Blackheaded pasture cockchafer

The blackheaded pasture cockchafer (Aphodius tasmaniae), is a native insect of south-eastern Australia including Tasmania. In Victoria, blackheaded pasture cockchafers are mainly active in the Western District, the Southern Wimmera, the North-Central and Central districts, the North-East and Gippsland.

They have become an important pest of improved pastures, lawns, golf courses and parks and appear to prefer areas where the annual rainfall exceeds about 480mm.

Description

The adult cockchafer beetles are dark brown to black in colour, have long fine legs and are approximately 10 to 11mm long (Figure 1).

The adult cockchafer beetles are dark brown to black in colour, have long fine legs and are approximately 10 to 11mm long (Figure 1).

The cockchafer larvae (grubs) are white or greyish-white in colour with dark heads and soft bodies (Figure 2). The larvae tend to curl into a C-shape upon exposure or when handled, hence they are often referred to as 'curl' grubs. Their gut contents can often be seen through the external covering in the medium to larger larvae. Fully grown larvae are 15 to 20mm long.

Feeding damage

The cockchafer grubs feed on humus in the soil until the autumn rains soften the ground and promote pasture growth and they then tunnel to the surface for surface feeding from this stage onwards. They come out at night, often in response to a heavy dew or rain, to collect fresh pasture leaves which they drag into their tunnels for later consumption during the day.

The blackheaded pasture cockchafer grubs feed on clovers, ryegrass and animal dung and have been known to consume young wheat crops.

Paddock indications of blackheaded pasture cockchafer damage

Their presence may be noted by small mounds of soil around their tunnel entrances (Figure 3).  The larvae, and the damage they cause, gradually spreads out until the areas of infestation and the improved pasture species can seemingly start to 'disappear' very quickly. Broad-leaved or tap-rooted weeds and unimproved pasture species, such as bent grass, are left behind in the denuded areas (Figure 4).

The larvae, and the damage they cause, gradually spreads out until the areas of infestation and the improved pasture species can seemingly start to 'disappear' very quickly. Broad-leaved or tap-rooted weeds and unimproved pasture species, such as bent grass, are left behind in the denuded areas (Figure 4).

In April to May, the very young cockchafers are found nearer the centre of the damaged area, while the more mature larvae are on the outside. In late winter, the fully fed ones stay behind while younger larvae continue to advance. Maximum larval feeding occurs in winter when the rate of pasture growth is slowing down due to the cold weather. Bare patches usually become very noticeable at this time.

Blackheaded pasture cockchafer may constitute a minor problem in years with good rains when pasture is more plentiful but, in a drier season, when feed is short, this loss of pasture is problematical.

rains when pasture is more plentiful but, in a drier season, when feed is short, this loss of pasture is problematical.

Soil types most affected

Blackheaded pasture cockchafer infestations can occur in a wide range of soils varying from sandy loams to light clay loams. They do not thrive in either very sandy or very heavy clay soils and their numbers are greatly reduced in saturated soils. The colour of the soil has no affect on their presence.

Life-cycle and growth habits

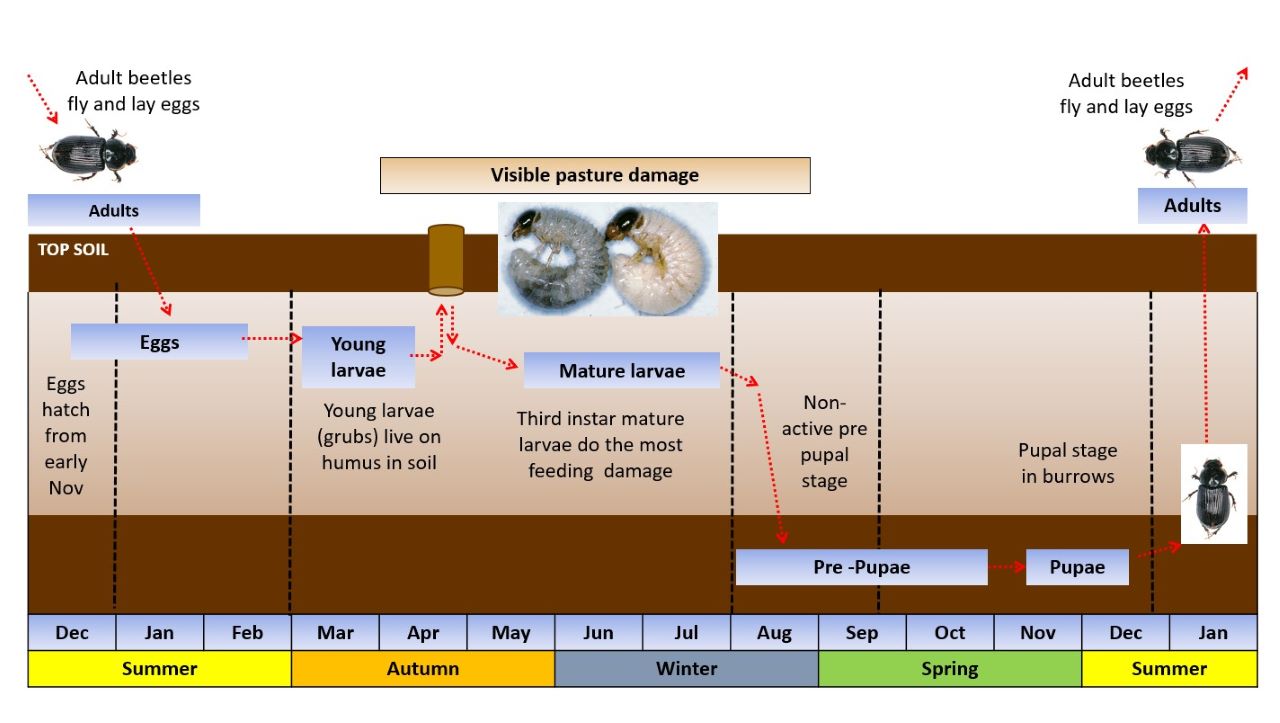

The blackheaded pasture cockchafer has a one-year life cycle (Figure 5). They emerge from the ground and fly at dusk on calm, mild evenings during January and February. They are often attracted to lights at night during this time. They may also be noticeable when large numbers of them burrow into animal manure, often pulverising and burying it.

The females are seemingly attracted to sparse pastures caused by heavy grazing and hay cutting for egg laying. They burrow about 10cm into the soil to lay their yellow oval-shaped eggs of about 1mm in diameter in batches of two to three dozen. These hatch into small grey coloured larvae or 'grubs' of 5 to 8mm in length after 18 to 21 days. Their head capsules are pale at birth but turn to shiny dark brown to black after a few hours.

The young grubs feed on the humus underground until the autumn break. They then tunnel to the surface and emerge at night to feed on the pasture, throwing up small mounds of soil around their outlets. The grubs grow through three stages or instars, digging deeper burrows and consuming more pasture throughout autumn and winter. Their tunnels may reach about 15cm in depth depending on the grub size of and soil hardness.

From July onwards, the grubs mature during feeding and turn progressively a more creamy-yellow colour as they accumulate fat reserves necessary for pupation. They usually continue to feed until they enter a non-active prepupal stage in late August before eventually pupating in their burrows in December. The white coloured pupae, approximately 10mm in length emerge as beetles the following January or February to continue the cycle.

Control

Unlike the redheaded pasture cockchafer, the blackheaded pasture cockchafer can be controlled by insecticides as they are surface feeders. Maintaining pasture cover over summer may reduce infestations but there are currently no other control options available.Pasture renovation may be necessary in some years.

Chemical control

To determine if control is needed, use a square mouthed spade and dig several holes to about 200mm depth about every 20 paces across suspect paddocks. Use the spade width to determine width and length of the hole. Treatment is likely to be needed if the average number of larvae per hole exceeds 5 to 6.

The grubs tend not to feed during dry warm or hot weather nor in cold or frosty conditions. Apply the appropriate insecticide, just before rain or when a heavy dew is expected ensuring to allow enough time (4 hours) for the spray to dry to prevent it being washed off the foliage. If this is not practical then apply it immediately after rain, once dry enough to prevent spray run-off. Consult local spray retailers or representatives for current recommendations and follow safety guidelines at all times.

Applying insecticides in July or August when the grubs have become mature will rarely be successful, particularly if the grubs have visibly stopped feeding. They may feed longer if the winter is mild and the soil is warmer or drier than normal.

Chemical control is often one of the methods available for plant pests as part of an integrated pest management program. More information is available from:

- your local nursery

- cropping consultants

- chemical resellers

- the pesticide manufacturer.

For information on currently registered and or permitted chemicals, check the Australian Pesticide and Veterinary Medicine Authority (APVMA) website.

Always consult the label and Safety Data Sheet before using any chemical product.

Maintaining pasture cover in summer

Very short (2 to 3 cm) or open pastures are more attractive to egg-laying females of the blackheaded pasture cockchafer whilst the opposite is the case for the redheaded cockchafer females. Using the correct grazing management to ensure a cover of about 5cm height between manure clumps will also ensure a more dense pasture and increase its longevity to some extent. This may render this type of pasture less attractive for blackheaded pasture cockchafer egg laying but has not been scientifically proven as such.

Re-sowing with soil disturbance

Re-sowing by using equipment which churns the top 3 to 5 cm of soil, such as a roterra, appears to greatly reduce further cockchafer damage. This activity either damages the very vulnerable grubs and exposes them to flocks of birds and other predators thereby reducing their effects post-sowing.

Unfortunately, this leaves a soft seedbed which may lead to pugging, resulting in less dense pastures if the paddock is too wet when grazed. Also re-sowing a large area of the farm at this late stage will dramatically increase the grazing pressure on the remainder of the farm, possibly requiring extra supplement to fill feed shortages.

Pasture recovery

In less severe infestations pastures may recover since their root systems are not attacked. If their regrowth is again attacked, then pasture recovery may be very slow and over-sowing or renovation may be required.

In severely infested paddocks, re-seeding will most likely be required to avoid germination too late into the cold period and to ensure some pasture growth in early to mid-winter. Ensure the grubs have been controlled (sprayed) to avoid new pastures being attacked again.

Which cockchafer is it?

Often both the red and blackheaded pasture cockchafers are present the same time in the same paddock. Wet weather or cattle trampling can mask the indicators of which cockchafer is causing damage. Table 1 indicates some ways to identify which of the two types of cockchafers are present.

Table 1: Differentiating between black and redheaded cockchafers

Blackheaded pasture cockchafer | Redheaded pasture cockchafer |

|---|---|

Head capsule is shiny brown to black within hours of hatching | Head capsule is red to reddish brown |

Tunnel visible with dirt mounds around the entrance | No tunnels visible |

Grubs move off quickly if handled or disturbed (approx. within a minute) | Tend to stay in 'C' shape for longer period if handled (for several minutes) |

Ryegrass and clover plants physically disappear from pasture | Ryegrass clumps appear dead but may be intermingled with green clumps |

Pastures become denuded (except for weed) in ever increasing areas | Clumps may be turned over by flock of birds or "pulling" by grazing animals |

Ground surface is covered with cockchafer castings, similar to worm castings around tunnel entrances | Ground may appear like talcum powder in dry weather with severe infestations |

Photo credits

Figure 1. Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment (Tasmania)

Figure 2. The South Australian Research and Development Institute (SARDI)

Figures 3-5. Agriculture Victoria

Reporting an unusual plant insect pest or disease

Report any unusual plant pest or disease immediately using our online reporting form or by calling the Exotic Plant Pest Hotline on 1800 084 881. Early reporting increases the chance of effective control and eradication.

Please take multiple good quality photos of the pests or damage to include in your report where possible, as this is essential for rapid pest and disease diagnosis and response.

Your report will be responded to by an experienced staff member, who may seek more information about the detection and explain next steps.

Report online