Redlegged earth mite

The redlegged earth mite (RLEM) (Halotydeus destructor) is a major pest of broadleaf crops and pastures in regions of Australia with cool wet winters and hot dry summers. The RLEM was accidentally introduced into Australia from the Cape region of South Africa in the early 1900s.

These mites are commonly controlled using pesticides. However, non-chemical options are becoming increasingly important due to evidence of resistance and concern about long-term sustainability.

Description

Adult RLEMs are 1 mm in length and 0.6 mm wide (the size of a pin head), with 8 red-orange legs and a completely black velvety body (Figure 1). Newly hatched mites are pinkish-orange with 6 legs, are only 0.2 mm long and are not generally visible to the untrained eye. The larval stage is followed by 3 nymphal stages in which the mites have 8 legs and resemble the adult mite but are smaller and sexually undeveloped.

Other mite pests – in particular blue oat mites, Bryobia mites and Balaustium mites – are sometimes confused with RLEM in the field. Blue oat mites can be distinguished from RLEMs by their blue-black body and an oval orange/reddish mark on their back, while Balaustium mites have a rounded dark red-brown coloured body covered in short stout hairs and can grow to twice the adult size of the RLEM. Bryobia mites are smaller than RLEMs and have an oval shaped flattened dorsal body that is dark grey, pale orange or olive in colour.

Unlike other species that tend to feed singularly, RLEMs generally feed in large groups of up to 30 individuals.

Feeding damage

The RLEM is called an earth mite because it spends 90% of its time on the soil surface, rather than on the foliage of plants. The mites feed on the foliage for short periods and then move around before settling at another feeding site. Other mites are attracted to volatile compounds released from the damaged leaves, which results in feeding aggregations.

Typical mite damage appears as ‘silvering’ or ‘whitening’ of the attacked foliage (Figure 2). Mites use adapted mouthparts to lacerate the leaf tissue of plants and suck up the discharged sap. The resulting cell and cuticle damage promotes desiccation, retards photosynthesis and produces the characteristic silvering that is often mistaken as frost damage.

RLEMs are most damaging to newly establishing pastures and emerging crops, greatly reducing seedling survival and development. In years with a late ‘break of season’ or with late-sown crops and pastures, seedlings can emerge in the presence of established populations of the RLEM, which can cause significant damage and in severe cases, entire crops may need re-sowing following RLEM attack.

RLEM feeding reduces the productivity of established plants and has been found to be directly responsible for reduction in pasture palatability to livestock.

Hosts

RLEMs have a very broad host range, including canola, wheat, barley, oats, lupins, sunflower, faba beans, field peas, poppies, lucerne and vetch, as well as pasture legumes and grasses. While RLEMs are less of a concern in cereal crops and in some pulses, they can cause some economic damage in some years. RLEMs also feed on a range of weed species including Paterson’s curse, skeleton weed, variegated thistle and capeweed.

Life cycle

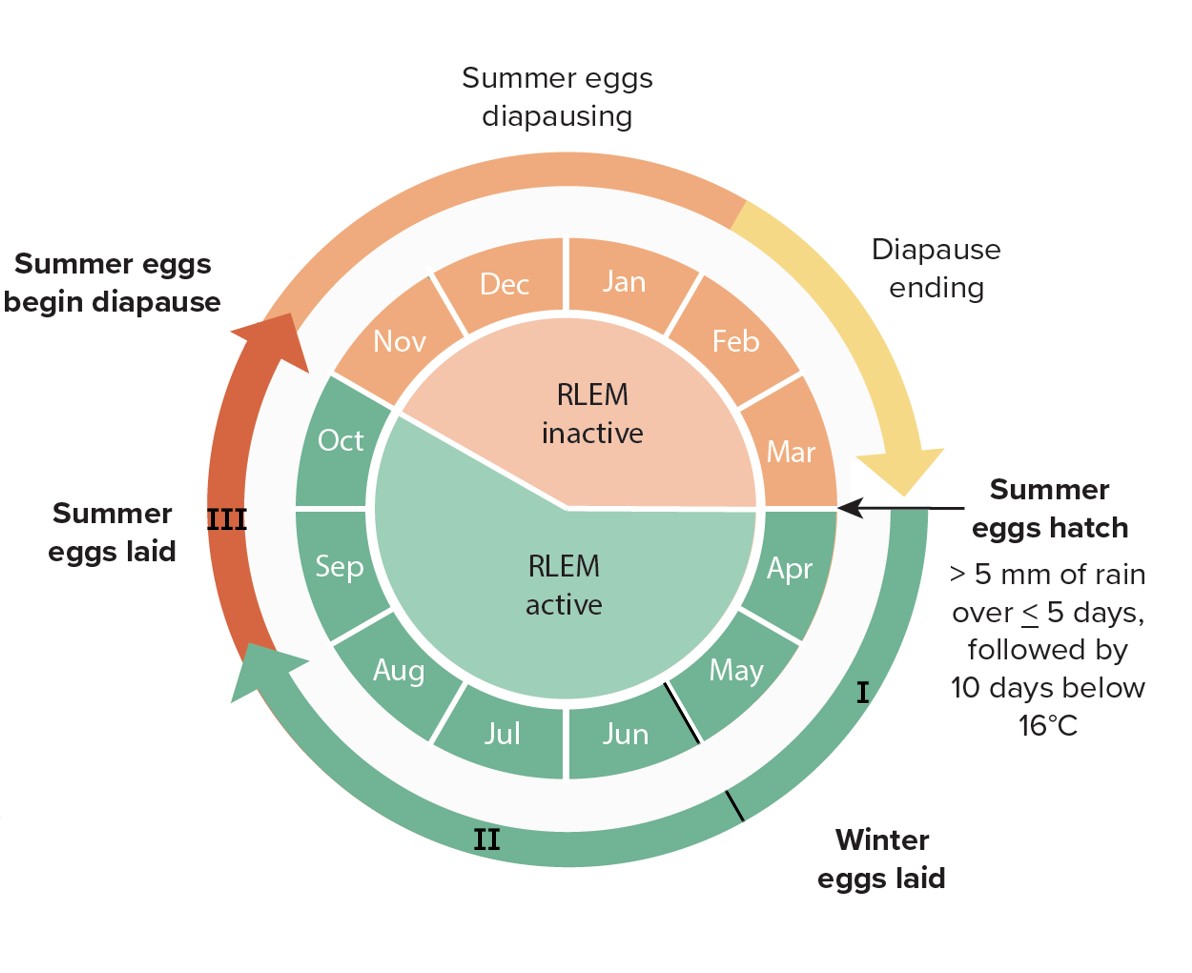

RLEMs are active in the cool, wet part of the year, usually between April and November. During this period, they may pass through up to 4 generations, with each generation surviving 6 to 8 weeks.

RLEM eggs hatch in autumn following exposure to cooler temperatures and adequate rainfall (Figure 3). It takes approximately 2 weeks of exposure to favourable conditions for over-summering eggs to hatch. This releases swarms of mites, which attack delicate crop seedlings and emerging pasture plants.

RLEM eggs laid during the winter–spring period are orange in colour and about 0.1 mm in length. They are laid singly on the underside of leaves, the bases of host plants (particularly stems) and on nearby debris. They are often found in large numbers clustered together. Female RLEMs can produce up to 100 winter eggs, which usually hatch in 8 to 10 days, depending on conditions.

Towards the end of spring, physiological changes in the plant, the hot dry weather and changes in light conditions combine to induce the production of over-summering or ‘diapause’ eggs. These are stress-resistant eggs that are retained in the dead female bodies. Diapause eggs can successfully withstand the heat and desiccation of summer and give rise to the autumn generation the following year.

RLEMs reproduce sexually, with an adult sex ratio that is female biased. Reproduction occurs when the male RLEM (which is smaller than the female) produces webbing, usually on the surface of the soil. It then deposits spermatophores on the threads of this webbing, which the female mite picks up to fertilise her eggs.

Distribution and spread

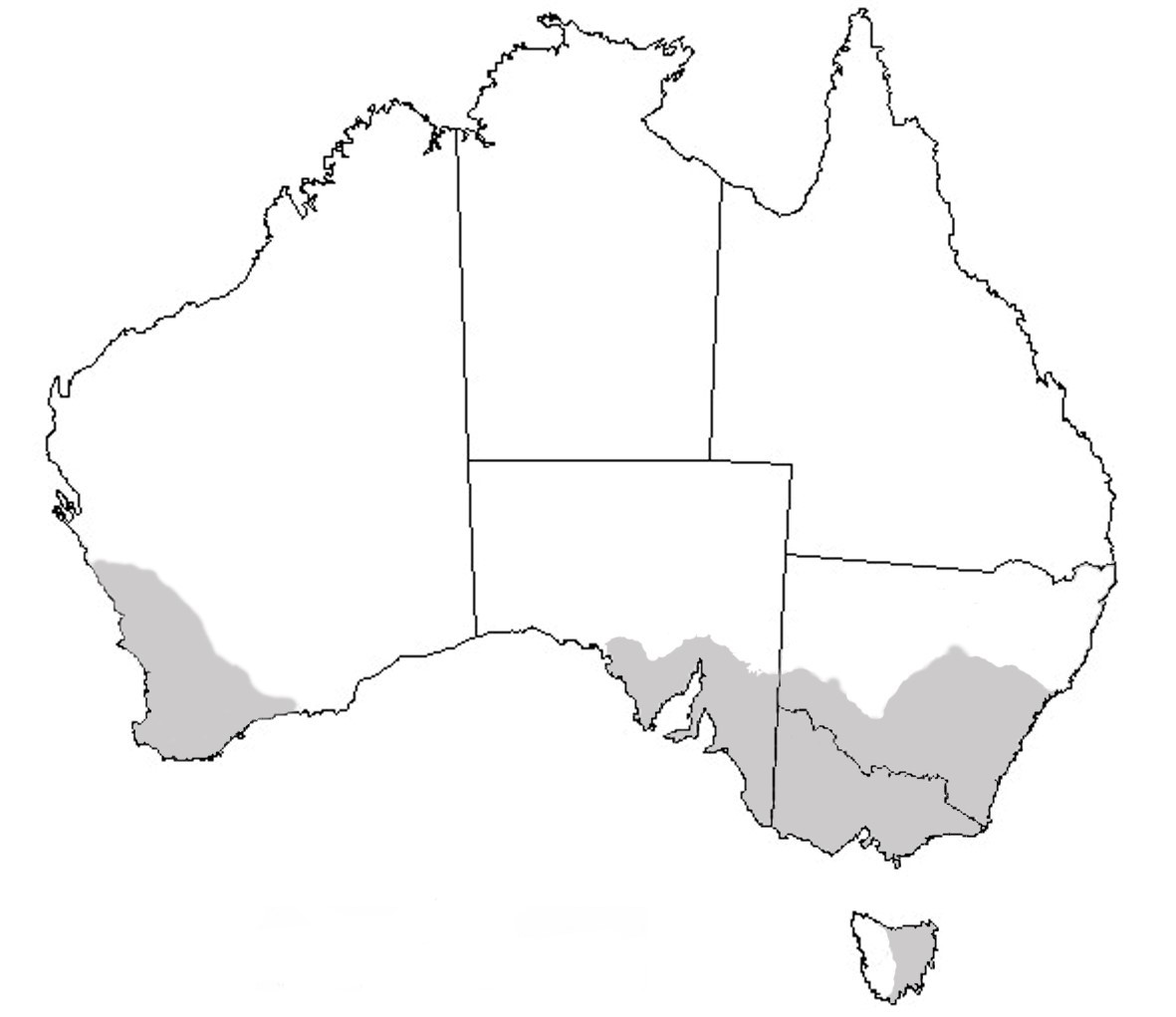

The RLEM is widespread throughout most agricultural regions of southern Australia. They are found in southern New South Wales, on the east coast of Tasmania, the south-east of South Australia, the south-west of Western Australia and throughout Victoria (Figure 4).

Genetic studies have found high levels of gene flow and migration within Australia. Individual adult RLEMs only move short distances between plants in winter, while long-range dispersal occurs via the movement of eggs in soil adhering to livestock and farm machinery or through the transportation of fodder and plant material. Movement also occurs during summer when over-summering eggs are dispersed by wind.

Monitoring

Carefully inspect susceptible pastures and crops from autumn to spring for the presence of mites and evidence of damage. It is especially important to inspect crops regularly in the first 3 to 5 weeks after sowing, as this is when crops are most susceptible.

In spring, RLEMs are best detected feeding on the leaves in the morning or on overcast days. In the warmer part of the day, they tend to gather at the base of plants, sheltering in leaf sheaths and under debris. They will crawl into cracks in the ground to avoid heat and cold. When disturbed during feeding they will drop to the ground and seek shelter.

An effective way to sample mites is to use a standard petrol-powered garden blower/vacuum machine. Place a fine sieve or stocking over the end of the suction pipe to trap any mites vacuumed from plants and the soil surface. Place the contents onto a black tray, as this allows any mites that are present to be easily identified.

Economic thresholds

Crops can compensate for RLEM damage, highlighting the importance of applying thresholds prior to the use of insecticides. For example, canola and wheat are susceptible to feeding damage caused by RLEMs at early growth development stages. In contrast, both crops can tolerate damage at the later growth stages, Wheat tolerates and compensates for mite feeding damage to a larger extent than canola. For more information about economic thresholds for, visit the Cesar Australia RLEM PestNote.

Control

Chemical control

Chemicals are the most commonly used control option against earth mites. While a number of chemicals are registered for control of active RLEMs in pastures and crops, there are no currently registered pesticides that are effective against RLEM eggs. An increased reliance on chemical control for RLEMs has led to increased levels of insecticide resistance in the pest.

Resistance to synthetic pyrethroid and organophosphate chemicals has been detected in parts of Western Australia and South Australia, and organophosphate resistance has also been detected in Victoria. Growers and advisers are encouraged to download the Resistance Management Strategy for RLEM in Australian grains and pastures. It has been developed to help growers effectively control this pest, while at the same time minimising the selection pressure for further resistance evolution.

For low to moderate mite populations, insecticide seed dressings are an effective method. Avoid prophylactic sprays; apply insecticides only if control is warranted and if you are sure of the mite identity.

Research has shown that one accurately timed spring spray of an appropriate insecticide can significantly reduce populations of RLEMs the following autumn. This approach works by killing mites before they start producing diapause eggs in mid-late spring. The optimum date can be predicted using climatic variables, and tools such as TIMERITE® can help farmers identify the optimum date for spraying. Spring RLEM sprays will generally not be effective against other pest mites and may exacerbate other mite problems, so caution is advised.

To minimise the risk of further resistance evolution in the RLEM, the selective rotation of insecticides with different modes of action is advised.

Chemical control is often one of the methods available for plant pests as part of an integrated pest management program. Consult your local nursery, cropping consultants, chemical resellers or pesticide manufacturer for advice that is suitable for your situation.

For information on currently registered and or permitted chemicals, check the Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority (APVMA) website. Always consult the label and safety data sheet before using any chemical product.

Biological control

At least 19 predators and one pathogen are known to attack the RLEM in eastern Australia. The introduced French Anystis mite can effectively suppress populations in pastures. Snout mites and other predatory mites are also effective natural enemies, along with small beetles, earwigs and spiders. Leaving shelterbelts or refuges between paddocks will help maintain natural enemy populations.

Natural enemies residing in windbreaks and roadside vegetation have been demonstrated to suppress the RLEM in adjacent pasture paddocks. When insecticides with residual activity are applied as border sprays to prevent mites moving into a crop or pasture, beneficial insect numbers may be inadvertently reduced, thereby protecting RLEM populations.

Cultural control

Using cultural control methods can decrease the need for chemical control. Rotating crops or pastures with non-host crops can reduce mite colonisation, reproduction and survival. For example, prior to planting a susceptible crop like canola, a paddock could be sown to cereals or lentils to help reduce the risk of RLEM population build-up.

Clean fallowing and controlling weeds, particularly broadleaf weeds like capeweed, pre- and post- sowing, can also act to reduce mite numbers as they provide important breeding sites for the RLEM. Where paddocks have a history of damaging, high-density RLEM populations, it is recommended that sowing pastures with a high-clover content be avoided.

Appropriate grazing management can reduce RLEM populations to below damaging thresholds. A shorter pasture with exposed soil will limit growth of mite populations. This can be an effective strategy in late spring as it reduces the amount of RLEMs producing over-summering diapause eggs. This results in less RLEMs hatching the following autumn.

Acknowledgements

This information was originally developed by Paul Umina from Cesar Australia and reviewed by Leo McGrane and Paul Umina in 2021. For more information on the work Cesar Australia is doing on the RLEM, visit the Cesar Australia website

Image credits

Figure 1: A. Weeks (Cesar Australia).

Figures 2, 3 and 4: P. Umina (Cesar Australia).

Reporting an unusual plant insect pest or disease

Report any unusual plant pest or disease immediately using our online reporting form or by calling the Exotic Plant Pest Hotline on 1800 084 881. Early reporting increases the chance of effective control and eradication.

Please take multiple good quality photos of the pests or damage to include in your report where possible, as this is essential for rapid pest and disease diagnosis and response.

Your report will be responded to by an experienced staff member, who may seek more information about the detection and explain next steps.

Report online