there are low levels of immunity in the population. In non-endemic areas, disease is spread from introduced infected cattle.

Clinical signs

Clinical signs are typical for a disease caused by a haemoparasite. Benign theileriosis is characterised by fever, anaemia, tachypnoea, depression, lethargy, jaundice and often eventual death.

Exercise intolerance may be observed.

Pregnant cows may abort and still-births occur. Death rates are often highest in heavily pregnant cows.

In herds confirmed as having benign theileriosis in Victoria in 2011, an average of 2.5 per cent of animals were reported as being clinically affected. Of the clinically affected animals in these herds, up to 32 per cent died. Most animals in affected herds have apparently remained symptomless.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis relies on a combination of clinical signs:

- a PCV below 15 per cent

- evidence of a regenerative anaemia

- demonstration of the presence of the parasite either microscopically or by PCR.

Variants of the T. orientalis group cannot be distinguished morphologically by examination of the blood smear. PCR must instead be used.

Samples that should be collected for diagnostic purposes include:

- blood smears (for parasite identification)

- EDTA blood (PCR and PCV)

- clotted blood (serology).

Treatment

Treatment options for benign theileriosis are limited to supportive care and symptomatic treatment.

There is currently no drug registered in Australia for the treatment of benign theileriosis. Some vets have reported good responses to treatment with oxytetracycline or imidocarb of mildly affected animals when administered early in the course of the disease, but poor responses in severely affected animals. Apart from the obvious unreliability of this treatment, the issue of milk and tissue residues must be borne in mind when considering such medications.

Blood transfusion has been performed occasionally on valuable animals. Animals improve following transfusion but it is expensive and not practical if multiple animals are involved.

Most importantly, stress and movement of affected cattle should be minimised or their reduced ability to transport oxygen throughout the body may lead to collapse. They should be rested, nursed and given high quality feed. Handling of affected cattle should be avoided where possible; if movement or yarding is necessary, move animals slowly.

Control and management

Control and management of benign theileriosis is not without difficulties. No vaccine is currently registered in Australia and many features of the biology and epidemiology of benign theileriosis are poorly understood. For these reasons, control and management are based on a combination of:

- risk management of cattle movements

- general stock management

- tick control.

Despite having followed recommendations for control and management, some producers have experienced significant losses, and the reasons why some herds are more severely affected than others is not clearly understood.

Risk management of cattle movements

Introduction of stock from known affected properties or areas should be avoided where possible.

When introductions take place of cattle with an unknown health status, new arrivals should be inspected for ticks and quarantined from the rest of the herd for a minimum of a month. Quarantined cattle should be held separate from the rest of the herd in paddocks with short vegetation to minimise environmental survival of ticks. Ideally, introduced cattle should be treated with a registered acaricide in accordance with the manufacturer's recommendations prior to departing the property of origin and then upon arrival. If this is not possible, a registered acaricide should be used on introduced cattle found to be tick-infested during the quarantine period. It is important to observe the prescribed withholding periods for treated animals.

Avoid moving cattle, especially late pregnant heifers and cows from areas where cattle have a low chance of exposure to areas where Theileria spp. parasites are commonly found. In areas where Theileria spp. commonly occur, cattle should be sourced locally where possible.

Assess the risk the animal movement poses prior to moving the cattle. A laboratory test confirming the cattle to be moved have been exposed to Theileria spp. (in particular, exposure to the known pathogenic variants) indicates the animals would be expected to have a low risk of developing disease on moving to endemic areas.

Inspections during high risk periods

In endemic areas where most adult cattle are likely to be immune, calves should be closely inspected when they are 6 to 12 weeks old. Introduced cattle should be examined closely when they have been in the area for 3 to 8 weeks.

In areas where Theileria spp. is normally not present — but cattle from Theileria spp. infected areas have been introduced — home-bread cattle should be checked regularly between 2 and 6 months after the introductions.

General management

Cattle in good condition and on good feed will be less susceptible to benign theileriosis. Careful attention should be given to nutrition, parasite control and trace element supplementation (if required) to minimise susceptibility to disease.

If possible, mustering or otherwise stressing stock should be avoided at times when there is a high risk of disease.

It is not presently known if infection can be transferred from animal to animal by management procedures such as multiuse needles and castration knives.

If practicable, items such as castration knives should be cleaned and then disinfected between animals. Where this is not possible, such as vaccinating a mob of cattle, sharp needles should be used and changed regularly to minimise blood transfer.

Tick control

Reducing tick numbers using a registered acaricide should reduce the likelihood of cattle becoming infected. Although suppression of tick numbers will not do anything for animals already infected, it may reduce new instances of transmission.

It is highly unlikely that bush ticks from a property can be eradicated as they spend more than 9 months living on the ground and can attach to other animal hosts such as wildlife. A nil tick population through chemical treatment should therefore not be the aim of any tick control program.

Where a producer is experiencing severe problems with benign theileriosis, a more intensive acaricide regime may be unavoidable. Cattle will require treatment every 2 to 3 weeks for a few months during summer and autumn. It must also be noted that frequent usage of acaricides may engender chemical resistance in the tick population and will adversely affect livestock product marketing due to the lengthy withholding periods applicable. All aspects of tick control must be discussed in detail with livestock owners prior to implementing a control program.

It is important to note that on some properties, benign theileriosis has occurred where no bush ticks have been seen on cattle, and the actual mode of spread on all properties has not been determined. It is suspected that other vectors or methods of spread could be involved.

Rotational grazing practices may also help to control ticks — the use of non-bovine species may assist with removal of ticks from pasture prior to the introduction of cattle.

Other forms of theileriosis exotic to Australia

Other forms of theileriosis exotic to Australia exist and include:

- benign African theileriosis (T. mutans)

- tropical theileriosis (T. annulata) in Africa, southern Europe and Asia

- East Coast fever (T. parva), a highly pathogenic form of theileriosis occurring in Africa.

Most of these infections occur in cattle, although some affect sheep and goats.

More information

For further information contact the our Customer Call Centre on 136 186.