Redheaded pasture cockchafer

In Victoria the redheaded cockchafer, Adoryphorus coulonii, is a common periodical pest of pasture in the south-west of Victoria, central Victoria and Gippsland.

Description

Adults

Adult beetles are squat, shiny and black to dark reddish-brown in colour. They grow to 10 to 15mm long and 8mm wide (Figure 1).

Juveniles

There are three juvenile (larval) stages.

Young larvae are approximately 4mm long with a soft white-grey coloured body.

Older larvae, known as cockchafer grubs, have six yellowish legs, a reddish-brown head capsule and a transparent body wall. They grow to around 30 mm in length and are all white except for the hind quarter which is a little swollen and more greyish in colour because of the ingestion of organic matter in the hind gut Cockchafer grubs are also known as white curl grubs form a C-shape upon exposure or when handled. (Figure 2).

Eggs

Eggs are white, 2mm in diameter, oval-shaped when newly laid but become more spherical with age.

Feeding damage

Unlike the blackheaded pasture cockchafer, Aphodius tasmaniae, which comes to the surface to feed on green pastures and clovers, the redheaded cockchafer grubs remain below the surface at all times. The grubs feed on organic and root material in the top 100mm of soil. When many larvae are present, pasture root systems are cut about 25mm below the soil surface. and the pasture can be easily rolled up like a carpet.

In the past, damage occurred every other year, because of the two-year life cycle of the cockchafer. Now extensive damage is occurring as a result of a build-up of overlapping populations. Damage can range from isolated patches to very large areas. Substantial losses start to occur when larval numbers exceed approximately 70 per square metre in March, and population numbers have been known to reach over 1000.

Low soil temperatures in winter slows down the larval activity but this resumes when the soil warms in late August with feeding continuing till early summer. The milder winter periods of latter years may not have reduced this activity as much as in the past.

The extent and severity of damage varies markedly from year to year and from property to property (Figure 3). Most damage becomes more obvious by May to early June. The main indication of their presence is most evident during a dry spell after the autumn break, when dead pasture is found among areas of green. Unlike the top feeding blackheaded cockchafer which has obvious tunnels, the redheaded cockchafers feed underground and remain below the surface so do not produce tunnels.

Clumps of dead and sometimes green pastures being pulled or uprooted by grazing animals and birds is another obvious sign. Large flocks of crows and ibis are good indications of the presence of a pest of some type and worth closer inspection. In severe dry periods the topsoil may even appear like a fine powder and very soft to walk on.

Often rain or stock traffic will remove signs which may have helped to pinpoint the culpable cockchafer such as tunnels used by the blackheaded pasture cockchafers. Use a shovel to dig to at least 20 cm depth in suspected areas of pasture to determine which species has caused the damage or if it’s a combination of both.

In wet autumns, damage from heavy infestations may not be apparent as the soil remains wet enough for the root-shortened pastures to survive and eventually recover, albeit in a much-weakened state. However, wetter pastures may also become much more easily pugged and vehicle traffic much more damaging.

Determining which cockchafer is causing the damage

Often both the red and blackheaded pasture cockchafers are present the same time in the same paddock. Wet weather or cattle trampling can mask the indicators of which cockchafer is causing damage. Table 1 indicates some ways to identify which of the two types of cockchafers are present.

Table 1. Differentiating between black and redheaded pasture cockchafers

Blackheaded pasture cockchafer | Redheaded pasture cockchafer |

|---|---|

Head capsule is shiny brown to black within hours of hatching | Head capsule is red to reddish brown |

Tunnel visible with dirt mounds around the entrance | No tunnels visible |

Grubs move off quickly if handled or disturbed (approx. within a minute) | Tend to stay in "C" shape for longer period if handled (for several minutes) |

Ryegrass and clover plants physically 'disappear' from pasture | Ryegrass clumps appear dead but may be intermingled with green clumps |

Pastures become denuded (except for weed) in ever increasing areas | Clumps may be turned over by flock of birds or 'pulling' by grazing animals |

Ground surface is covered with cockchafer castings, similar to worm castings around tunnel entrances | Ground may appear like talcum powder in dry weather with severe infestations |

Hosts

Pasture species that are shallow-rooted such as subterranean clover, Yorkshire fog, barley grass and annual and perennial ryegrasses are most susceptible to attack by redheaded pasture cockchafer larvae. Wheat has also been known to be stunted by this cockchafer. Deep-rooted plants such as lucerne, cocksfoot and phalaris, are less susceptible to damage.

To date, no endophyte has been identified which offers plant protection from the redheaded pasture cockchafer.

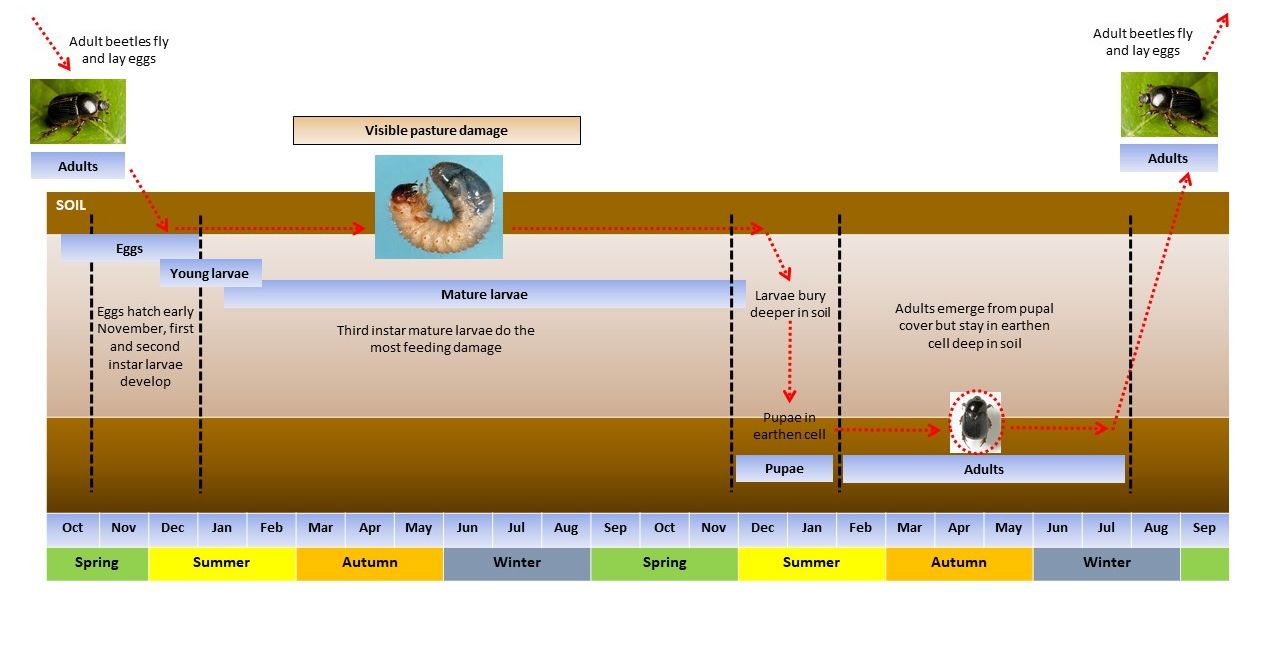

Life cycle

The redheaded cockchafer has a life cycle of 2 years, most of it spent underground (Figure 4). The adult beetles emerge from the soil at dusk from late winter to late spring and fly for a brief period before returning to the soil. Eggs are laid singly, or in loose dispersed groups of 10 to 20, at depths of up to 10 to 50mm in the soil under pastures. Areas of dense cover are preferred as this aids survival of young larvae during spring and summer.

Egg hatching occurs in late spring about 6 to 8 weeks after being laid. The first two larvae stages, called instars, also last 6 to 8 weeks. The larvae reach the third and final instar by early autumn and remain in this stage until summer.

All three larval stages feed on decaying organic matter, humus and plant roots in the soil but it’s the last stage which causes the most damage due to their feeding in autumn and winter.

At about one year of age the larvae change to a creamy colour and move deeper into the soil in December and January to pupate in earthen cells. The ginger brown pupal stage lasts 3 to 8 weeks. The adults (as beetles) then emerge from the pupal covering at the end of summer or early autumn but remain in the pupal cell for until August. They then dig their way to the surface to fly off and repeat the cycle. Dissections of the adult beetles have shown they do not feed.

Distribution

In addition to Victoria, the pest is found feeding on in pastures of the southern tablelands of New South Wales, the lower south-east region of South Australia and northern Tasmania.

It prefers areas where the annual rainfall is greater than 500mm but is only problematic in the drier years in these zones. The wetter seasons results in a substantial reduction in their population due to drowning, disease and being trampled by animals.

The pest tends to be more prolific on the lighter sandy loams and silty loam soils but have occasionally been found on clay loam soil in drought conditions.

Control

Chemical control

There are no known preventative management options and currently no insecticides registered for the control of redheaded pasture cockchafers. The underground feeding habit of the larvae gives them cover from insecticides.

Recovery options

Unfortunately, little research has investigated the recovery of pastures or techniques to re-establish pastures while the cockchafer is still active in the soil.

Re-sowing damaged pastures by direct drilling with perennial ryegrass can be disastrous as the newly established root systems of the new pastures will also be attacked. The new seedlings have little residual energy stored in their lower stems to aid recovery. These new plants may survive as weakened and sparser pastures prone to weed infestation or may often die.

If re-sowing is delayed till the cockchafer activity ceases, the prevailing cold conditions will lead to slow pasture establishment and delayed growth for several months.

The following suggestions are based on the anecdotal experience of farmers and contractors.

Re-sowing with soil disturbance

Re-sowing by using equipment which churns the top 3 to 5cm of soil, such as a Roterra, appears to greatly reduce further cockchafer damage. This activity either damages the very vulnerable grubs and/or exposes them to flocks of birds and other predators reducing their effects post-sowing.

Unfortunately, this leaves a soft seedbed which may lead to pugging, resulting in less dense pastures if the paddock is too wet when grazed. Also re-sowing a large area of the farm at this late stage will dramatically increase the grazing pressure on the remainder of the farm, requiring extra supplement to avoid overgrazing.

Consider also that after an extensive dry period, north-facing slopes tend to be more affected by the redheaded pasture cockchafers than south facing ones. It may be worthwhile re-sowing these particular paddocks, using a soil disturbing machine, in the year when damage is occurring rather than waiting until the following year.

In years of expected cockchafer damage (after long dry periods the previous year) consider leaving pastures in the north-facing paddocks short in late spring by either grazing them well or cutting them for silage.

Other species

New perennial ryegrass strains have been developed from plants selected from pastures undergoing drought and damage by redheaded pasture cockchafers. They have deeper rooting, are more tolerant of waterlogging and quicker to recover after summer.

Oats, but not wheat, may also be drilled into infested patches to replace missing green feed, as oat roots are seemingly not attacked by redheaded pasture cockchafer larvae.

Deeper and more fibrous rooting plants such as lucerne, cocksfoot and phalaris may be an option in some situations.

Rolling

Rolling damp, but not too wet, infested pastures can be of use by re-establishing contact of the truncated roots with the soil.

Pasture management

Redheaded pasture cockchafers seem to favour egg laying in longer pastures in spring for increased survival of its eggs and young larvae. Observations of heavier infestations have been noted in under grazed pastures compared to adjacent pastures which had been well grazed. It has been observed that a paddock cut early in spring for silage was not affected by cockchafer grubs but an adjacent paddock cut for late hay was badly affected the next autumn! In contrast, the blackheaded pasture cockchafer beetle favours short pastures for laying its eggs in summer. No research has verified either of these observations.

Pasture management should be based on principles of achieving maximum growth of high-quality pasture at all times of the year. This requires pastures to have 2.5 to 3 leaves before grazing and a grazing residual height of about 5cm between clumps after grazing.

Liming

Liming has been anecdotally linked to reduced cockchafer problems, although the results may due to long grass at beetle flying time and chance landing elsewhere. A short term plot trial, using slaked lime to speed up reaction time, gave no control at all. Research is needed to assess whether liming is a viable control technique.

Photo credits

Fig. 1. Photographer: Jon Augier Museums Victoria

Fig 2. Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment (Tasmania)

Fig. 3. The South Australian Research and Development Institute (SARDI)

Fig. 4. KJ Finlay, Agriculture Victoria

Reporting an unusual pest or disease of plants or honey bees

Report any unusual plant pest or disease immediately using our online reporting system or by calling the Exotic Plant Pest Hotline on 1 800 084 881. Early reporting increases the chance of effective control and eradication.

Please take good quality photos of the pests or damage to include in your report where possible, as this is essential for rapid pest and disease diagnosis and response. For tips on how to take a good photo, visit the Cesar Australia photo for identification guide.

Your report will be responded to by an experienced staff member who will seek information about the detection and explain next steps, which may include a site visit and sampling to confirm the pest or disease.

Report online