Blue oat mite

Blue oat mites (BOM) (Penthaleus spp.) are major agricultural pests of southern Australia and other parts of the world. They attack various pasture, vegetable and crop plants.

BOM were introduced from Europe and first recorded in New South Wales in 1921. Management of these mites in Australia has been complicated by the discovery that what was once considered a single species of mite is actually three distinct species each with different host preferences and pesticide tolerances.

Description

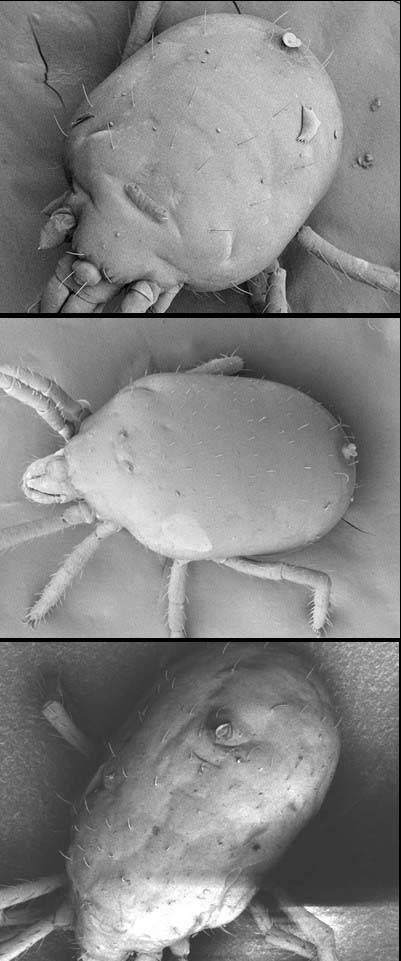

The three recognised pest species of BOM (Penthaleus major, P. falcatus, P. tectus) look very similar. Adults are 1 mm in length and approximately 0.7 mm to 0.8 mm wide, with 8 red-orange coloured legs. They have a blue-black coloured body with a characteristic red mark on their back (Figure 1).

On hatching, BOM are pink-orange in colour, soon becoming brownish and then green, before reaching the adult stage. Larvae are approximately 0.3mm long, are oval in shape and have 6 legs.

Distinguishing between the BOM species in the field is very difficult because a microscope is needed to see the morphological traits which separate each species. The main difference between species is the length and number of setae (bristle or hair-like structures) on the back of the mite.

- Penthaleus major has long setae arranged in 4 to 5 longitudinal rows (Figure 2a).

- Penthaleus falcatus has a higher number of short setae scattered irregularly (Figure 2b).

- Penthaleus tectus has setae of medium length and number (Figure 2c).

Confusion with redlegged earth mite and other mite pests

BOM are often misidentified as redlegged earth mites in the field, which has meant that the damage caused by BOM has been under-represented.

Redlegged earth mites can be distinguished from BOM by their completely black-coloured bodies and the tendency to feed in larger groups of up to 30 individuals. BOM are usually found singularly or in very small groups.

BOM can also be confused with other earth mite pests such as Balaustium mites and Bryobia mites.

Feeding damage

BOM spend the majority of their time on the soil surface, rather than on the foliage of plants. They are most active during the cooler parts of the day, tending to feed in the mornings and in cloudy weather. They seek protection during the warmer part of the day on moist soil surfaces or under foliage, and may even dig into the soil under extreme conditions. Typical mite damage appears as 'silvering' or 'whitening' of the attacked foliage (Figure 3). Distortion or shrivelling can occur in severe infestations. Mites use adapted mouthparts to cut the leaf tissue of plants and suck up the discharged sap.

BOM are most damaging to newly establishing pastures and emerging crops, greatly reducing seedling survival and retarding development.

Young mites prefer to feed on the sheath leaves or tender shoots near the soil surface, while adults feed on more mature plant tissues. BOM feeding affects the productivity of established plants and is directly responsible for reductions in pasture palatability to livestock. Even in established pastures, damage from large infestations may significantly affect productivity.

The impact of mite damage is increased when plants are under stress from adverse conditions such as prolonged dry weather or waterlogged soils. Ideal growing conditions for seedlings enable plants to tolerate higher numbers of mites.

Hosts

BOM attack a variety of agriculturally important plants, including cereals, grasses, canola, field peas and legumes (Table 1). They also attack many weeds, including Paterson’s curse, bristly ox-tongue, smooth cat’s-ear and capeweed.

There are differences in the plant types attacked by the three BOM species:

- P. major mostly feeds on pastures cereals and pulses.

- P. falcatus mostly attacks canola and broad-leaved weeds.

- P. tectus prefers cereals but can also be found on pastures and some pulses.

These preferences can be used as an indication of the species present in a particular paddock, but confirmation by an expert is recommended.

Table 1: List of agriculturally important crops attacked by blue oat mites in Australia

Species | P. major | P. falcatus | P. tectus |

|---|---|---|---|

Pasture | commonly attacked | occasionally attacked | occasionally attacked |

Cereals | commonly attacked | occasionally attacked | commonly attacked |

Canola | rarely attacked | commonly attacked | rarely attacked |

Lucerne | occasionally attacked | rarely attacked | occasionally attacked |

Lentils | occasionally attacked | rarely attacked | occasionally attacked |

Peas | occasionally attacked | occasionally attacked | rarely attacked |

Biology and life-cycle

BOM are active in the cool, wet part of the year, usually between April and late October. During this time they pass through 2 or 3 generations, with each generation lasting 8 to 10 weeks.

They spend the remaining months protected as 'diapause' or over-summering eggs which are resistant to the heat and desiccation of summer. These hatch in autumn after cool temperatures and adequate rainfall, when conditions are optimal for mite survival. Swarms of mites may then attack emerging crop and pasture seedlings.

Female mites deposit eggs either singly or in clusters of 3 to 6 on the leaves, stems and roots of food plants or on the soil surface. Those on the leaves are usually fastened by a slimy substance which is secreted next to and on the stem of plants.

Unlike many agricultural pests in Australia, BOM reproduce asexually. This mode of reproduction results in populations made up of female 'clones' which can respond differently to environmental and chemical conditions.

Having 3 pest species of BOM in Australia complicates control given the species differ in their distribution, pesticide tolerance and crop plant preferences. Despite these differences, all BOM species are typically treated identically in terms of control. This is a concern as management strategies against one species may not be as effective against another. Eradication of one species may result in another BOM species becoming more abundant.

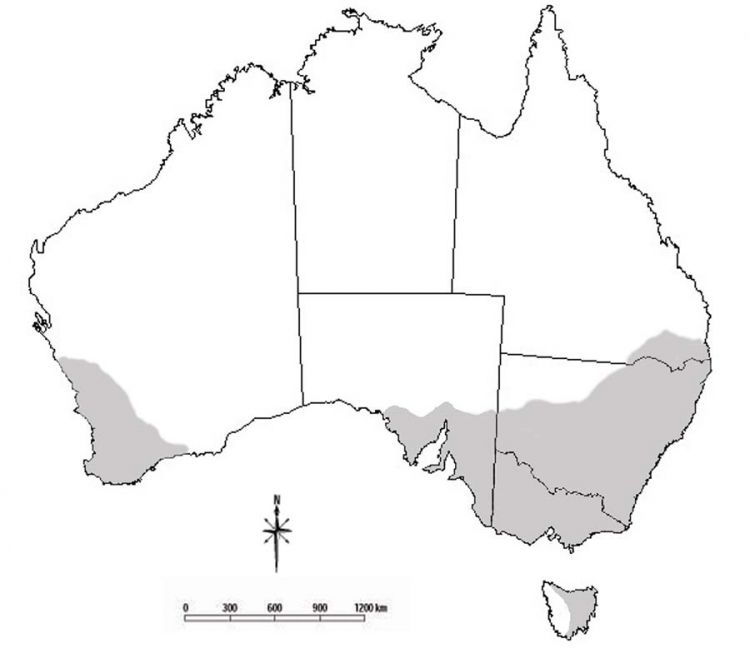

Distribution

BOM are widespread throughout most agricultural regions of Australia with a Mediterranean-type climate (Figure 2). BOM are one of the most important pest mites in cropping and pastoral areas of Victoria, New South Wales and Tasmania. They are also regarded a pest in southern Queensland, south-east South Australia and south-west Western Australia.

Spread

During winter, individual adult BOM move between plants over distances of several metres. Long range dispersal is thought to occur via movement of eggs carried on soil stuck to livestock and farm machinery, and through the transportation of plant material. Movement also occurs during summer when diapause eggs are blown by winds.

Monitoring

Carefully inspect susceptible pastures and broad-acre crops from autumn to spring for the presence of mites and evidence of damage. It is especially important to inspect crops regularly in the first 3 to 5 weeks after sowing. If mites are not observed on plant material, inspect the soil for mites.

Mites are best detected feeding on the leaves in the morning or on overcast days.

An effective way to sample mites is to use a standard petrol-powered garden blower/vacuum machine. Place a fine sieve or stocking over the end of the suction pipe to trap any mites vacuumed from plants and the soil surface. Place the contents onto a black tray, as this allows any mites present to be easily identified.

Control

Chemical control

Chemicals are the most common method of control against earth mites. Unfortunately, all currently registered pesticides are only effective against the active stages of mites; they do not kill mite eggs. While a number of chemicals are registered in pastures and crops, differences in tolerance levels between species complicates management of BOM. P. falcatus has a higher tolerance to a range of pesticides and this is often responsible for chemical control failures. P. major and P. tectus have lower tolerances to pesticides and are controlled more easily.

For low-moderate mite populations, insecticide seed dressings are an effective method. Avoid prophylactic sprays; apply insecticides only if control is warranted and if you are sure of the mite identity.

Chemical control is often one of the methods available for plant pests as part of an integrated pest management program. More information is available from your local nursery, cropping consultants, chemical resellers and the pesticide manufacturer.

For information on currently registered and or permitted chemicals, check the Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority (APVMA) website. Always consult the label and Safety Data Sheet before using any chemical product.

Biological control

Integrated pest management programs can complement current chemical control methods by introducing non-chemical options, such as promoting natural enemies of pests.

French Anystis mites can suppress populations of BOM in some pastures. Snout mites and other predatory mites are also effective natural enemies. Small beetles, spiders and ants can also play a role in controlling populations. Leaving shelterbelts or refuges between paddocks will help maintain natural enemy populations.

Preserving natural enemies when using chemicals is often difficult because the pesticides generally used are broad-spectrum and kill beneficial species as well as the pests. You can reduce the impact on natural enemies by using a pesticide which has the least impact and by minimising the number of applications.

Cultural control

Cultural controls such as rotating crops or pastures with non-host crops can reduce BOM colonisation, reproduction and survival, decreasing the need for chemical control.

- When P. major is the predominant species, canola is a potentially useful rotation crop, while pastures containing predominantly thick-bladed grasses should be monitored carefully and rotated with other crops.

- In situations where P. falcatus is the most abundant mite species, farmers can consider rotating crops with wheat, barley or lentils..

- For P. tectus, rotations that involve chickpeas or canola may be an effective means of reducing the impact of mites.

Many cultural control methods for BOM can also suppress other mite pests, such as redlegged earth mites. Many broad-leaved weeds provide an alternative food source, particularly for juvenile stages. As such, clean fallowing and the control of weeds within crops and around pasture perimeters, especially of capeweed and bristly ox-tongue, can help reduce BOM numbers.

Acknowledgements

This information note was originally developed by Paul Umina from Cesar Australia.

Photo credits

Figures 1 & 3: A. Weeks (Cesar Australia)

Figures 2 & 4: P. Umina (Cesar Australia)

Reporting an unusual plant insect pest or disease

Report any unusual plant pest or disease immediately using our online reporting form or by calling the Exotic Plant Pest Hotline on 1800 084 881. Early reporting increases the chance of effective control and eradication.

Please take multiple good quality photos of the pests or damage to include in your report where possible, as this is essential for rapid pest and disease diagnosis and response.

Your report will be responded to by an experienced staff member, who may seek more information about the detection and explain next steps.

Report online