Australian plague locust – identification, biology and behaviour

About Australian plague locusts

The Australian plague locust (Chortoicetes terminifera) is the most economically important locust species found in Australia. In favourable weather conditions (high spring and summer rainfall), locusts can quickly multiply and form swarms.

If left unmanaged, swarms can migrate over large distances and cause severe damage to:

- pastures

- horticultural crops

- home gardens

- parks

- sporting grounds.

What is the difference between a grasshopper and a locust?

Grasshoppers and locusts behave differently. Grasshoppers are solitary, whereas locusts can become sociable and form swarms. Swarms of locusts have the ability to migrate long distances to find new food sources. Although other species of native grasshoppers in Victoria can be seen in large numbers, they rarely form coordinated aggregations.

Life cycle

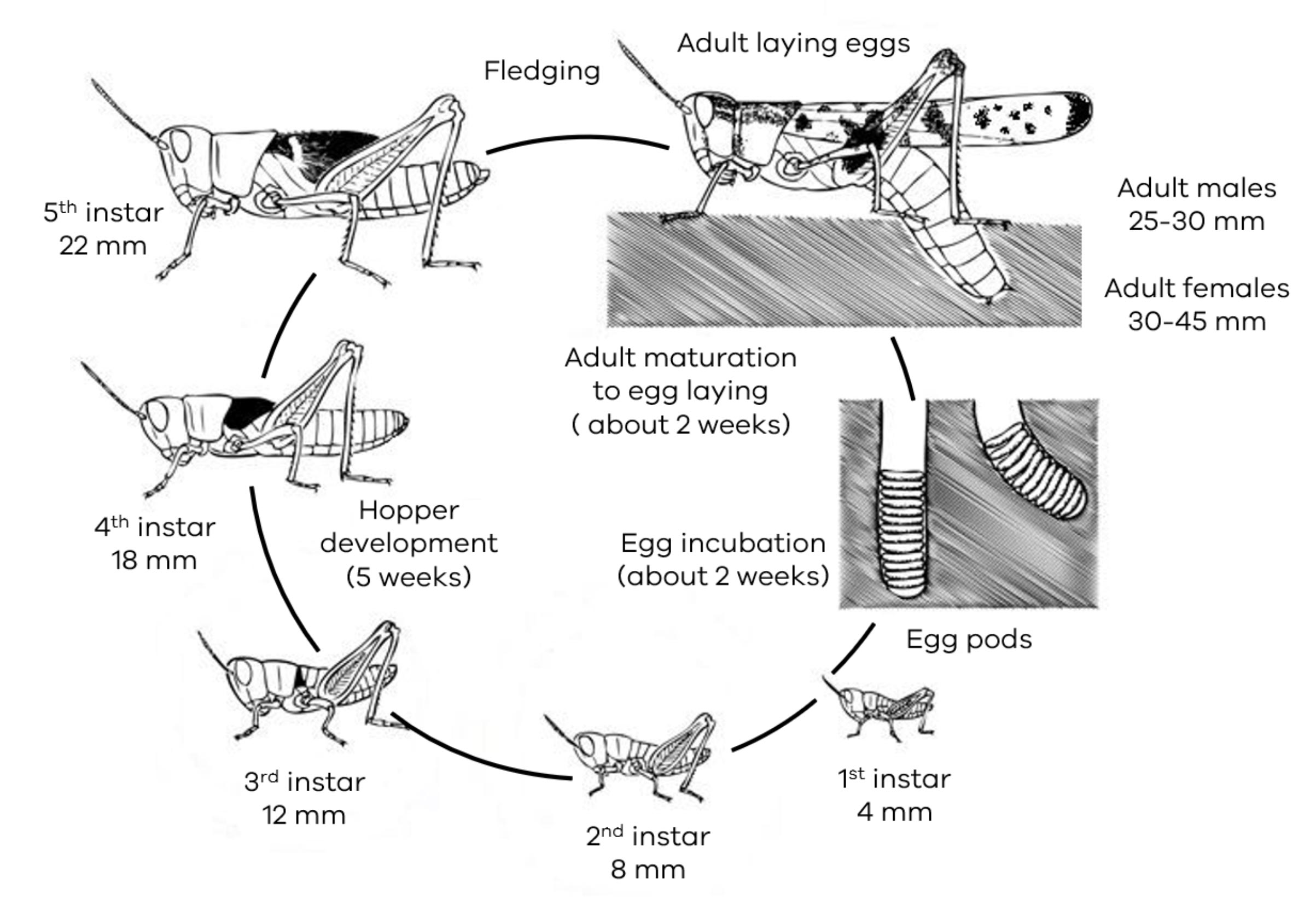

After hatching, locusts undergo five juvenile growth stages (instars) before reaching adulthood. Immature locusts are known as hoppers or nymphs. Locusts generally mature within two weeks of becoming adult, depending on weather and availability of food. Under optimum conditions, two to three generations of locusts can occur in one year.

Adults

Adult locusts can be identified by the large dark spot on the tip of their hind wing and their distinctive red-coloured hind legs (Figure 2). Their body colour varies between grey, brown and green (Figures 3, 4 and 5). Males are 25 to 30 mm long while females are 30 to 45 mm long.

Colour variation in Australian plague locusts

Egg laying

Female locusts lay their eggs 2–10 cm beneath the soil in pods, which contain 30–60 banana-shaped eggs (Figure 6). A single female locust can lay 2–3 pods during her lifetime. Each pod is sealed with a frothy plug that provides moisture and protection (Figure 6).

Egg-laying females will have their abdomen firmly planted in the ground (Figure 7). They are hard to disturb and don’t fly away when approached.

They are often in high densities in full sun and there is usually much low-level flight activity observed in the area as well.

Monitoring egg beds

Thousands of female locusts can crowd an area and lay eggs to form a mass laying site called an 'egg bed'. The ground where eggs have been laid looks like a sieve, with lots of shallow holes that are close together (Figure 8), although the holes although the holes can be are quickly covered by soil. Egg beds are hard to find unless you have previously witnessed an egg-laying event and usually involves digging up clods of soil to find the egg pods (Figure 9). It is useful to mark the location of previously known egg beds for future monitoring.

Female locusts will often drill test holes without laying any eggs to gauge the suitability of the soil, so the actual extent of an egg bed can be overestimated and become active.

Egg development

Eggs need warmth and moisture to incubate in the soil. Given sufficient moisture and a daily maximum of 35°C, egg development is completed in just over two weeks. With a daily maximum of 25°C, development can take over a month. Egg development does not take place below 15°C.

Hatching normally occurs from spring through to autumn, with two to three generations hatching through that period if conditions are favourable. Eggs laid in Victoria from late February to early March onwards usually become dormant until the following spring.

Eggs can hatch almost simultaneously in warm conditions, or over several weeks in cool, damp conditions.

Hoppers

After hatching, locusts undergo five juvenile stages (called ‘hoppers’ or ‘instars’) before reaching adulthood. First instar hoppers are approximately 4 mm long and are white in colour when they first hatch, but rapidly darken to pale brown, dark brown or black (Figure 10).

Thousands of young hoppers can emerge from an egg bed and remain in the location for several days before dispersing into surrounding vegetation.

As hoppers develop, they can form into aggregations called ‘bands’. Bands may extend over several kilometres, are often visible from the air and resemble a tide mark on the shore (Figure 11). Hoppers typically march in the same direction within the band. The front line of a band could hold between 1,000–5,000 hoppers per square metre. These bands are very destructive as hoppers can consume everything within their path.

The ideal time to spray hoppers is at the second or third instar stage (around two weeks after hatching) when band densities reach or exceed 80 hoppers per square metre. Once they develop wings and become more mobile, locusts are extremely hard to manage.

For more information, see Managing Australian plague locusts.

During mid-summer, hoppers can complete their development into a mature adult locust in 20–25 days.

Locust swarms

Adult locusts are gregarious, meaning they like to band together in large groups. When densities reach high levels, they can form clusters and take daytime flights of up to 20km, which usually occur in light winds (less than 3 m/sec) and at temperatures between 20°C and 35°C.

These swarms generally fly between 3 and 20m off the ground, appearing to roll across the countryside.

Large swarms occur when adult locusts are present in very large numbers. Swarms initially form in Queensland and northern New South Wales (NSW) and generally head south on hot northerly winds. These swarms usually land in central NSW where, given favourable conditions, can breed giving rise to new swarms which can fly south into the Riverina of NSW or into northern Victoria.

Successful breeding in the Riverina can result in swarms crossing the Murray River into Victoria in areas with less tree cover. This occurs in late spring, summer and predominantly autumn, infesting crops and pastures in northern Victoria. On occasion, locusts can invade southern Victoria.

Locust migration

Migratory flights of up to 800 km occur only at night, generally on strong, warm winds associated with fronts or low-pressure systems. Mass take-off after sunset usually only occurs when the surface temperature is above 20°C, with the locusts flying at heights of up to 1,000m.

Migration flight is usually, but not exclusively, to the south or south-east. Migration flights can cause locusts, in very large numbers, to appear literally overnight in new locations. Migration is important both in the origin of outbreaks and often, in their collapse, as it does not necessarily lead to locusts arriving in areas where there are conditions suitable for successful breeding. Previously, there have been reports where locust swarms overshot continental Australia and drowned in Bass Strait.

Locust damage

Locusts can be ravenous feeders of fresh, green plants and cause severe damage to pastures, horticultural crops, gardens, parks and sporting grounds, if unmanaged. Hoppers can form into larger aggregations known as ‘bands’ and can quickly damage pastures. Adult locusts can migrate over large distances and can devastate crops and pastures, in particular cereal and pulse crops. Often, a swarm will land during the night and will have eaten a crop or pasture by daylight the following morning.

Communities can also be impacted by locusts, with swarms damaging gardens, parks and sporting grounds, covering buildings and clogging car radiators.

For more information, see Information for households and gardeners.

Image credits

Figure 1, 6 & 8 Australian Plague Locust Commission (APLC)

Figure 2, 3, 4 & 7 Micheal Moerkerk, Agriculture Victoria, Horsham

Figure 5 & 10 Agriculture Victoria

Figure 9 Gerry Watt, Agriculture Victoria, Ballarat

Figure 11 Lyn Jacka, Agriculture Victoria, Mildura

Report locusts

Landholders are responsible for reporting and managing locusts on their land. If you see locusts or locust activity (egg laying, swarming), please notify Agriculture Victoria as soon as possible so that we can monitor locust populations and movement. Phone the Customer Contact Centre on 136 186 or report online:

Report Australian plague locusts